As retro-fetishism spreads, the search for more varied aesthetic guidelines intensifies. Most of the single-digit bits have been covered, as well as a fair spread of the 16 variety, and it’s only a matter of time before jaggy polygons are a visual device to be referenced rather than apologized for. This is a good thing: it forces us to more fully explore the true creative potential of what came and went so quickly.

DataJack, a self-described stealth/action/ cyberpunk adventure, dredges up a lot of library memories

One of those foregone areas of game design is the heyday of MS-DOS. I mostly played these in glorious VGA color at the library. Ah, the library! What an unsung repository for digital delights. Without the Laramie County Library, I never would have hunted down Carmen Sandiego, obliterated all the buffalo west of the Mississippi, or taken photos of creepy robots in the school hallway. These were the glory days of DOS for me, pseudo-cerebral mysteries that relied less on manual dexterity because the keyboard was a poor controller for anything resembling action, as old PC ports of Mega Man taught me. Pointing and clicking, with little instruction or imperative, was the style of the time.

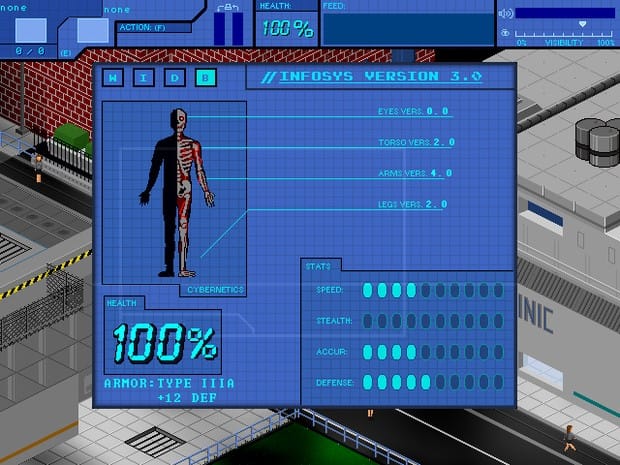

DataJack, a self-described stealth/action/cyberpunk adventure, dredges up a lot of library memories for me. (It’s available for free here.) Isometric 2D action undergirded with blue-screen-of-death style text frames the entire experience; the game combines the impetus behind Shadowrun with the hardware from Hackers. All the character portraits are straight MS Paint subway bombs, the gun icons lovingly crafted pixel-by-pixel, the stage maps part-Lego and part-diorama and loaded with sharp edges.

It’s also a bit of role-playing by default, inasmuch as there’s no initial story crafted for the player. Starting a new game lands you in your apartment, where your computer, shelf, and bed allow you the option of finding missions, organizing your stuff, or saving. You can go outside, where you’ll stumble across the usual assortment of shops for guns, hacks, computers, bio-enhancements, etc. But DataJack isn’t going to hold your hand and introduce you to the clerk. The stores are there for you to buy stuff, and the missions exist for you to complete them, and the motivation is that you started this game. It’s a throwback to an era when one was encouraged to click around until something changed.

The point of DataJack, not unlike Shadowrun, is to answer the call/email from these various shady anarchist groups and megacorps who are willing to pay to you to hack, steal, assassinate, and more. Anything for some credits, right? The emails you receive are colorful and entertaining, employing a Rockstar-like wit, but the bite is just a smidge sharper here. The actual missions give you various criteria to complete. But it’s in those missions that things get a bit hairy.

The game’s style is so firmly entrenched in the cathode ray tube era that it practically transports you there.

The key to working within an established aesthetic is to balance what worked with updating what didn’t. Its here that DataJack falls short, as simply walking around DataJack’s isometric world with the WASD keys is a trial, let alone trying to be stealthy within it. Shooting by mouse and planting C4 is accomplished easily enough, and weapons feel appropriately barbaric, since hacking and sneaking epitomize a job well done.

DataJack blooms from there, with customizable weapons, expandable hacking capabilities, 30 playable missions; everything but dialogue trees. This game is a fascinating (and still evolving) bedrock upon which expanded and fan-created content could grow. When I started playing, the lack of narrative impetus left me feeling unmotivated. But I would hunt Carmen like a dog without clear cause, so why not bash my way through DataJack? The game’s style is so firmly entrenched in the cathode ray tube era that it practically transports you there.