The creepypasta hell inside Animal Crossing: New Leaf

Do you remember Aika? Animal Crossing: New Leaf had a robust fan culture for a surprisingly long time after its release, where players shared their trials and tribulations and creations with others. Among all the screenshots and stories and Let’s Plays, though, there was a strange phenomenon that gained some traction, and Aika Village was its centerpiece. Understanding the phenomenon means experiencing Aika, or at least understanding what was there to be experienced, and how.

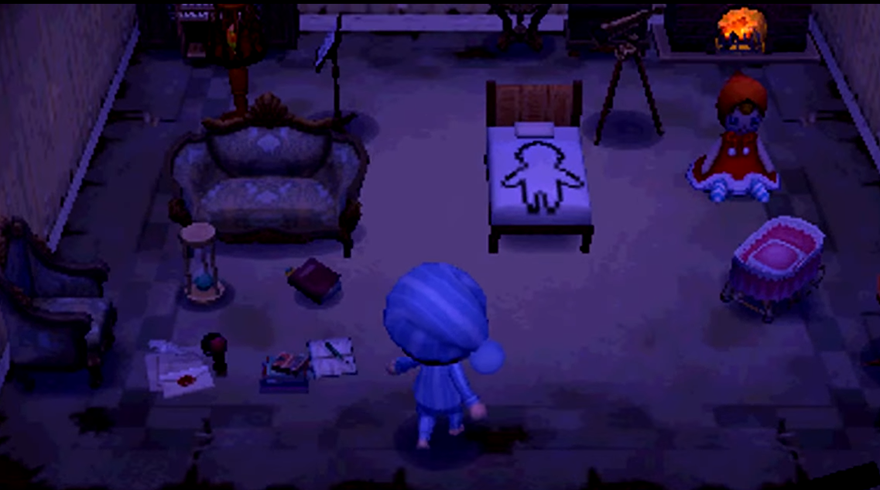

Possibly the most unique feature of Animal Crossing: New Leaf was a little building off in the corner of town called the Dream Suite. The Dream Suite was new to the Nintendo 3DS version of the game; once unlocked, the Suite would allow the player to visit other players’ towns without having to know them or being able to affect their towns. You could chop down as many trees as you like, bury villagers in pitfall holes without them threatening to leave, or get design ideas from random strangers. Or, as Aika showed, you could take in a guided experience, complete with effective horror narrative.

You could take in a guided experience, complete with effective horror narrative.

Like many things in Animal Crossing, the Dream Suite is initially unavailable to the player of New Leaf. To unlock it, you have to be the mayor for at least a week; after this, visit the town hall occasionally until you catch your assistant, Isabelle, asleep at her desk. When you wake her up, she will add the building to the list of Public Works Projects that you can build. Once it is chosen it still must be funded; once it is funded, it will be built. With the Dream Suite comes Luna, its attendant tapir, who teaches you how to use it and stands by while you dream in other towns. She also offers, once you lay down in its bed to sleep, options on what sort of dream to have; one at random, one by searching, or one by dream code.

Enter Aika’s Dream Code, and your character will wake up in a dream on a ground covered in what looks like television static. A present is next to the bed in which you wake, which can be opened to reveal a doll. The static is dotted with beautiful fountains, and, once the player moves out of it, the town itself is, at first glance, beautiful. The ground is carpeted with rare flowers and fruit trees, and the first house is a pleasant experience. On the main floor, a birthday party is being held for Aika. The back room is blocked off, and the upstairs room is a child’s playroom with some drawings. The only thing off is the music; a slow, reedy melody seeps through the scene.

To get to the rest of the houses, the player has to cross the river. Immediately over the bridge is a hedge maze full of discarded goods and holes everywhere. In one corner is a graveyard—once full of “doghouses,” in a more recent update full of dolls—and a police station full of beehives. The second house is significantly more abstract than the first; the main room is a dark maze, with other rooms having set-pieces like an Adam and Eve room, and a room full of dolls feasting and one hiding an axe behind its back. Further along the town continues to decay, and the subsequent house has similarly abstract set-pieces, although with more explicit horror imagery.

The fourth house is in an area of the town even more decayed, and it exactly replicates the initial house in layout. The birthday party is gone, though, and the back room is accessible; in it, Aika stands with the doll and its axe. The playroom is identical except that the drawings of family members are crudely crossed out. Going to the beach is a sort of coda; a pair of shoes rests near the surf, and a lonely grave is hidden in a small, out of the way section.

The appeal of the Animal Crossing games is that they allow the player to create their own spaces, and to live in them. From the way the games mimic real time (day in the game is day in real life, as is night, and seasons change based on the calendar) to the quantity and quality of the catalog of items, Animal Crossing wants the player to make the game their own while still offering its suggestions, in the form of little metrics like the “Happy Home Academy” that ranks houses based on their beauty. Part of this making is enforcing certain strict limits; the most famous, a character named Mr. Resetti who would yell at the player if they didn’t save the game before turning it off, was largely removed from Animal Crossing: New Leaf, but things like the character and the town layouts being fixed once chosen remained.

The appeal of the Animal Crossing games is that they allow the player to create their own spaces.

This is the hidden power of Aika: the simple act of guiding the player through the town and to the houses in order requires a mixture of planning ahead—finding the correct town layout, for instance—and problem-solving within the affordances of those plans, as in the hedge maze, to even allow for a technique as apparently straightforward as pacing. It’s only once this is done that the work of establishing characters and developing events can take place, and Aika again delivers this with its mixture of beats both narrative (the repetition of house layouts) and interpretive (the more abstract center houses).

///

Have you heard the one about Ben Drowned? Likely you know, at least, of Slender Man, and that he was birthed around the “campfires of the Internet” known colloquially as creepypasta. Creepypasta is a genre of storytelling unique to the Internet, written mostly by amateur authors for audiences of their peers. Written mostly in first person, in the style of conversational writing or diary entries, creepypasta’s subjects range from uncanny objects to the overtly supernatural, and it exists primarily to cause horror or terror or discomfort in its audience. Slender Man, the most famous thing to emerge from creepypasta, is a tall figure with a blank face, a suit, and tentacles, who was created in a contest in the Something Awful forum in 2009 and has since been the subject of independent games and films.

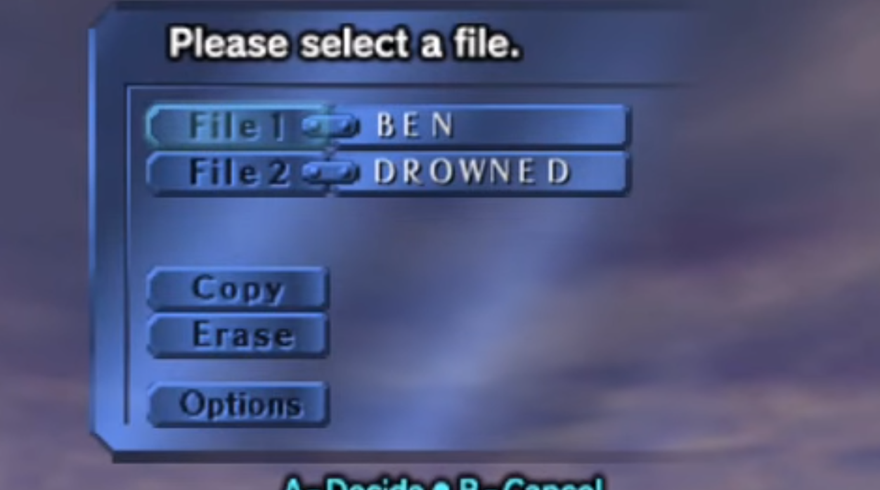

Ben Drowned comes from the same cultural space. The story is about an unlabeled copy of The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask found at a yard sale, and the unliving thing that a college student found inside of it. The story itself begins fairly rote, as creepypasta goes; the forum poster/narrator, identified by his handle Jadusable, reports on some weird things that happened when he started playing a copy of the Nintendo 64 classic found in a yard sale. As the story progresses, the game begins taking over Jadusable’s computer and eventually his life, even as it becomes clearer that the program/revenant is redacting even the work being made available. Jadusable ultimately succumbs to the ghost in the machine, which initially seems to be the ghost of the previous owner but ends up seeming more like a malevolent presence using the previous owner’s identity.

One of the unique things about the Ben Drowned creepypasta was the method of delivery; though it started on 4chan’s “paranormal” imageboard (a common source of creepypasta), it was not simply a running written update of Jadusable’s experience. He included footage from Majora’s Mask that corroborated the descriptions he gave. He even, eventually, expanded on the world in an unfinished ARG and a yet-to-be-released videogame. Jadusable wasn’t the first to explore multimedia creepypasta, or to transfer the setup of the Lost Episode subgenre into videogames, but his combination of the two, and his ability to execute on it, makes Ben Drowned something of a milestone.

One of the unique things about the Ben Drowned creepypasta was the method of delivery

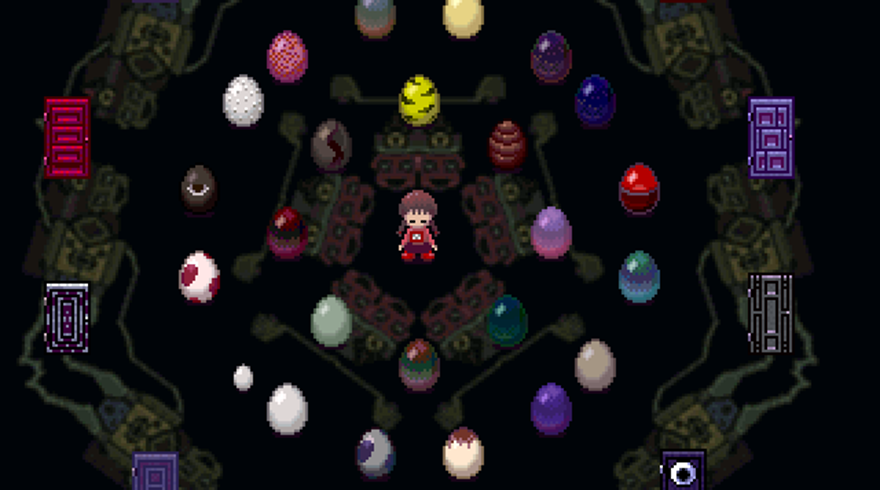

The immediate predecessor of the so-called Nightmare Suites in Animal Crossing: New Leaf, however, is older. The freeware game Yume Nikki was initially released in 2004 and updated until 2007 and built using RPG Maker, a tool for easily developing games in the style of roleplaying videogames from the 1990s. The game features a young girl named Madotsuki wandering through alienating dreamscapes. The particularities of these dreamscapes—especially the characters that reside within them and the interpretive possibilities they provoke—are Yume Nikki‘s focus, but it’s the wandering that defines it. By abstaining from common tropes like the “game over” screen or threats of immediate violence, Yume Nikki can produce terror in the player (as any horror media must at least attempt) while remaining a space that seems, if not safe, at least inviting. Players of Yume Nikki are inspired to wander through Madotsuki’s dream world not because of their terror or in spite of it, but with it. And for many, that invitation extends beyond the game or themselves, and the desire to wander doesn’t end with the “completion” of the game. It spirals out into theories and interpretations, and then into Let’s Plays and fan games and art and communities. It is this last aspect which marks Yume Nikki as a predecessor in a material sense as well as an aesthetic one. Aesthetically, New Leaf’s nightmare suites rely on the inferential wandering style of Yume Nikki. Materially, while there is little apparent direct overlap between the RPG Maker community and New Leaf‘s, the model of sharing on blogs and forums is directly descended from the kind of communal space that was crucial too and supported by Yume Nikki.

Stories like Ben Drowned, and the culture of creepypasta that it was born into and that it helped develop, play a different role in understanding the nightmare suites. Without being a direct precedent to villages like Aika, it helped solidify the terms of their reception. Yume Nikki paved the way, but without Ben Drowned—and Jeff the Killer and Lavender Town Syndrome and Slender Man and the universe of reddit user m59gar; without, in other words, creepypasta—the response to games that followed in Yume Nikki‘s footsteps would likely be more or less the same as the response to games by folks like Kenji Eno, the director of the vampire-cannibal-FMV horror game D and the abstract reproductive (in a sexual sense) puzzle game You, Me and the Cubes. The malignant techno-revenant in the Majora’s Mask cartridge (and its ilk) created not just new ways of thinking or talking about media, but new codes, memes and mores in acting about it. Eno still receives little more recognition than “lol, trippy;” with Aika, and the massively popular creepypasta-inspired Five Nights at Freddy‘s series, that is finally beginning to change.

///

Maybe you don’t remember Shachipanda (a.k.a. “Druggy Village”) or Diablo (a.k.a. “Town of the Artist”), though. There was Hirokui, the town of cannibals, and Haven with its religious cult; Cuteland, where a girl went missing, and the bloodbath in Aniville. Each of these, and many others, told stories; some about uncanny objects, some about the overtly supernatural, and some simple bloodbaths. These towns, much like any individual creepypasta or RPG Maker Horror game, can seem slight taken on their own; Aika’s precedence didn’t necessarily translate into good design practices in its successors.

Exploring other towns reveals the pitfalls that Aika avoided; another of the most famous, Diablo, itself something of a tribute to Aika, features evocative imagery of the same doll that plagues Aika Village emerging from paintings of a forest. Diablo itself relies on a gimmick, though; the central room of both houses is full of clocks, by which the player is meant to infer that the story in the house is meant to be discovered by taking the rooms in clockwise order. By the time this is realized, much of the potential for a guided narrative has been squandered. The guiding lines of Shachipanda are confused by the layout of the town’s paths; not irredeemably, but enough that it becomes a noticeable problem. Most other towns failed to find the correct mix of narrative demonstration and thematic abstraction.

There is even a town, the romanization of which reads Chikuen, that features a strange mash of World War II-era fascist iconography and Pikmin worship. There’s a potential reading that points to it as a wry commentary on the reactionary impulses inherent to certain forms of nerd culture. Probably not, though. Narrative design is as important for a nightmare suite as it was for Yume Nikki, or for the walking simulator subgenre of adventure games like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture; no matter whether the images or the narrative is more essential, the mode of delivery matters. Strong designs like Aika lead the player through a story without their thinking; muddled ones like Chikuen become messes of discarded meanings. These messes, though, are necessary; just like the nightmare suites would not exist without both Yume Nikki and the community games it spawned, and creepypasta needs both Ben Drowned and a million other little, unremarkable stories to change the way that similar media are reacted to, Aika exists in relation to its milieu even as it rises above it.

In these messes and design flaws, there are also interesting expressions of possibility. Shachipanda may have maintained its less-ideal design, but it explored a possibility that Aika never quite managed. The town’s initial version is well documented across the Tumblr and YouTube, but at some point in 2014 it underwent a [transformation| http://uninterpretative.blogspot.com/2014/07/shachipanda-episode-2.html] where the creator uploaded an entirely new version. In the new version, the town’s presumed “dead girl,” named Yamui, has her dialogue changed from, roughly, “These are my dreams and memories” (written in an admixture of hiragana and katakana, indicating that something was very off) to the (all hiragana), “Nice dream, wasn’t it? Because it was a dream!”

At first, I wondered if this update wasn’t doing something similar to serialization; beyond the updated dialogue, the houses themselves had been changed in such a way as to alter the narrative. Yamui’s claim seemed, to me, to indicate something more than just a meta-commentary on the nature of the interaction (her “dream” taking place in the Dream Suite); it recontextualized the nightmare not as a fixed place, but as an ongoing narrative.

“Nice dream, wasn’t it? Because it was a dream!”

By early 2015, Shachipanda had changed again. Some of the changes from the 2014 update stayed intact, but the newest version of the town seems more similar to the original. The dialogue from all of the characters has been erased, replaced only with a single asterisk. Excepting, of course, Yamui; she now responds to a speaking prompt with, in English, “. . . . thirsty.”

Aika, too, has changed over time; the graveyard of dogs became a graveyard of dolls, and Aika now speaks in full sentences like “This is inside of my dream” rather than garbled characters. But these feel like development and clarification on a discrete story, where Shachipanda seems to be doing something closer to a conventional creepypasta, and to the spirit of Animal Crossing at the same time: speaking conversationally, and updating over time. But it also produces its own possibilities. New Leaf‘s little nest of nightmares might not change the face of amateur horror, but it will be there to help interpret it.