You’re not against free speech, are you?

This interpretive trap awaits anyone attempting to publicly wrangle the legacy of Charlie Hebdo. In late April, the PEN American Center announced that its literary gala would honor the French satirical newspaper. In response, a series of authors including Junot Díaz and Joyce Carol Oates penned a letter arguing that PEN missed the distinction between “staunchly supporting expression that violates the acceptable, and enthusiastically rewarding such expression.” This furore goes back to January 7th, when two gunmen open fired in Charlie Hebdo’s office. Twelve people died in the attack. A further eleven were injured.

Twelve people died in the attack. A further eleven were injured.

In the days and thinkpieces that followed, the discursive challenge posed by Charlie Hebdo became clear: Blanket condemnations of murder and rigorous defenses of free speech do not easily coexist with qualms some hold about the blunt instrument of Charlie Hebdo’s satire. So how do we talk about the important yet controversial institution that was—and is—Charlie Hebdo?

Save Charlie, a mobile game created by the French studio Cazap, is the latest entrant into this space. In one corner of its screen sits an isolated building, the home of a publication. From around the building emerge challengers, black penguin-like blobs. In promotional images, they appear to have horns. Your objective, as it is in all tower defense games, is to stop the attackers’ advances.

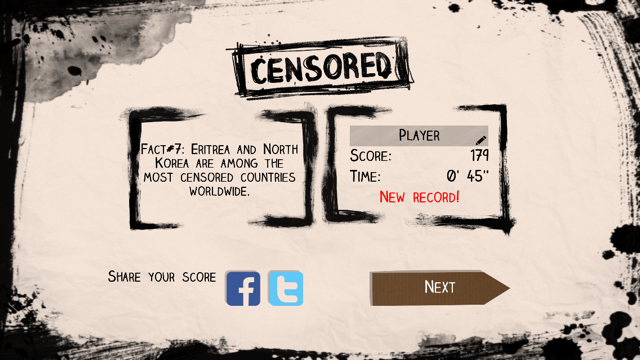

The twist in Save Charlie is that your weapons are those of a cartoonist. You can sling inkblots at your attackers or, in homage to whack-a-mole, hit them with newspapers. The message here isn’t subtle: The pen really is mightier than the sword. As they make it into your building, the invaders shutter windows. You lose when the publication has been completely shuttered. You are now censored. You have lost. A fact about press censorship is displayed alongside your high score.

Save Charlie, as the name indicates, is about Charlie Hebdo, but it isn’t really. You are nominally a cartoonist for Charlie Hebdo but the game has no real sense of place or context. It could be in Paris or somewhere else entirely. Likewise, its message about the importance of journalism is universal, or at least it should be, which is all well and good but suggests that the game has as much to do about press freedom in Eritrea as it does with a satirical newspaper in France. There is discordance between the platitudinous nature of Save Charlie’s gameplay and the very specific allusion in its title.

If language has failed many who attempted to discuss Charlie Hebdo, game mechanics might offer an alternate avenue. Games can present complicated power structures in a more digestible manner than a series of subordinate clauses. Save Charlie’s mechanics, however, decline the opportunity. The publication has an endless supply of weaponized inkblots and newspapers; the Visigoths at its gates also appear to be in endless supply. This makes for pleasant gameplay—so long as your fingers can keep up, Save Charlie will keep going—but says nothing about imbalances of power. Is your publication under attack by a totalitarian regime that has the power to close it entirely or a small band of homicidal maniacs who wish to deplete your ranks and scare you into closing shop? Save Charlie is so focused on its opposition to censorship that it never really bothers to truly conceptualize the different faces of censorship.

Save Charlie has no sense of place or context.

Save Charlie answers the easiest questions about Charlie Hebdo and press freedoms: free speech should be strongly defended and journalists should never be murdered. The game is comfortable when dealing in these absolutes but struggles mightily with grey areas. If inkblots are as strong a weapon as its moment-to-moment play suggests, might there not be occasions when a degree of restraint is called for? Save Charlie’s core mechanic occasionally contradicts the defence of Charlie Hebdo that it seems intent on making. Conversely, the suggestion that press freedom in states like North Korea can be established through the continual operation of printing presses is overwhelmingly simplistic. Save Charlie is a power fantasy about the role of an adversarial press that projects the plot of All the President’s Men onto every possible conflict between journalists and their detractors.

Cazap has announced that 50% of Save Charlie’s profits (the game offers in-app purchases) will be donated to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Whatever one thinks of Charlie Hebdo’s output this is a net positive: journalists across the world face serious challenges while carrying out important work. They deserve to be supported. They also deserve a game that truly attempts to engage with issues of journalistic ethics, freedom of speech, and structural power imbalances. Save Charlie is not that game. Its earnest didacticism is only of use when addressing low-hanging fruit. Instead of making you feel for the very real blood that has been spilled in defense of press freedom, Save Charlie makes you weep for all of the spilled ink.