Here’s a thing that happened to me once in Civilization IV: as the more-or-less benevolent emperor of Earth’s western hemisphere, I watched a hungry and growing China declare war on its vulnerable neighbor India. Chinese troops were pushing south into Indian territory, and the Indians were not going to be able to stop them. Trade suffered; the security of Arabia and even Europe was in doubt. I was much more technologically advanced than the Chinese; much richer; my home cities were an ocean away, untouchable. Western interests demanded intervention. The next turn I announced to the friend I was playing with that I was sending troops to Indochina.

“I don’t know if you should do that,” he said.

But I did. You know how this went. Sid Meier’s Civilization games are sometimes accused of being educational, but it’s not the three lines about how Stonehenge was built or the capsule description of the Malinese empire that educates you. It’s invading Vietnam. Many turns later, as “war weariness” immersed my major cities in paralytic riots and an endless procession of the world’s best-armed troops disembarked from Indian Ocean transports to die uselessly in a jungle stalemate, I realized I had learned something. More than the old chestnut about land wars in Asia–I had learned that an empire’s suicidal mistakes don’t just come from stupidity in its leaders or dementia in its body politic. They hide, like worms, in its “interests.”

Brave New World, the second expansion to Civ 4’s streamlined and sometimes dumber successor Civilization V, wants to make your interests more interesting than ever: to deeply complicate the dangerous tangle of deals, obligations, and suspicions. In focusing on international relations, Brave New World is nobly trying to improve not just Civ 5 but the entire Civ series, for which robust diplomacy is a kind of final frontier. A strategy game capable of generating interests so varied and complex naturally has trouble devising an interface for those interests to be bargained, traded, insisted upon, relinquished; all Civ diplomatic systems feel cramped even (especially) when inhabited by real human players. Many of Brave New World’s changes–political ideologies to complicate late-game relations; “tourism” to inspire simulated jealousy of other cultures; a “World Congress” where players can trade votes for this cause or that one–seem focused on relieving this cramp, on creating new ways for players to express themselves diplomatically.

The World Congress is Brave New World’s most obvious success, because the conflicting motives and pet causes of opposing delegates allow for real machination. If you want Ethiopian support for your resolution to institute a global army maintenance tax, but Haile Selasse doesn’t want to do it because he has like a dozen of those infuriating little guys with hats, maybe you should throw a delegate or three behind his own weird proposal to ban incense. Support for World Congress resolutions is now a tradeable item, like gold or bananas, in the diplomatic screen, and sometimes the effect is liberating: the feeling of suddenly articulating something you haven’t been able to talk about.

In focusing on international relations, Brave New World tries to improve not just Civ 5, but the entire series.

But because this is still a video game and you are still not actually George Washington, all you’re really talking about is numbers. World Congress resolutions are the global form of the “tenets” making up Brave New World’s ideologies and religions: the little bonuses, +10% to this and -15% to that, from which players sculpt their civilizations over the course of a game like they’re leveling up a WoW character. By the time the World Congress appears, then, getting a read on a player’s disposition, his concerns and priorities, only means looking at a list. Then you ally with civilizations whose lists look like yours, or bargain for changes to everybody’s list.

Civ games were not always so much like accounting. (They were still a lot like accounting.) Of course computers are only seeing arithmetic even when pretending to see something else, but Civ 5 pretends less: it plops colossal global variables at the top of your screen, telling you how many thousand “culture” or “faith” you have; it reduces its most exciting concepts to simple math.

Civ games were not always so much like accounting.

It’s exactly this reduction of a civilization’s strategic position to a collection of numbers and RPG-ish modifiers that makes features like the World Congress possible: when your interests are so neatly expressed, you can hash them out with other people even if the other people are robots. The less blocky flexibility of previous games–the ability to constantly adapt your civilization to circumstances, to switch from a democracy to a police state during a perilous war, to reinstate a monarchy at the drop of a blade, rather than just accruing bonuses–was both Civ 5’s biggest sacrifice and the obstacle that stood in the way of Brave New World’s biggest features. The expansion achieves things decades of Civ games have tried for, but it does it by reducing some of the game’s scope, and unmasking some of its uglier mechanics.

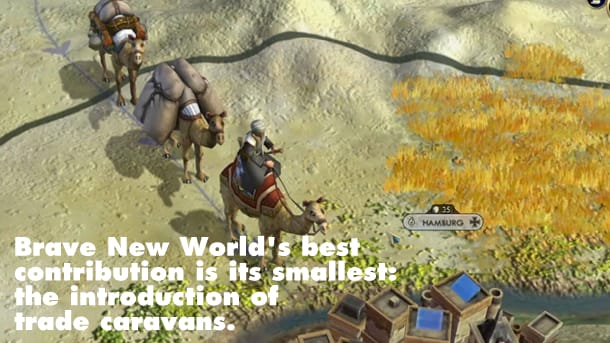

So old Civ fans, or players with spreadsheet fatigue, may find instead that Brave New World’s best contribution is its smallest: the introduction of trade caravans. They may be only a way to move gold-numbers and research-numbers between civilizations, but they’re physical objects, hampered by terrain and endangered by great distance; they can be blocked, plundered, killed, reassigned; they can soothe international relations or spark wars. Brave New World’s trade ledger represents what’s always been the best face of Civ: it entangles the crisp, abstract clarity of numbers and plans with the treacherous world of things-on-the-ground. From murky gaps like the one between your trade income and the actual physical circumstances of your caravans comes error, irony, hubris, self-destruction and fatal misperception. You know: history. Be careful.