What happens when games account for the players’ identities? Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s work does just this. Traversing game design, performance, and sound art, the London-born, Berlin-based artist constructs stratified game experiences that depend on the player’s privilege. Someone who identifies as Black and trans will have a distinct gameplay experience; someone who identifies as cis and white will have a different one. Being careful about access, Danielle tells us, helps keep the archive autonomous. Her work not only fills in the gaps and ruins in the current archive but builds an archive for the future—one that centers on the Black trans experience.

Here, we speak with Danielle about the archive as an always-moving thing, why she’s attracted to low-fi aesthetics, and her new fascination with pirates.

Do you remember your first creative impulse?

My first in to an art world was the burlesque and performing art scenes. I would go multiple times a week to see queer performers, drag queens, stage performance in small venues. I ended up meeting Travis Alabanza, who introduced me to the word trans. At that point, I was just living my life without having the words to describe what that is.

This scene introduced me to different ranges of trans people; people who implemented the experience into song, people creating videos, people dancing, naked people bouncing. That’s when I tried to start making things that were to do with Black trans-ness. I tried to capture what was happening; the forward-thinking conversations in these spaces. I wanted to capture that moment where an environment was made for you.

You’ve cited Telltale’s The Walking Dead as an inspiration. What was it about this game that captured you?

It was the first time I encountered something that was as compelling as a TV series in the form of four entire games…where I wanted to watch the next episode instantly; where I was terrified for my characters; where when someone died; I was really upset. It showed me that the format of these video games can do more than just shoot people.

The Walking Dead uses the simple mechanic of watching what’s happening and then choosing what will happen next. I’d never experienced something where your choices would determine what would happen; the mistakes you made stayed in view forever. The way the game makes those choices matter in a way that spans the generation made me reconsider how games challenge the viewer.

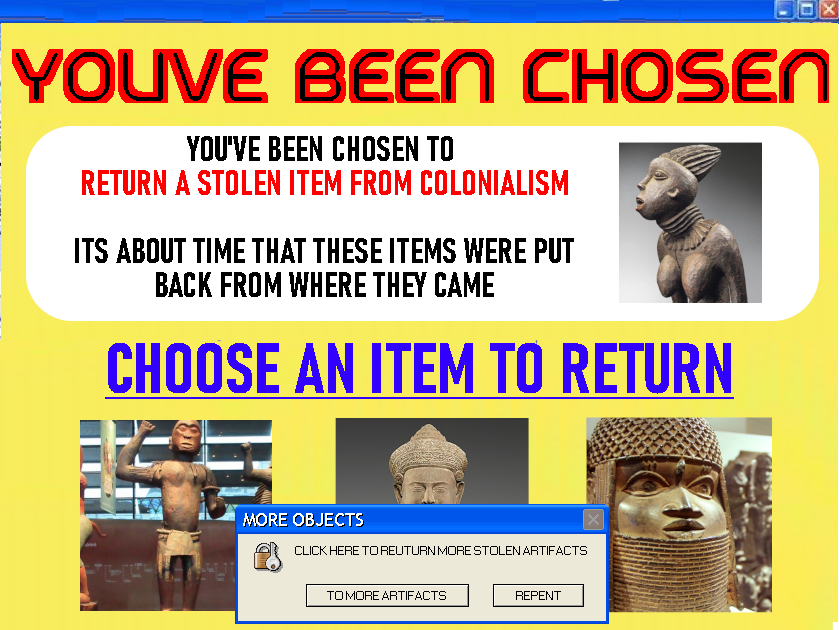

Stills from "BlackTransArchive."

Your project BlackTransArchive contains many layers of opacities. How did you go about constructing these different levels of access depending on the level of privilege of the player?

BlackTransArchive was my first interactive internet archive. It was a collaboration with a number of Black trans people in London. We also worked with a charity called METRO Transcend. These character choices came from these conversations. The landscapes were also designed by the stories told. The interactions in the game came from a role-play session in which we talked about how these characters would interact with each other in this archive. It was like, OK, this person wants to burn cis-city, this person wants to talk about hormones, that kind of thing.

Originally, there wasn’t an idea to make a cis game and a Black trans game. When we talked about access, we wanted to ensure that everyone who’s Black and trans can visit this place. The problem with that is once it’s online, anyone can access it. We decided to make choices for each person’s identity so that what they see depends on their identity. That came from the group discussion.

An archive is accessible to everyone. It was important to make sure that the person’s identity becomes part of the experience, rather than them thinking that it’s a chance to look through a trans person’s eyes. That wasn’t what we were trying to do.

Stills from "BlackTransArchive."

What can the medium of games offer as an archive, or a counter archive, especially in relation to Black transness?

It comes down to me being tired of people consuming things very easily. We live in a world where the point is to make something consumable. I love access, but I don’t like things being passive.

I wanted to make something that told you it wasn’t dependent on your choice. Whatever you chose determined what was shared. It wouldn’t start without you actively being involved—but also, the game could kick you out depending on the choice that you made, because it has a particular terms and conditions to it.

Something about this autonomous archive felt safer to me. It’s exciting because it means we can start protecting certain things in the archive. It’s important to ensure that those within the archives are actually centered rather than whoever’s in charge of it.

For example, Harvard University owns an archive of slave images; these images are horrible. A woman is suing them because the people in some of these photos are her family. Harvard said, Don’t worry, no one can see these pictures. We just have them and they are not accessible to anyone.

Archives should be accessible in some way for them to be seen. At the same time, if you’re archiving violent things, and you use them again in a violent way, then you have a system that perpetuates the violence that the archive itself is a record of…all while pretending to be neutral.

You used archival material and imagery as textures in the game world.

It’s not my secret, but you’d never know it. At a certain point, 3D modeling became my diary. I would put anything from my day into these virtual environments—whether it’s pictures, sound, tests, hormones—and try to fashion something from it as a way of learning. I was also trying to make something that was for me. That’s morphed into me making environments that feel distinctively Black and trans; from my perspective.

This process of using photos I take to make textures has been part of my work for a long time. For instance, I make grass textures out of pictures of hair. As many layers that can be Black and trans as possible, that can represent the person and in a kind of archival sense, means that when I’m writing a story on top of that, there’s the foundation to hold it.

I work in excess. That’s who I am. I don’t know if more is better, but I pare down if I’m trying to do something simple, it’s still gonna have 16 choices. The more I try and cram in, the more I will be able to talk about this person.

Stills from "I Can't Remember a Time I Didn't Need You."

You’re drawn to working in a lo-fi poly graphics style. Is that something that you’re still interested in moving forward?

Like a sketch, you can capture something about someone, and also, you can redo it. The style allows you to make iterations.

I like when the player uses their imagination to figure out exactly what’s going on. This low-poly aesthetic gives a sense of what’s happening, and then your brain can fill in the rest. For example, the fog in Silent Hill supposedly appears because there is evil in the town when the fog obscures your view—but actually, they couldn’t render the city as a whole, so they have to cover it.

Things like that for me create an incredible atmosphere. I’ve made a whole game that came from that fog, I Can’t Remember a Time I Didn’t Need you. That fog is so thick, consuming. It obscures, but you constantly think as you go down that maybe there is something hidden there.

When people were starting to make early graphics, it was just white men. They were exploring white men’s stuff. When I look at these things, I often see many missed opportunities to tell a narrative. I’m trying to think about what this thing could do in terms of a hard-hitting narrative and level structure.

Many indie developers see that as an opportunity. I’m interested in that low-storage, easily-pass-around-able file that has longevity. I’m interested in how something that can say a lot about someone can be stored in the smallest bit of data.

The sonic layering in BlackTransArchive creates this almost out-of-body experience. Were you thinking about the human voice as a way of continuing an archive?

Sound sews everything together. My process orbits around making “Praise trans music.” I want to make a song that feels uplifting for trans people and makes me feel good while singing here. I think, what do I want to talk about? I’ll write down three things. I press record and I’ll sing for five minutes. Whatever comes out of my mouth, I’ll sing over that again. Then I’ll sing over that, then I’ll sing it again. I’ll edit that, and then I’ll re-sing again. It’s the process of continually packing the layers again.

All I’m trying to do is capture what I’m trying to talk about. Maybe it’s the pain or feeling proud about being Black; maybe it’s thinking about privilege…I’m trying to capture the emotions around that moment.

It’s important to create a lot of data. Let’s say if I sang for five hours, I know only 20 seconds of it is probably going to be usable. It’s like when you’re painting, you try to capture this moment, and then suddenly something in the painting will work, and then you recognize, OK, I’m taking that out and expanding it.

I use a free version of the sound program FL Studio, which means that I cannot save anything. I have to make the track all in one go. That pressure is quite important to the work—you explore it, and when the program closes down on you, whatever is left is what you can use. Part of archiving is that you’re constantly losing things—trying to bring them back and replicate them. That frustration needs to be part of the process so that you can get closer to talking about these frustrations of the archive.

Using the free version of this music-making program—that’s what the crux is, is that you have limited time to make them. You don’t have stability around how long you can edit it for, so you better get it finished.

For perspective, I have 100,000 files on my desktop computer. That’s just the desktop! There’s just this constant outpouring of stuff. You may take a video 10 years ago, and it only becomes relevant now. I love to work in the 360—having enough things around you so that when the right time comes, you can take it and put it in your project.

You’re working on a game about piracy. What can you tell me about the process so far?

There was a particular kind of community agreement when you were on the ship. You agree to the community rules, and they’re different for every single ship depending on your capital. There were also Black ships—people trying to escape slavery or existing before slavery. Queer ships, too—all this kind of stuff that you don’t really get told about.

When you think of pirates, you think Captain Hook. But actually, pirates were trying to escape what it was to live in that particular system. I’m interested in this particular history of piracy—what it meant for colonialism, what it meant for the British rule.

What it would mean now to have a ship that could hold Black transness? What would you have below the cargo? What would you have on the deck? I’m currently creating a game where, based on the literal family ancestors who you have, you get to sail a particular ship. Your ancestry will determine if you’re allowed cargo or not; what kind of story will be told to you while you’re sailing on the ship? I’m really excited to tell the story of history through and on the sea.

Works in progress from Danielle.

Credits

Interview conducted in February 2021. Edited and condensed for clarity. Photography by Laura Vifer.