Even as tablet usage has exploded, only something like 8% of users look at them as replacements for their laptops. Instead, these devices occupy an intermediary space, something their software has to accommodate. The singular mix of size, power and limited input force game developers looking to work in the tablet space to work within a new syntax and grammar of gaming experience. Over the next few weeks, iQ and Kill Screen will explore these questions.

The website for game studio Simogo, creators of hit mobile titles Bumpy Road, Beat Sneak Bandit, Year Walk and the just-released Device 6, is organized by the expected categories: About, Games, Blog, Contact. A small graphic illustrates each, drawn by co-founder Simon Flesser in his inimitable style: the About page shows two smiley-faced PlaySkool characters, representing Flesser and programmer Gordon Gardeback; Contact shows an envelope. Under the Games headline is a simple, rectangular controller, complete with cross-shaped directional pad and four buttons, an invented amalgam that nevertheless immediately makes sense as a symbol for play. Until you realize that Simogo’s five games have all launched exclusively for iOS, a controller-less platform.

“Our website is three years old, so we really should change some things,” Flesser laughs. But he concedes the D-pad and buttons are still the iconic image of gaming, even if his own games and many others don’t use them. That icon is swiftly changing.

The controller has long been the default option for how we play videogames. From the onset of the gaming boom, with Atari’s singular joystick making way for the NES’s iconic gamepad, we’ve played with our hands, the controller a necessary talisman, interpreting our desired moves into the nimble action of an on-screen avatar. Yet for half a decade, mobile devices have snipped the cord between player and play, giving us direct, tangible control. It’s not hard to imagine a generation of players for whom a D-pad is a typo and buttons are a shirt accessory. We touch our games now.

The capacitive touchscreen and integrated accelerometer of smartphones and tablets have become the dominant input by sheer force of numbers. Sony’s PlayStation 2 is the most successful console of all time, with over 155 million sold after ten years on the market. But Apple announced last month they had sold 170 million iPads since its release in April 2010. Swipes, pinches and taps are the A and B buttons of the present.

What before required discrete inputs and two hands now only needs a single finger. Slice towering knights in Infinity Blade III. Run and jump through beautiful hand-drawn flora in Rayman Jungle Run. Organize tetrominoes while managing space and time in Rymdkapsel. Navigate an albino ball down floating paths in Impossible Road. The breadth of play available for games built around mobile device’s native capabilities is wide and rich. Those games with shoe-horned button-control are better played elsewhere.

It’s not hard to imagine a generation of players for whom a D-pad is a typo and buttons are a shirt accessory. We touch our games now.

And yet there remains a segment doggedly holding onto the controller as “the one true way.” The OUYA, GameStick, and Nvidia’s SHIELD all put a physical gamepad in your hand to play games often developed originally for phones or tablets. There’s a rising call for Apple to make their own controller to use with their uber-popular devices. Samsung has already announced an official gamepad for their Galaxy Note tablets, adding buttons and sticks where before there was only smooth glass.

As a player of button-based games for three decades, I understand the desire for tactile feedback; I prefer the snap of a physical switch to the alien responsiveness of capacitive technology. But to control a mobile game with buttons is to suture a wound where none exists. The push to force controllers into the hands of mobile gamers is robbing tablets of their power, turning them into lesser TVs.

Flesser understands the power of a blank slate. “There’s something very joyful in having to invent the way you interact… for every new game,” he writes in an email. As a player, he says he’s most interested in non-traditional interfaces, those that ask you to learn a new way to play, not rely on simple muscle-memory. The traditional joystick, buttons, and triggers found on standard controllers have been mapped onto so many actions and kinds of gameplay that it becomes increasingly hard to forge new ground. When smartphones and tablets grew relevant as gaming devices, their touch-screen was fertile territory, relatively untilled. Nintendo’s DS handheld employed a touchscreen long before the App Store exploded in popularity, but the dual-screen system had its compliment of buttons. An iPhone’s entire viewing window is its input device, affording the direct simplicity of ancient tactile games like Go. You want to move a puzzle piece? You reach out and touch it.

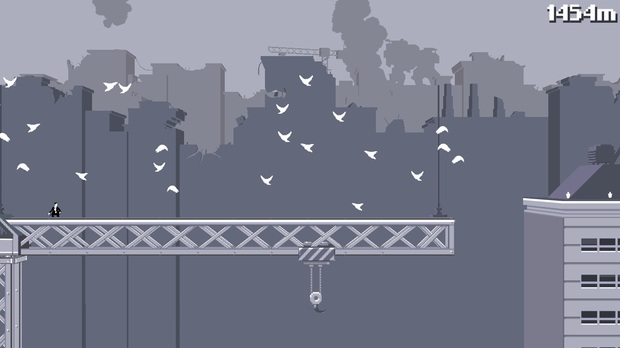

The lack of options also enables players with little controller proficiency to try a mobile game, where its controller’ed cousin might breed intimidation. You want to jump a chasm between collapsing buildings? No need for complicated button patterns. Just tap anywhere. Adam Saltsman designed such a game in Canabalt. Anyone put in front of the game intuitively understands the goal: To run across a never-ending series of rooftops as society crumbles around you. The easy controls and intriguing style (not to mention Danny Baranowsky’s driving soundtrack) propelled the game into one of the App Store’s early blockbusters. But it was Saltsman’s work with Greg Wohlwend’s browser game Hundreds that showcases the innate benefit of touch-based controls.

“Everything we added was [done] with the touch-screen in mind,” Saltman wrote to me. Hundreds is a minimal puzzle game with a screen full of circles. The devilishly simple concept? When you touch a circle it grows in size. A number increases within its perimeter. Add up the circles to 100 to win and move on. But if any of the circles touch, you die.

“We practically had a list of ‘What are interesting things to do with fingers on glass?’” They implemented as much as they could, but the simplest change was arguably the most important. Before, you scanned your finger across a trackpad, which moved a cursor onto circle-enclosed numbers on-screen, and then clicked. Now all you did was press down.

“Not all games work like that,” Saltsman reminds me, and certainly, for some games an attached controller can give your tablet the sturdiness of a clicked button or familiar toggle of a joystick. But then the small screen reverts to just that—a screen only—where before its form and function were all-inclusive. Design with a controller in mind and you’ve neutered the device, cutting away its inherent strengths.

Design with a controller in mind and you’ve neutered the device, cutting away its inherent strengths.

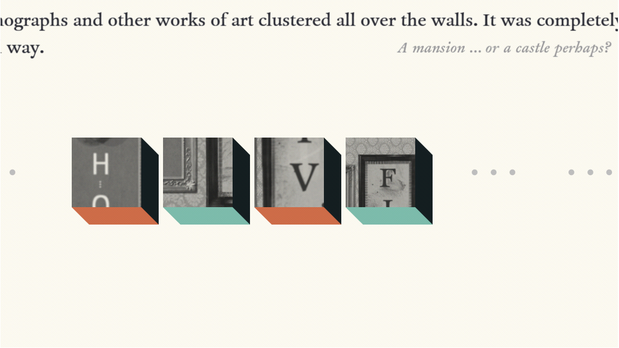

Simogo’s Device 6 taps into more than just the ease of tapping. More and more we read our books on digital platforms, from Kindles to iPads. Device 6 is, essentially, an interactive novel, where we scroll through words on this screen-as-page. But this page does things paper could never do: Words move, shrink away, bob in rhythm, hide around corners. We move through the text as we would a dungeon searching for the next torch to light our way. And it feels natural, holding this “Device,” because that’s where we’d be reading anyway.

Flesser acknowledges the tablet’s form didn’t influence their recent game; it was simply the story they wanted to tell. But he sees controller-less platforms instilling more creativity into game design than the staid standard of buttons.

“There has been so much work done there already that it’s easy to look at the traditional set-up as some sort of standard,” he writes. “There’s nothing to learn.” But maybe the greater benefit is beyond clever mechanics or new, novel ways to interact with glass and plastic. With touch and motion controls, players can worry less about learning the language of the game, and instead explore the game “with interactions they already use in their everyday life,” Flesser writes. “Perhaps even in a more human way.”