The computers of the future will not be a pain in the ass

There is data on the floor; there is data everywhere. Two dancers position themselves amidst this tangle of lights and letters. They lie down on the floor and hook themselves up to a series of sensors. Information starts to appear around them, connected to the body part from whence it came by projected lights. As part of the performance piece PU_P3TS, the two dancers start to twitch. Their movements grow into convulsions. More data points flicker around the dancers, following their movements and aping their spasmodic quality. The interface, it appears, can keep up with whatever is thrown its way.

PU_P3TS is a balletic interface. It exists somewhere between the worlds of choreography and interaction design, or perhaps in both. Like most other devices, it responds to user inputs. Yet, as used by dancers, these inputs are performed with far more conscious thought and advance practice than a swipe on an iPhone. PU_P3TS, then, is a gestural interface writ very, very large.

New interface paradigms require this sort of conscious performance. Users have to think through and carefully plan their actions. “Well-developed proprioceptive or kinesthetic awareness of individual body state, such as position, velocity and forces exerted by the muscles is essential when using alternative controllers,” write the researchers Mary Mainsbridge and Kirsty Beilharz. “Dancers are trained to develop this type of awareness and motor control.”

The rest of us are not so fortunate. A layperson’s first experience with an interface can resemble a teenager’s first dance—a lot of movement but who knows where the hands are supposed to go. Over time one learns an interface’s language and diktats until it becomes second nature, but in the interest of avoiding long periods of friction, interface design often progresses in increments.

Fiction is relatively unburdened by these constraints. In film, interface designs can take giant leaps forward. In Minority Report, which was released in 2002 but set in 2054, John Anderton (Tom Cruise), spends much of his time in front of a giant glass screen. Anderton is a PreCrime scrubber: he identifies individuals who will commit crimes in the future and arrests them before they perpetrate their misdeeds. Anderton spends much of the movie in front of the screen, scanning through video-like predictions of future crimes. His glove-clad fingers have a distinctive rhythm as they patter across the screen. Lights on the gloves’ fingertips make this pattern more apparent. “Steven [Spielberg]’s brief was that he wanted the interface of that computer to be like conducting an orchestra,” the movie’s science adviser John Underkoffler later explained. As with PU_P3TS, the film’s interface is a form of performance.

The full extent to which this interface was performative, however, was not readily apparent to Minority Report’s audiences. “Hollywood rumor has it that Tom Cruise … needed continuous breaks while shooting the scenes with the interface because it was exhausting,” write Nathan Shedroff, the chair of California College of the Arts’ MBA program in Design Strategy, and Cooper Design Fellow Chris Noessel in their book Make It So: Interaction Design Lessons from Science Fiction. Try holding your arms perpendicular to their chest for an extended period. It’s uncomfortable. “These rests don’t appear in the film,” the authors note, “a misleading omission for anyone who wants to use a similar interface for real tasks.”

The film’s interface is a form of performance.

Film interfaces are not wholly made out of smoke and mirrors. They are not wholly real, either. Rather, like most fictional works, they are engaged in a running dialogue with reality. Cruise’s flicks in Minority Report and the dancers’ movements in PU_P3TS both point at ways that fictional interfaces can touch on—and extend—the realm of interaction design.

///

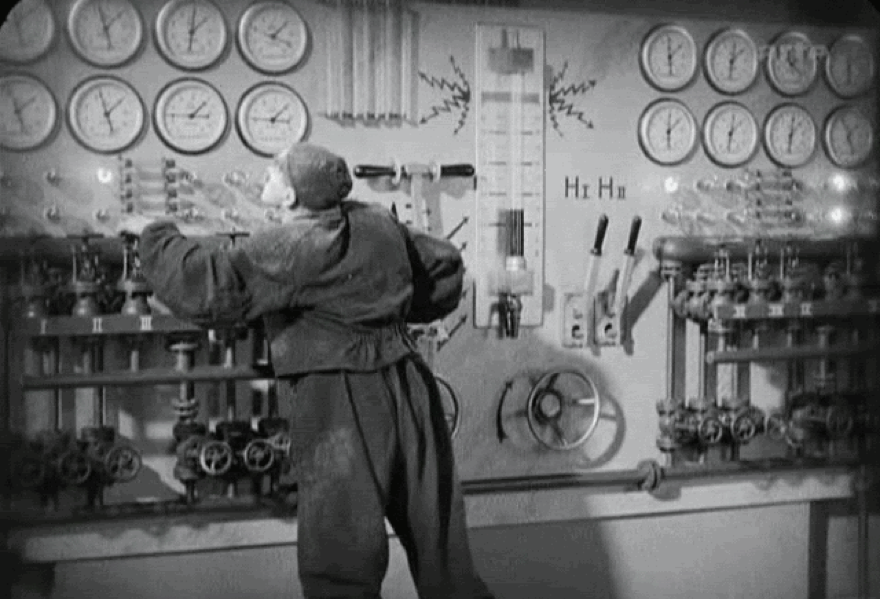

For all of its notoriety—“The Minority Report user interface changed history,” bleats Creative Bloq—Minority Report is not an outlier. As a concept, the interface between humans and technology is broad enough to adapt to the evolving demands of filmmakers. Indeed, before it was possible for filmmakers to reproduce conversations, they could capture the relationship between characters and devices. Fritz Lang’s 1927 opus Metropolis, for instance, includes walls of dials and knobs that tower over the characters. In The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin, Matthew Biro posits: “The interface between human and machine looms large in many of Lang’s movies from the Weimar era.”

Away from the big screen, however, interfaces from movies now loom larger than in the days of Fritz Lang. They are collected in listicles and sorted in digital databases such as Noteloop’s Movie FUI. The authors of Make It So spent five years watching films, taking screen captures, and building a database that could be used to identify patterns. Chris Noessel, the book’s co-author, continues to write about those interfaces on his blog, Sci-Fi Interfaces.

The experience of seeing all of these interfaces side-by-side is uncanny. They are not supposed to share the same narrative universe. And yet, interfaces in films are often strikingly similar. Oblivion’s large screens with dense blocks of data surrounding a rendering of a spacecraft, for instance, appear to be the first cousins of Star Trek Into Darkness’s large screens with dense blocks of data surrounding a rendering of a spacecraft. Beyond such dyads, there are more general similarities in cinematic interface design. In their survey of Sci-Fi interfaces, Noessel and Shedroff found that “the ratio between sans serif and serif typefaces” approached 100:1. Overwhelmingly, the interfaces Noessel and Shedroff studied were blue. The biggest trend, Noessel told me, is that “everything glows.”

“Everything glows.”

“Things that glow blue are uncommon,” he explains “So that combination is a natural fit for something unusual, strange, and powerful.” This combination isn’t solely of symbolic use; it also conserves filmmakers’ resources. The warm lights used on film sets transform the appearance of blues far less than reds, yellows, or greens. Consequently, Noessel observes, blue interfaces require less colour-correction in post-production.

The range of interfaces in film is also constrained by narrative imperatives. Much as characters are never shown going to the bathroom in film, Noessel points out that characters are rarely—if ever—shown fiddling with volume or light controls. Such narrative tedium takes place off-screen. Conversely, film is not currently hospitable to certain interactions that might be of narrative use. Haptic interfaces—physical feedbacks such as the wrist taps delivered by the Apple Watch—are compelling but, notes Noessel “it’s very hard to convey a haptic interface in cinema.” The interfaces that excise narratively superfluous interaction and are most suited to the medium’s demands are large screens packed with vital data. It is no coincidence that such designs populate databases of film interfaces like bands of wild rabbits.

We know what those movements mean.

These patterns—the large, blue, glowing screens; the sans serif typefaces; the blocks of vital data—are all self-reinforcing. Noessel points out that in Minority Report, “[Steven] Spielberg went to great lengths to put lights at the end of Tom Cruise’s fingers so the audience would understand how the pre-crime scrubber knew what his hands were doing.” In 2002, when Minority Report was released, gestural interfaces were new to the screen and to consumer electronics. In 2015, however, gestural interfaces are a familiar point of reference for moviegoers. Cruise’s lighted fingers are no longer required. We know what those movements mean.

With the exception of technology that is central to the plot, Noessel therefore posits that returning to existing tropes makes sense as a means of conserving narrative time. The finer points of interface design are rarely crucial to the story. Other filmmakers are therefore happy to let the likes of Minority Report do their exposition for them. The resultants patterns, Noessel argues, “are becoming self-referential in that a language is developing between the audience and the sci-fi makers and other sci-fi makers.”

///

Although they possess an emergent language of their own, cinemagenic interfaces do not exist in a hermetically sealed environment. They are in dialogue with one another, but they are also part of a larger discourse that connects interfaces in film with the broader field of design.

In Georges Méliès’ 1902 film Le voyage dans la lune, the president of the Astronomic Club, Professor Barbenfouillis, persuades the club’s membership to go along with what he believes to be an ingenious plan to reach the moon: They will fire a bullet-shaped rocket out of an oversized gun. Méliès drew inspiration for his film from then-popular novels including Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon, in which a “space gun” is used to launch a lunar-bound projectile. The idea of a rocket fired out of a gun, which now seems patently absurd, existed in the public consciousness when Méliès’ film was released.

Le Voyage dans la lune is but an early example of a form of fictional recency bias that Chris Noessel formalizes as “what you know plus one.” The aesthetics of science fiction films riff off the prevailing designs of their times, advancing their paradigms but not breaking with them entirely. The year in which a film is made matters as much—if not more—than the year in which it is set. Thus, Sunshine and City Beneath the Sea, which were respectively released in 2007 and 1971 offer altogether divergent takes on the year 2050 and its interfaces.

The “plus one” part of Noessel’s rule gives the creators of sci-fi interfaces an advantage. An abstracted and stretched present can be easier to represent than the real thing. In his videoessay A Brief Look at Texting and the Internet in Film, Tony Zhou observes the divergent paths filmmakers have taken to representing text messages. While the practice of showing texts on screen is increasingly the formal conventions for how these messages are displayed are all over the place. Are text bubbles tethered to characters, devices, or nothing at all? Zhou even points to examples of filmmakers cycling between all of these options within the same scene. Indeed, the solutions to the texting problem are far less homogeneous than collections of sci-fi interfaces. Interfaces that exist in “what you know plus one” carry references from the present but not all of its baggage. Instead of aiming for verisimilitude, these interfaces can establish conventions that are more appropriate for the big screen.

Those conventions, however, trickle back into present-day design discourse. “I wish I could get away with charging my clients a fee for every time they say “Minority Report” to me, ” wrote Christian Brown’s in his essay, How ‘Minority Report’ Trapped Us In A World Of Bad Interfaces. Brown’s contention that the glitz of Spielberg’s film dominates discussions about interfaces is widely held. “Almost every client I have in my day job at Cooper comes and mentions this movie,” Chris Noessel told an audience at a Boing Boing event in 2013. He paused before adding: “For surgeries and financial investigations.”

Fictional interfaces—even bad ones—are points of reference.

“It’s been great for a user interface to have become so recognizable by the general public,” Frog’s Chief Creative officer, Mark Rolston, told The Verge. “But really, it’s a terrible idea.” Fictional interfaces, even the bad ones, provide points of reference from which discussions of real interfaces can originate. Interaction designers’ clients go to the movies, after all. This phenomenon, in homage to Noessel, might be called “future minus one.” You may know it by it’s more common name: inspiration.

The problem with finding inspiration in movies, then, is that filmmakers can cheat. “There’s a huge gap between what looks good on film and what is natural to use,” Christian Brown argues in his essay on Minority Report. Directors working in concert with their actors and special effects can fudge usability. Brown suggests that the perversity of the film’s legacy is that large transparent screens and “touch-screen interfaces, which look great because of how easy it is to tell what a user is doing on camera, have managed to take over our lives.”

The fact that sci-fi has helped popularized dubious interface ideas does not preclude film from also serving a positive role. Chris Noessel says that poring over sci-fi interfaces has caused him to consider technology’s role in our lives. One particular idea came from the pilot of Firefly, in which the protagonist must shoot down spacecraft by matching a fixed reticle (crosshairs) on an anti-aircraft weapon with a digital reticle on the weapon’s heads-up display. “If the weapon knows where the bad guy is,” Noessel asks, “Why is it waiting for Mal (the protagonist) to aim the weapon at all?” Fiction requires its heroes to be heroic and line up their own crosshairs. In the real world, there’s no reason why technology couldn’t do this kind of job for us. (Even as we definitely want the task of pulling the trigger in the hands of a person with a moral and ethical sense.) “That scene and many others like it have me convinced that the next salient aspect of technology is that it will be doing a lot of work for us,” Noessel continues. “Instead of being tool-users, we are going to be tool-teachers.”

This sort of interaction, which Noessel has dubbed “agentive technology,” is an outgrowth of sci-fi that already has tangible applications. Devices like the Roomba or Nest, he points out, only require minimal user inputs. At most, users provide occasional course corrections. “Almost every client that comes to me in my work at Cooper, I think what role could agentive technology play here?” says Noessel, who is now writing a book about agentive technology that is an outgrowth of his work on science fiction interfaces. “And for almost every client, I think, yeah, ‘That could really work here, but is the client ready?’”

Your average consumer of technology is a gradualist. If tomorrow she were to wake up on the set of Oblivion, she would probably be disoriented. The same holds true for Noessel’s agentive future: not all clients are ready, at least not yet. Our discussions about and with technology are always slowly shifting forward. Films, through their conventions and patterns, help us think about what interfaces could one day be. They are informed by our expectations and return the favour by subtly reshaping those expectations. The language of cinemagenic interfaces, like the lighted tips of Tom Cruise’s fingers, sweeps forward.

Roomba Path photo via Wikimedia.