Confronting videogame torture, after the CIA’s report

The Senate’s report on the CIA’s Detention and Interrogation program was released to the public last week. It was a look into the use of torture on detainees by US intelligence personnel, and make no mistake, it was a catalogue of nightmares. Much of it we already knew—the CIA’s use of waterboarding, or simulated drowning, was made public in 2007—but the report contained new grisly details, such as the forced rectal feeding and hydration of prisoners.

Response to the report has been divided, with about half of Americans believing that the interrogation methods of the CIA were justified according to a new national survey by the Pew Research Center. Primarily, the strongest defenders of the Agency have been conservative politicians, chief among them Associate Justice Anton Scalia of the Supreme Court. During a radio interview following the release of the report, Scalia offered his opinions on the subject:

“Listen, I think it is very facile for people to say, ‘Oh, torture is terrible.’ You posit the situation where a person that you know for sure knows the location of a nuclear bomb that has been planted in Los Angeles and will kill millions of people. You think it’s an easy question? You think it’s clear that you cannot use extreme measures to get that information out of that person? I don’t think that’s so clear at all.”

Scalia’s hypothetical—a bomb planted in Los Angeles—was actually explored in another television program, the second season of 24, in which Jack Bauer’s rough interrogation of a suspected terrorist uncovered information of an impending nuclear attack. In 2007, when accusations of torture by American agents first arose, Scalia gave a similar statement. “Jack Bauer saved Los Angeles…He saved hundreds of thousands of lives,” said Scalia. “Is any jury going to convict Jack Bauer?”

Scalia might be right—not that LA is in imminent danger of nuclear holocaust, but that if Jack Bauer can torture someone, even a terrorist, and remain the hero of his cable timeslot, that says a lot about the American relationship to torture.

Of course, cable television doesn’t hold the monopoly on depictions of torture. Last year’s Grand Theft Auto 5 features an interactive torture scene. In it, Trevor, one of the three playable characters of the game, tortures a hapless victim to gather information for the “FIB,” a thinly veiled allegory to the Federal Bureau of Investigations. The most disturbing part of the scene—above the option to waterboard the restrained man with gasoline—might be how cooperative the victim tries to be before each torture sequence. “Are you ready to talk now?” says one of his interrogators, an FIB man. His response: “I’ve been willing to talk since I was kidnapped!” It’s eerily prescient, considering that one of the worst details to come out of the CIA torture report was our torture of willing informants. The scene is clearly intended as commentary, but the game still gleefully allows the the player to choose the tool of torture each time.

Both of the recent games in the Far Cry series contain torture, though in Far Cry 4 it’s almost an optional scene—the player can watch while a government agent tortures a suspected terrorist and monologues about family life in America. Far Cry 3’s torture scene, on the other hand, is put center stage: the victim is protagonist Jason Brody’s younger brother, Riley, who Jason must torture to keep his cover as a hardened criminal. As in the GTA 5 sequence, the game implicates you in the torture—you’ve got to hit the button to make Jason deliver some very un-pulled punches.

Clearly, this is supposed to be a horrifying situation. This forced familial violence is darkly and Greekly ironic. After digging his thumb into his brother’s gunshot wound (which is maybe going a little far to sell the act), Jason looks down at his hands and asks “What have I become?”

This is an interesting question. Has Jason become morally compromised? Well, torturing his own brother is pretty evil, yeah. So was killing the last nine Sumatran tigers to make a tote bag. On the other hand, Jason goes on to continue fighting the red-shirted bad guys, trying to save his friends, and generally fighting the good fight. So, if Jason’s question is “What have I become,” one response might be, “Still the hero of this story.”

While some praised Far Cry 3 or GTA 5 for their writing, many others called them facile, even amateurish. Let’s turn, then, to the narrative powerhouse The Last of Us, which received praise in pretty much all corners for its dark and complex story. When Ellie goes missing, Joel—previously established as a ruthless killer, gun runner and general hard case—restrains two men he thinks might know where she is and tortures them until he gets the information he wants. Then, he kills them both.

So, what does this scene say about Joel? It’s a grisly sequence, and by the end of the game Joel’s humanity is even more compromised, but I would argue that the audience still isn’t against him in the context of this torture scene. His victims were established right away as bad men. They were shooting at him, until he handcuffed one to a radiator and jammed a bowie knife under the other’s kneecap. On top of that, everything Joel does is in order to find and protect Ellie, who we know is in danger, and has become personally very dear to the player by this point in the game with her sassy tongue and heart of gold. Joel’s use of torture is grim, but I think most people would feel that it was, in context, necessary.

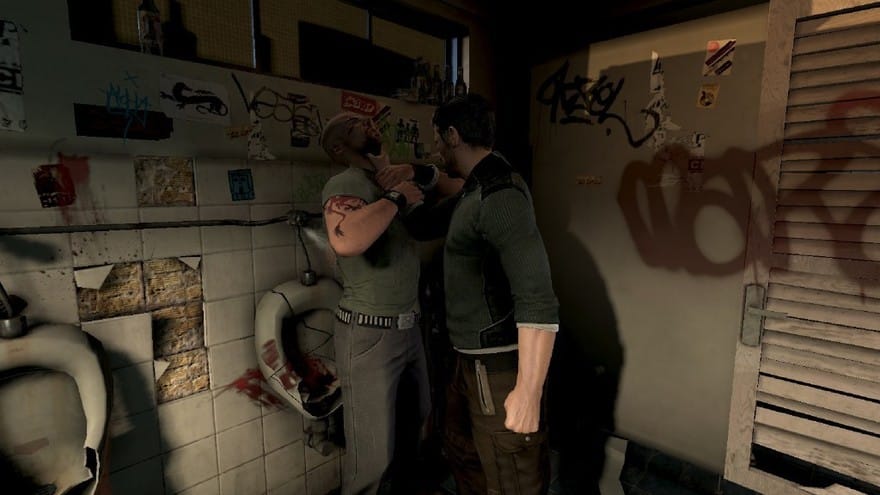

These aren’t isolated cases, either. In Splinter Cell: Conviction, the “interrogation” button is synonymous with smashing someone’s head through a dirty urinal, which Sam Fisher does without a second thought. In Call of Duty: Black Ops, two of the main characters place a shard of glass in someones mouth before socking him in the jaw in order to get him to talk. Even in the far-off future of Mass Effect 2, a Commander Shepard indulging in a renegade prompt can, during an interrogation with a crime boss, bloody his nose and threaten to “cut his balls off and sell them to a krogan.” Why any krogan would want to buy them is, thankfully, left unsaid.

A pattern begins to emerge when these individual portrayals of torture are examined as a whole. Yes, videogames understand that torture is bad; often, it is portrayed as gruesome and even evil. The problem is that games keep putting their protagonists in the role of torturer. Regardless of whether they are willing, enthusiastic torturers, or driven by desperation, they’re more often than not the heroes of their story. They are the Jack Bauers, if you will, and few players would convict them.

If developers want to use torture in their games to make them more “gritty” and dark, of course, that’s their right. It becomes problematic when the portrayal of torture in nearly every game fails to address one of the most divisive sides of the issue: its effectiveness in providing reliable information.

Consider this: never, in any game, does a character get unreliable information from a victim of torture. Joel finds where Ellie is being kept, Sam Fisher finds the terrorists, and—even while monologuing about the ineffectiveness of torture—Trevor gets the information he needs for a successful assassination. Compare this incredibly high success rate with the findings of the report, which were that “enhanced interrogation techniques” actually provided very little actionable intelligence. That’s G-man talk for accurate information; almost every successful operation in the torture report was driven by information gathered from bribes, willing informants and wires, not torture. In games, though, torture works. It may be an evil action, only undertaken by the most desperate of heroes, but it works. This leads me to wonder if the reason that 51 percent of Americans feel that the CIA was justified in its use of torture is because of our entertainment, whether it’s 24 or The Last of Us, which shows that torture is effective, rather than frequently misleading, as it is in reality.

A close look at these portrayals of torture points to either cognitive dissonance or an exceptionally cynical, Machiavellian mindset that is, on reflection, parallel to America’s own tumultuous and questionable relationship with torture. These games, intentionally or not, posit that we, as players, may do a bad thing, but as long as we’re doing it for the right reasons, we can still be the hero of the story.