The Andes Flight Disaster of 1972 is infamous for the part about the cannibalism. On October 13th, a chartered Fairchild FH-227D crashed on the spine of the Andes between Chile and Argentina. A search was conducted for just over a week, leaving the team stranded. After two months of starvation, frostbite, and sickness, the Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571’s original 45 members had dwindled to 16, who all had to resort to eating the dead to survive. The survivors were all part of a rugby union, all Roman Catholic, and operated as a team: they salvaged together, they kept warm together, they starved. With the only qualified doctor dead from the crash, it fell to the medical student to fashion splints out of shrapnel from the aircraft. The Andes Crash is the definition of an extreme survival scenario.

It is impossible to discuss Dead of Winter: The Long Night without discussing the first Dead of Winter (2014). Plaid Hat Games’s Dead of Winter could be pitched as a “fun” tabletop survival scenario, if you enjoy The Walking Dead and the vote-down segments of Survivor and other reality TV series. In the game, a colony of survivors tries to survive the first winter of the zombie apocalypse: gathering food and supplies, killing encroaching zombies, and mitigating pressing crises. All the while, the group of players works toward resolving a larger game objective like, say, surviving a zombie horde or stockpiling supplies for the long winter. Each component—hunger, injury, overpopulation—creates a stress environment in which every decision carries some risk, and every risk promises some reward.

every decision carries some risk, and every risk promises some reward

Dead of Winter’s greatest strength is its hidden objectives, a mechanic heavily inspired by the Battlestar Galactica (2008) board game. At the start of the game, a number of objectives are drawn, shuffled, and dealt—most are harmless, some are malicious. The hypochondriac wants to help the group, but she needs extra medicine to win; the trigger-happy betrayer wants to bring the group down, but only if he’s stockpiled an arsenal. At any point, a player can be voted out by the majority and left to wander in the cold outside, but the group can never truly know if the exiled player was a betrayer or simply selfish until the end of the game.

Filmmaker Gonzalo Arijón—responsible for 2009 film Stranded: The Andes Plane Crash Survivors—said of the Andes Disaster survivors, “How did they manage to work together? Don’t forget they’re rugby players, and this is a game that requires a lot of group sacrifice . . . They managed to get out, as a group, with a system of rotating leadership, with no chief or leader being declared and no worker ants. The energy circulated.” This pull between individual want and collective need is at the heart of Dead of Winter. Players can hole up in the colony, but they’ll starve as the zombies pile up outside. If they leave to gather supplies, they brave the elements and risk instant death from a bite wound. Taking care of one’s own objectives can put the group at risk. And there’s always the haunting suspicion that one player might not be sharing enough supplies, that so-and-so might have sabotaged the crisis this turn.

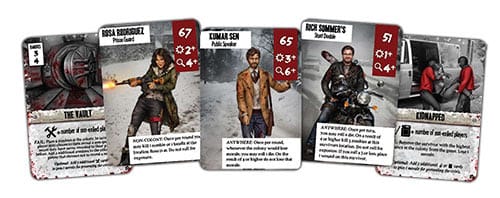

The game plays a lot of its excessive darkness off as a joke. If anything, Dead of Winter: The Long Night puts some of the subtextual farce of the first game into text. The original game’s food cans with their wry labels (“Refurbished Vegetables!”, “Zombie-Free Beans!”) have been replaced with hot pink Bloody Munchies cereal boxes (“They will revive you!”, “Whole Human Parts Guaranteed”). Although “replaced” is a misnomer: while all of The Long Night’s components can play a full game on their own, the box is an expansion. Beyond an array of new characters, crises, and story elements, The Long Night’s biggest additions come in the form of three new modules that slot into the original game’s stress-machine.

The first module allows survivors to fashion crude improvements to the colony, building turrets or fashioning a ramshackle clinic. The colony improvements cement the group survival mentality while softening the blow of the other two modules. In the second, the Raxxon Pharmaceutical company (a blatant homage to Resident Evil’s Umbrella Corporation) contains a pastiche of horror and zombie film monsters: werewolves, creepy little girls, even a riff on Nightmare on Elm Street’s Freddy Krueger. While silly in appearance, the Raxxon sideshow pushes the group to constantly seal its doors every turn, and that’s in addition to the regular challenges of the game, or else the nightmarish creatures will escape and wreak havoc.

a fully-functional Walking Dead-esque war of colonies

It’s important to note that, while the incident is known as the Andes Flight Disaster in English, the tragedy was popularly referred to as El Milagro de los Andes (The Miracle of the Andes) in Spanish. The horrifying acts of cannibalism were likened unto the rite of Communion, in which believers symbolically eat the flesh and blood of Christ. Survivor Nando Parrado wrote in Miracle of the Andes: “I didn’t know how to explain . . . there was no glory in those mountains. It was all ugliness and fear and desperation, and the obscenity of watching so many people die. Shortly after our rescue, officials of the Catholic Church announced that . . . we had committed no sin by eating the flesh of the dead . . . [T]hey told the world that the sin would have been to allow ourselves to die.”

But what if the binary is changed from survival vs death to our survival vs theirs? The Long Night’s third module introduces a hideout of bandits, which brings the game closest to playing out like a segment of Walking Dead and The Last of Us (2013). Adding this module introduces an automated colony of competing raiders who scavenge and draw zombies out to their locations on their own. The bandits don’t simply add an additional pressure point like the Raxxon module: they bleed into the map and seep into the colony (the module’s token scenario even includes a bandit betrayer who has to “play along” with the group to win). The bandit module is a step toward what players are asking for: a fully-functional Walking Dead-esque war of colonies between players. And that’s essentially what The Long Night is—giving players more of what they already want.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.