Cats, the internet, and you

The cat person’s home is insane. But don’t worry: so are you. The house is painted in cheery hues but it has the logic of a nightmare: a kitchen full of bookshelves leads into a bedroom full of end tables. Two beds sit in a back room, forming a right angle, behind which is a low-slung coffee table full of videogames and joysticks. There is nothing into which you might even plug them. The rooms themselves form a quadrangle—each leading into the next. There is no front door. There is no exit.

Accordingly, you are going just apeshit. You are bounding from a kitchen sink to a fancy table and you are sending your tiny paws soaring out in front of you. You are ruining everything in this candy-colored hell, an agent of pure destruction. You have goals. They are largely internal, and they are correlated exclusively to your ability to fuck the cat-person’s home up. The best bang for your buck is the bookcases, full of tiny identical green volumes—the cat person is a Zola fan—which with a swipe you can send soaring to the floor. So you do. A paw juts out and you watch them tumble to—a bed? There is a bed below this bookcase. So after clearing off the tiny green Zola volumes—along with a bunch of larger red books, some bookends, a couple of plates, and a framed photograph—you hop onto the bed, where the vast majority of them have landed, and then you meticulously knock them off. As each item hits the floor, you breath a sigh of relief. The score counts upward.

When you have adequately destroyed the cat person’s home, you hop into a box, and, with a flourish, magically reappear in some new, insane cat-person’s home.

///

One of the great joys of working from home is knowing everything about my cats. Behaviorally speaking, at least. I know, for example, that Batman, despite the good intentions of his name, is never active; that he is always fucking sleeping; that he will not beg for food from me under any circumstances but if my fiancee is around he will shriek like a goddamn spoiled boy-prince until he gets the dollop of wet food his tender little digestive tract demands. He will not so much as raise his eyes to meet mine if he is hungry, which says a lot about his disposition. I know, conversely, that if for some reason I have not risen from my bed at 8:30 a.m. CST Athena will saunter in and try to hold a meeting with me, right on the spot, in delicate little yips; that actually this meeting is a pretense for her to get the bedroom to herself, such that she might lick her whole body clean for an hour or two before coming back out to attack my ankles while I work; and that at around 2 p.m. she settles in for a nap, during which she is at her peak sleepiness-wise, and during which she expands slightly, hairs fluffing up, and, were I to rub her belly or the back of her neck, she would look up with heavy lids, barely sentient, and gingerly try to bite me, because—sleepiness be damned—she still yearns to kill. The fight has not left her. This brief moment of tenderness might be confused for affection were she not so quietly assertive in the remaining 23 hours of the day that I exist to exalt her. It is nice that she lets up on this attitude, if only briefly.

she still yearns to kill. The fight has not left her

I see them do everything; I smell their most heinous shits. When Batman is weirdly active in the morning, I know that this will not change his afternoon ritual of sleeping for seven hours in the TV room. When Athena is strangely pliant in the evening I know the secret cause: it is because during the day she started climbing our fragile bookshelves again, convinced that at a certain height she might become a larger animal, and so I locked her in the pantry for 20 minutes as a punishment, and when the timer went off, and I unlocked the door, she glared at me insouciantly from a roasting pan on the top shelf, utterly unimpressed by the punishment—but that deep down she is cowed, somewhat. In the evening hours later she might be—not quite affectionate, but tolerant, I suppose, of our presence. Newly receptive. It lasts an evening.

When people come over she will clean herself up and then stand right in the midst of the party. She will hop on a literal pedestal (I own a cat pedestal) and preen until everyone in the room has properly observed her. I love her, but I do not trust her.

///

Catlateral Damage began as a goof. Designer Chris Chung made a simple Flash game for a jam back in January 2014 and, the internet being what it is, and by which phrasing I mean “the internet being a whirlpool of rage and boredom into which all content about cats becomes super-charged and super-powered and worthy of money and time,” the game went viral almost immediately. Now this goof is a full game, and, blessedly, it has mostly remained a goof. The static apartment of the original game is now a randomly generated, anarchic suite of homes. You level up cat abilities, unlock cat types, and discover hidden cat activities, but mostly you just do exactly what you are supposed to do: You jump from thing to thing and knock things off of things. The game barely differentiates and you will adopt this attitude, too, blithely and near-brimming with antipathy.

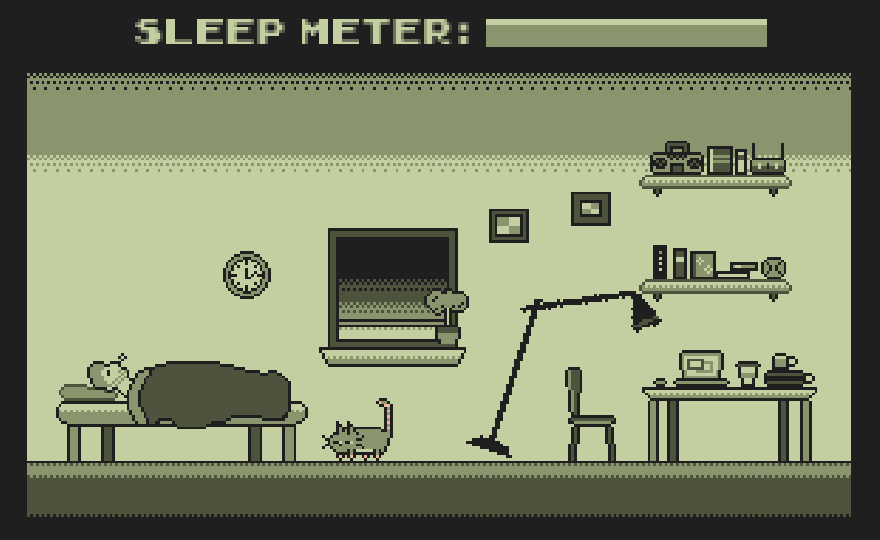

It enters, in 2015, a strangely crowded marketplace for cat-related videogames. The thematically similar My Garbage Cat Wakes Me Up at 3AM Every Day features a static, almost Game Boy-like look at a cat as it hops around a small bedroom, scratching and mewling until its owner wakes up. That title, obviously, carries a lot of weight here, thematically, but the result has the feel of a short film. Together with the grainy night-vision color palette, it feels punched out at, say, 3:30 a.m. in a fit of passive-aggressive fury. It makes no claims as to the nature of cats—only to the nature of its creator’s. And that nature is this: the cat is garbage.

Of course, nothing has quite dominated the cat-videogame landscape like Neko Atsume, the Japanese-language cat-feeding simulator that I will at the end of the year have to talk Kill Screen founder Jamin Warren down from unilaterally naming our game of the year. Jamin is not even a cat person, as far as I know. (When he slept on my couch once Athena quietly waged war on his feet, because she gives zero fucks about whether or not a houseguest is your boss.) Neko Atsume transcends the common delineations of “cat-person” or “dog-person,” or at least makes the experience of being a cat-person so compelling that it seemingly proves the notion that videogames are empathy machines. If you want to know how a cat person thinks about cats, in other words, play Neko Atsume.

Like the old virtual pets of yore—namely Tamagotchi, but also their descendents Nintendogs and Nintencats—Neko Atsume is about taking care of an animal by feeding it. One core difference is that here, there are dozens of animals relying on you. You are the proprietor of a sort of cat hotel, full of common and also quite fancy cats. Every few hours you check in and feed them more, and you are pleased to learn that they are still hungry. Let up your food-bringing duties, and the cats slink away when you aren’t looking. You buy toys to lure them back—the little structures and cotton knicknacks familiar to all cat owners—and watch the cats occasionally tussle with them or sit with great delight inside of them. Neko Atsume does not involve training the pets, or cleaning up after them, as many of its videogame predecessors did; it teaches you nothing beyond that if you regularly leave food in a dish outside eventually dozens of cats will show up, and shortly thereafter they will colonize your home, much like IRL feral cats. Eventually, in Neko Atsume, the cats will give you presents and start wearing costumes. They will become conquistadors and chefs and they will give you jewelry and baubles. IRL feral cats do not do this, which is why I do not feed them.

Still: by and large, the cats in Neko Atsume don’t do anything. They sit and eat. This is also the primary knock against cats as a species. Dogs, we cat people are told, love us! They go on jogs with us and welcome us home; they lick us! Cats, the internet and cat people everywhere proclaim, do not give a fuck. And this aloofness is supposedly their allure. Though Neko Atsume features a surprisingly complex cat-food economy, its cartoon kittens and looping, endlessly joyful waiting-room music reify the notion that cats are enjoyable because they do not care. It is the videogame version of ¯_(?)_/¯. The language barrier so many Western fans experience while playing the game only adds to the inscrutability, the uncrossable distance we all feel when a cat levels its alien eyes upon us.

///

There are a lot of cats on the internet. Google’s X Lab once hooked up 16,000 computer processors to create one gigantic mother-brain processor and fed it 10 million randomly selected YouTube thumbnails, and the first thing this super-machine learned was to recognize the face of a cat. This is to suggest that an artificial intelligence born inside of the internet might, when it first opened its mouth to speak, utter not “mother” or father,” but “meow.” Or at least “cat.”

Wikipedia, which is the closest thing we have to an internet brain in 2015, has a tortured relationship to cats. There is both a list of fictional cats in videogames and a list of cat videogames. Neither are particularly comprehensive, but they do help categorize the various types of feline experiences in games: the sort of meme-nodding Cats™ and Nyan cats, cuteness for cuteness’ sake, as epitomized by Mario et al. in cat suits; there are cats as assistants, as a sort of re-skin of videogame dogs, like those utilitarian, backflipping ones in Monster Hunter 4; there are occasionally cats that you are supposed to want to have sex with, like Felicia in Darkstalkers, a phenomenon which I will hereafter leave undiscussed; and, finally, the cat as biological creature, as pet, as thing that lives inside your home. Many of these cats are assholes—as in My Garbage Cat, and Catlateral Damage, but also a suite of unfortunate Garfield games—but many more just wander around, like those in Neko Atsume or No More Heroes. They are the mystery in the home, the unknowable roommate.

Literature, for its part, has explored this area more fully. There is a long connection between cats and the written word—or, that is to say, cat people and writers. How do you picture the proverbial cat person’s home, after all? Full of dusty, cherished tomes and dogeared poetry collections. Jack Kerouac, America’s Great Ramblin’ Bro, wrote, for example, in Big Sur, of showing up after a long trip and receiving the news from a friend that his cat had died. Kerouac’s writing is one long examination of home—where it is, who it is, what it represents—and here it is emblematized by a cat. Kerouac didn’t quite think it was manly to love a cat, but goddamn it, he loved that cat; it was the part of home he didn’t want to leave.

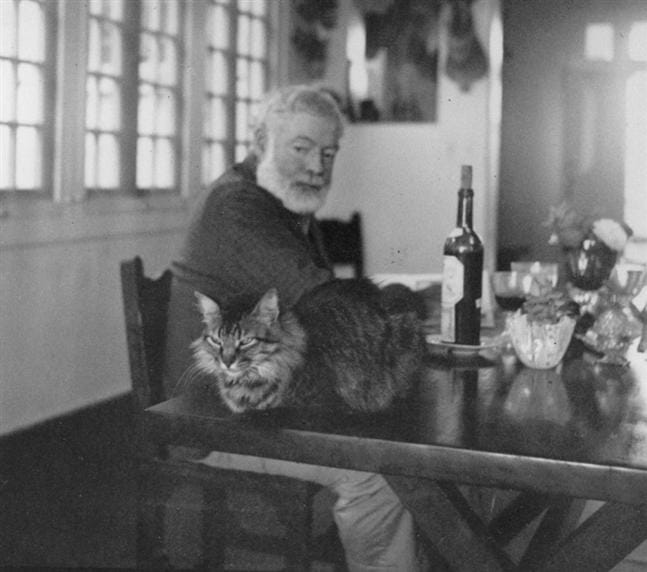

Hemingway also might be accused of a certain manly impassivity, but one of the more nakedly emotional passages I’ve ever read by him is about a cat. The author sometimes lived with dozens of cats, who have bred incestuously over the decades since his death and created a sort of impromptu farm of six-toed cats on his estate, leading to the purportedly widespread usage of the term “Hemingway cat” to describe any such feline with an extra toe. (For the record, I would call that cat a monster and stay away from it.) He called his cats “purr factories” and “love sponges,” both of which are probably not the first sequences of words I would use to describe cats, but his love for the animals is moving. To wit, this letter to a friend:

Dear Gianfranco:

Just after I finished writing you and was putting the letter in the envelope Mary came down from the Torre and said, ‘Something terrible has happened to Willie.’ I went out and found Willie with both his right legs broken: one at the hip, the other below the knee. A car must have run over him or somebody hit him with a club. He had come all the way home on the two feet of one side. It was a multiple compound fracture with much dirt in the wound and fragments protruding. But he purred and seemed sure that I could fix it.

I had René get a bowl of milk for him and René held him and caressed him and Willie was drinking the milk while I shot him through the head. I don’t think he could have suffered and the nerves had been crushed so his legs had not begun to really hurt. Monstruo wished to shoot him for me, but I could not delegate the responsibility or leave a chance of Will knowing anybody was killing him …

Have had to shoot people but never anyone I knew and loved for eleven years. Nor anyone that purred with two broken legs.

Hemingway struggled with depression and human connection throughout his life, but a cat’s quiet affection, the way its whole body could gently exude love, the way it might sit pleasantly on or nearby him, perhaps while he wrote—this was a small reassurance in the world.

Do a little digging on writing about cats and William S. Burroughs’ claim that they are “natural enemies of the state” pops up quickly. He dedicated a whole book, called The Cat Inside, to them. I have not read it, because my time on this earth is limited, but I’ve read some longer passages of it, and in one he gets at their more sublime qualities:

Evidence indicates that cats were first tamed in Egypt. The Egyptians stored grain, which attracted rodents, which attracted cats. (No evidence that such a thing happened with the Mayans, though a number of wild cats are native to the area.) I don’t think this is accurate. It is certainly not the whole story. Cats didn’t start as mousers. Weasels and snakes and dogs are more efficient as rodent-control agents. I postulate that cats started as psychic companions, as Familiars, and have never deviated from this function.

Burroughs was enchanted by their quiet, alien nature. Like the extraterrestrials he often spoke to and befriended while on DMT, cats were ambassadors from another realm. Edgar Allen Poe purportedly yearned to write “as mysterious as a cat”; Burroughs already sorta did, and in the animals he found spiritual kinship.

But maybe the most lovely literary evocation of a cat—the Neko Atsume of the written word—is by the early-twentieth century writer and avant-garde filmmaker Jean Cocteau. He was friends with Marcel Proust, Pablo Picasso, Yul Brynner, Kenneth Anger, Igor Stravinsky, and everyone else that mattered in art in the first half of the century. But he preferred the company of cats, despite everything; he founded something called the Cat Friends Club and pressed out adorable little badges for members. These badges are of a cat’s face. We should all make them sometime.

About the animals, he once said, “I love cats because I enjoy my home; and little by little, they become its visible soul.” One of the other things we really know about Jean Cocteau is that he also loved opium, which is perhaps not unrelated.

///

I’ve gotten off course. Cats are to me what lasers are to cats: I’ll follow them anywhere. Catlateral Damage came out a couple weeks ago and my attempts to review it have resulted in a lot of prolonged moments of petting Athena while she sits atop the fridge and peers through slitted lids down upon me—pitying, I believe, my inability to join her atop the fridge.

I am, in other words, inspired and delighted by Catlateral Damage, but I do not enjoy playing it. I have spent many hours reading about cats and playing The Witcher while Athena glares out of the window at nearby birds but, alas, these were hours not spent playing Catlateral Damage. Inspired by Jean Cocteau, I rolled a joint and decided to just play until I was done with the game. It has a couple of modes, but mostly it has Objective Mode, which is the one in which you are supposed to knock over a certain amount of things within a certain time limit. Both of these numbers are much higher than you’re thinking: say, 450 objects within 9 minutes. You sigh and get to work. The game’s sole reward is the ability to do this as different cats, which is strange, because these cats differ in cosmetics only, and you play the game from a first-person perspective. Thus the carrot dangled before you is the ability to imagine yourself as a different cat while bounding through a log cabin and knocking little books off the cat person’s shelves. Its sole narrative impetus is a snarky exclamation at the beginning of the level—”Those pesky humans took away my favorite toy! Those humans will pay”—coupled with the real-world impetus of crossing the next barrier (say, 10 consecutive levels completed). This lack of real driving purpose does not help the fact that the actual first-person hopping around that you’re in the game doing is not the most precise, or pleasant. First-person platforming is a meticulous sort of game design, and this is a clumsy, stupid cat, falling off the sink and backing ass-first off an end table in a way a real cat never would. The cats are hyperactive but idiotic, super-powered but clumsy; you always land on your toes but never where you want to.

I’ll note briefly that one objective is just “Play on a Caturday,” which is very cool.

But it’s hard to feel much “cat” in Catlateral Damage. The cat person’s home is—amiss. It’s no one’s home, a computer’s dream of a place. The term for this is procedural generation—the idea that the computer will craft endless levels, making a game that just spirals into infinity. I understand the promise of this idea, but I dislike it in practice. These bizarre nowheres feel like the Chicago of Watch Dogs, dreamed and unreal, faceless in their inventions; the assemblage of shelving units and knicknacks in Catlateral Damage feels like the people programmatically populating Watch Dogs, bankers who sniff glue and MMO gamers that just bought lottery tickets. The writer Ian Bogost has written of our culture’s blind faith in the power of the algorithm, saying it “gives us a distorted, theological view of computational action,” and calling the results “caricatures.” He’s speaking broadly, but this faith can have a particularly muddying effect on games, creating sprawl or clutter where there should be order and design. What’s more is that randomness is ugly; what we actually want is feigned randomness, randomness but with rules. The designers of No Man’s Sky—the poster-child for our new procedural universe—have spoken extensively of the problems of procedural generation. They’ve had to go back through their cosmos and author in order and artistry, make rocks clump together around trees in convincing ways. They’ve designed armies of drones to survey the wilds of their creation and then grade them on their impersonation of wildness.

// < ![CDATA[ (function(d, s, id) { var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "//connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.3"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs);}(document, 'script', 'facebook-jssdk')); // ]]>

There are worse ways to spend thirty seconds than watching a family of cats play in boxes. This is what cat heaven probably looks like. http://dify.me/1eA7CEZ

Posted by Distractify on Thursday, May 28, 2015

No Man’s Sky wants to magically generate a universe; Watch Dogs wants to make its city come to life; Catlateral Damage just wants more rooms for you to ruin. But a computer is no match for a cat. When scientists at Washington University recently mapped the genome of a house cat (named Cinnamon), they discovered shocking similarities with wild, undomesticated cats. The biggest difference between a housecat and a wild one is that the housecat is expecting food from a human, whereas the wild cat is not. The housecat still retains its predatory hearing, its appetite, its fundamental cat-ness. Compared to dogs, cats are vastly closer to their wild selves. Dogs and humans became friends a few millennia before cats and humans did, and, compounding that, it is suspected that cats have slowed their evolutionary domestication further by continuing to interbreed with wild cats. I cannot help but think of this as I gaze upon my cat collection in Neko Atsume.

Forget, then, that the cats of Catlateral Damage move like hopping Roombas—how could you procedurally generate a room for a cat? The very thing a cat brings to a room is a sense of wildness, of randomness, dictated by its own quiet pursuit of food and honor. That is what is infuriating about your garbage cat knocking things off a shelf: the room had order, and the cat disdained it. A cat lives in your home and abides by your rules, but the jungle is still in it. It has not given up the hunt. Athena thinks she’s taller than me because, in every way but one, she is.

///

And anyway, here is the thing about cats on the internet: it’s over. There is already a king. Maru is the greatest cat on the internet.

The enormous Scottish fold seems predisposed to fitting himself into strange spaces. There are videos of him leaping with immaculate comic timing into a tiny box, sliding from under a couch into a container, resting serendipitously in a sink. All cats may be mysterious, but Maru is surrounded by more mystery than normal. Nobody even knows the real name of his owner. A great Wired article went on a hunt for him and came up empty-handed; Maru’s owners worried that making the cat into a celebrity might disturb the very qualities that make him beloved. If you watch enough Maru—and I have watched very much Maru—you come to see that for all his dashing athleticism there is a quiet sincerity to his feline parkour. There is a sensitivity and earnestness to him that is as much Batman, plaintively turning his belly up in an unguarded moment, as Athena, sliding unbidden into my feet at 11 p.m. I want to be Maru’s friend in direct proportion to the amount that Maru probably does not need a friend at all.

The cat-person’s home in all the Maru videos is sublime, in the way that we dream homes in the Japanese countryside might be. It is very clean, both in its orderliness and in its tight, geometric architecture. It’s full of soft whites, sliding doors, meticulous pale wood floors. And while Maru is the star of all Maru videos, the cat-person’s home is an essential counterpoint, playing the straight man to the cat’s understated star. Many of the videos seem secretly recorded, perhaps by a webcam, and then edited together later. You get the sense that any video of Maru is actually a ten-hour recording of a home, a tightly ordered physical space into which the cat, sometimes with violence and sometimes with such benevolent imperiousness that he is literally asleep, injects wildness, variety, and life. An algorithm might be able to locate such an interaction on the internet, but it could not recreate it.