The Coral Cave, and the art of turning Okinawa into a watercolor world

After living in Niigata for a year, Cécile Brun and Olivier Pichard had become obsessed with what they discovered: Japan’s countryside, and the people and folklore that comes with it. It was after this that the French couple, both artists, decided to travel back to Japan as often as possible, and to work on projects based on these travels under the studio name Atelier Sentô.

One of these return journeys saw the pair hopping from island-to-island around the picturesque archipelago of Okinawa. Over the course of that month-long stay, Cécile and Olivier produced many sketches of what they saw—as they always do—and it’s these that became the start of their first videogame project, The Coral Cave.

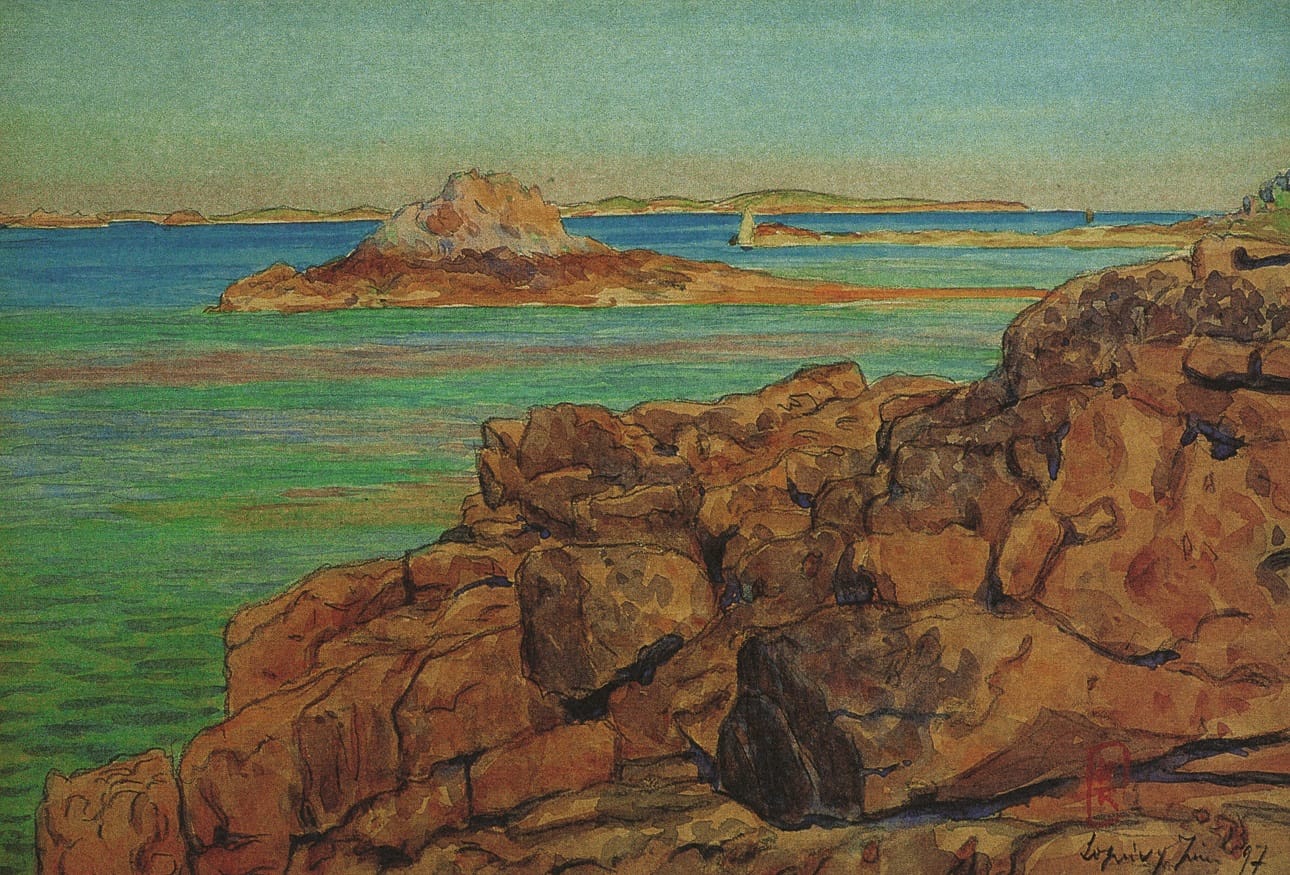

turned the mystic and stony shores into watercolor paintings.

This much we already knew about The Coral Cave, but there’s much more to crafting the game’s watercolor world of childhood exploration and mysticism than simply transferring those sketches from paper to software. While Cécile and Olivier have refrained from researching Okinawa, preferring instead to relying on what they “saw and experienced during [their] trip rather than looking for abstract information in books or on the internet,” they have been influenced by many other artists in how they’re depicting those islands. This was the subject of a recent discussion I had with them.

Low tide, Loguivy, July 1897, Henri Rivière (La Bretagne, aquarelles inédites, Equinoxe, 2004)

One of the most important artists to Cécile and Olivier is Henri Rivière, who is a fairly well-known French artist that was especially inspired by Japanese ukiyoe (described as “pictures of the floating world,” mostly realized as woodblock prints and paintings). The pair discovered him and his art when living in Bretagne, where Rivière traveled around as he turned the mystic and stony shores into watercolor paintings.

For Cécile and Olivier, it is Rivière’s woodblock prints that stand out in particular, as they describe them as some of the most beautiful examples of combined Japanese and French art. “The Coral Cave was only beginning when we bought Rivière’s sketchbook and we spent lots of time flipping through it,” they told me. “His sketches look very modern because of their composition and their vibrant colors. We also like the thick lines (while watercolor artists usually try to have invisible lines) and the omnipresence of water.”

Pastoral: To Die in the Country, Shûji Terayama (Art Theater Guild, 1974)

Another huge influence on the pair is Shûji Terayama, who was a Japanese avant-garde poet, dramatist, writer, film director, and photographer who was particularly prolific during the 1970s before his death in 1983. Cécile and Olivier go so far as to say that their “entire vision of Japan has been contaminated” by Terayama’s work. They have no words to describe what he created themselves, but claim that they see more ideas in a single camera shot composed by Terayama than most films convey in their entire running time.

a mother screaming the name of her lost daughter over the sulfuric lake.

Of Terayama’s films, they say he depicts a Japan that seems to have been composed by fantasy, but in fact it is not at all, and most of what he captured still exists today. “We traveled twice to Osorezan, the Mountain of Dread, where Pastoral: To Die in the Country was shot,” Cécile and Olivier said. “It’s a desolate volcano, one of the most sacred places in Japan. Parents come to contact the soul of their dead children. We’ve seen huge crows in the smoke, quarreling over kid’s snacks left as offerings. We’ve heard a mother screaming the name of her lost daughter over the sulfuric lake. And a thousand jizô—childlike figures of stone—were watching us with their enigmatic smiles.”

What The Coral Cave takes from Terayama is the link with childhood, the reconstruction of reality through dreamlike memories, and the phantasmagorical imagery of old Japan.

Mirai-chan, Kotori Kawashima (Mirai-chan, Nanarokusha Publishing, 2011)

It’s not as rich in presence as Rivière or Terayama, being described has having only a “subtle scent” inside the game, but the charming photobook Mirai-chan also has some sway on The Coral Cave. It was produced by photographer Kotori Kawashima and depicts one four-year-old girl’s life over the course of a year as she grows up on Sado Island in Niigata. Its location is mostly why it interests Cécile and Olivier, but they also say that the contrast between the young girl and the old house she lives in, surrounded by these unique ominous landscapes, also made a big impression on them.

“What interests us here is this juxtaposition of a very young girl from today and an ancient mysterious world,” they told me. “She may look out of sync to the reader, but Mirai-chan simply lives there. Everyday life can be an adventure. Just open this book and stories will start to take shape in your mind!”

The Song Thief, Daisuke Igarashi (Kaijû to Tamashii, IKKI Visual Book, 2012)

Looking at the image above, you can see the obvious similarities between it and the blue skies and splashes of The Coral Cave‘s look, but its source isn’t one that Cécile and Olivier usually consult. It’s from a manga called The Song Thief by Daisuke Igarashi. The pair at Atelier Sentô say that they don’t usually read manga as the art focuses on characters’ faces while backgrounds are only there to tell you where a scene is taking place. This isn’t so much the case in The Song Thief.

“Daisuke Igarashi draws everything with the same sensitive line, elegantly connecting humans and nature. He truly believes in this link and puts it at the center of his stories,” Cécile and Olivier told me. “Even in the middle of the city, no one is independent from nature. Our eyes are closed and Igarashi’s stories are all about opening them.“

End of a Trip, Misao Shimizu (Kâchi-bai, Art Box Gallery, 2002)

Last on this list of influencers are the paintings of Misao Shimizu. Cécile and Olivier say they came across the paintings in a second hand bookstore in Sendai, back in August 2012—a book, they say, that follows them everywhere. They were drawn to the magic contained within the images in this book, which they describe as “emitting light.”

It’s an unusual quality to give them as Shimizu focused on creating accurate paintings of Okinawa’s landscapes. But the context in which they discovered this book of his paintings may help our understanding of this reading. “We were spending a few days in Ishinomaki, a city that had been terribly damaged by the tsunami the year before,” Cécile and Olivier explain.

“it helped us to handle the sadness.”

“In our way to attend a small matsuri (a traditional festival) on a sacred island, we walked across devastated areas. Entire villages wiped off the map. It deeply affected us. When we opened Misao Shimizu’s book in that bookstore, it instantaneously brought us back to the warm ambiance of Okinawan islands. Somehow, it helped us to handle the sadness.”

Knowing all of these art works that Cécile and Olivier have incorporated into their own creations,, and understanding what they take from them, should help to convey what’s so special about the Okinawa that they’re trying to depict in The Coral Cave. It’s not one made of facts and figures, nor one based purely on experience, but enhanced by the multiple lenses and paintbrushes with which Japan’s most beautiful sights have been captured. Cécile and Olivier are hoping to evoke sadness, joy, spirit, adventure, and magic purely from the visuals in The Coral Cave, and they’re taking their time to ensure that comes across.

You can find out more about The Coral Cave on its website. It will be released for PC whenever it is ready.