Collecting Lives

The museum is the keeper of history and there is quite a lot of history to be kept. London is a city rich in history itself, and home to a diverse selection of museums and many many histories. On and around Exhibition Road, which could be considered the museum district, the Natural History Museum contains evidential and education artifacts of the diversity of life on Earth; the Science Museum hosts an assortment of objects representing man’s pursuits and progress in science and technology; and across the street, the Victoria and Albert Museum displays artwork from many disciplines spanning 2,000 years. Elsewhere the Imperial War Museum documents the history of British and Commonwealth conflicts, the National Portrait Gallery displays a vast collection of portraits, the British Film Institute archives and maintains a hundred years of motion-picture media, Pollock’s Toy Museum is something of a life-size dollhouse, and the Cartoon Museum holds more than 6,000 pieces of comic art.

Most literally with the fossils of extinct creatures, mummified remains of men, and reconstructed skeletons, the museum is where we keep our dead. This is and this isn’t as morbid as it sounds. Susan Stewart talks about the way that museums present “death and life, in that order.” The collections within are dead objects arrested in time, but arranged and documented in such a way that the audience can give them animation. The museum is a unique space where the memories of objects are turned into narratives and brought back to life. This is the profundity of Night at the Museum right here.

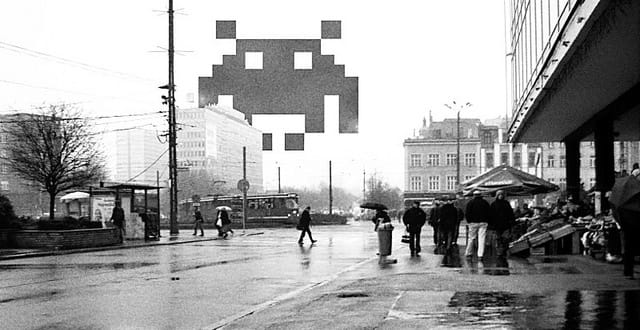

Computer games are substantial part of recent history, and have already acquired a massive amount of history in such a short time—not least because of generational evolution, but because the form spans so many disciplines, like technology, computing, art, music, play. But where do computer games go when they die?

For an entertainment media so young there has been so much death already. Consoles evolve, monitors too; computers RAM up, memories get built in, software goes from tape and cart to formatted discs and invisible data, we go online, genres develop, styles go in and out of style, devices get smaller, accessories are in excess, and every successful bit of gadgetry succeeds older versions into redundancy. The passing of computer game technology is pretty unceremonious. Something dies when its replacement has been spawned. Bye bye Mr. Xbox; hello 360; please plug in your Kinect. This is strategic, as you unpack your iPhone 3GS on day one the iPhone 4 is already in R&D and the latest Fallout title will soon be incomplete as a spate of add-ons are released. It’s called planned obsolescence.

Garnet Hertz and Jussi Parikka talk about planned obsolescence and what they call “zombie media”—the death cycle of consumer electronics and media culture that keeps us collecting ever-better things.

“A more frightening prospect than a past that never can be regained is a past that never goes away. We know this lesson from horror films with the undead, zombies, and other things supernatural that haunt us, but we recognize it from everyday life as well. We recognize it from the heaps of waste and refuse that pile up in our basements, outside urban centers, and in places which are characterized by obsolescence, discarded objects, and things we hope stay forgotten.”

— Zombie Media: Circuit Bending Media Archaeology into an Art Method

They quote some frightening statistics: “400 million units of consumer electronics are discarded every year … like cellular phones, computers, monitors, and televisions”; “the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that two-thirds of all discarded consumer electronics still work.” The scrap heap and the landfill may be the fate of computer-game paraphernalia too, but there are an increasing number of establishments dedicated to preserving computer-game culture.

The Computerspielemuseum in Berlin opened in 1997 and was the first of its kind in the world. It has a permanent hardware exhibit, a software library, and an extensive collection of literature on games from magazines to manuals, as well as visiting interactive exhibitions. They have unique objects including twin VR units and the Jumbo Joystick. The museum collection policy is to preserve digital game objects that are “typical for their time or of artistic, scientific and/or educational significance,” but it also explores the resurrection and adaptation of game forms with art-mod installations, like pong.mythos and Painstation, that give new life to old games.

The passing of computer game technology is pretty unceremonious. Something dies when its replacement has been spawned.

The National Museum of Play in New York is home to the International Center for the History of Electronic Games that holds a vast collection of hardware and software as well as unique materials and ephemera. It boasts a near-complete collection of Prima guides, design documents and business records, themed candy dispensers, lunch boxes, licensed clothing, action figures, and plushies. These endeavors bring to light the secret life of games development, tug at the nostalgia strings, and evoke the narratives of the kids’-meal toys your mom threw away and the Sega spaghetti shapes that went out of date.

In the preservation of the computer game, what is collected is as important as how it is presented. The ViGaMus, due to open this year in Rome, has considered this; and its primary exhibition will be an interactive walk through the history of computer gaming. The space is laid out in chronological frames so the visitor can experience the exhibit as a timeline. Meanwhile the National Videogames Archive in the UK is addressing another curatorial issue specific to the medium of computer games, their interactivity. Games want to be alive. Machines alone, game objects by themselves, are dead things. With computer games in the museum, we are not just dealing with objects dead from cultural causes, but objects that need players to bring them to life. With this in mind, the National Videogames Archive uses the save the videogame campaign to ask the industry how best to preserve games. It’s a diplomacy. And so they are not only actively collecting game artifacts, but also capturing the act of play, games in their live state.

We’re throwing away history because it was made disposable and a wonderful few are treasuring our trash. Vintage, classic, retro, yesterday’s, revolutionary, crappy, popular, and broken games can live to play another day. So say “thank you.”

Image by zavadzky