DEIOS, glitches and the death of videogames

You are firing a gun. It is not working. It is working but barely: it is flying over some man’s head even though you are shooting it directly at him. Sorry: you are shooting it at Him; that man is God. The gun takes 20 seconds to reload. It is probably the worst gun you’ve ever used in a videogame and it could not hit the broadside of a barn, or, to be more specific, the frontside of a God who is twice your size. This gun is awful. God comes near you. You are now dead. You look for a new gun.

You are playing DEIOS. You are having a “good” time.

///

Mostly what I remember from college, besides a handful of embarrassing sexual encounters and the years in which the Crimean War took place, is the general surplus of noise. I did my best to contribute to it. Somebody, after all, is the guy who is too loud, and that was me, pretty much all of the time. I tried to set my stereo such that I could still discern individual lyrics in the dorm’s shower; I considered this a community service. I imposed that month’s tastes on every roommate like so much body odor. If I needed to house a party I ensured that it was one in which people spent most of their time screaming at each other. I broke one stereo my freshman year and another my junior year. I regret none of this.

Going to a state university in the Midwest known for a) alcohol and b) setting things on fire has the ability to uniquely prime one for a surplus of sound. Where there was not Me, Maker of Sound (TM) there were others like me, making sounds, everywhere. In that capacity I must’ve fit in well but in no other manner did I feel normal. There were bars of fraternity brothers screaming and vomiting on sorority sisters in their time-honored way; there were braying hippies on megaphones eating bagels or whatever; there were thudding, shuddering clubs filled with sobbing human beings and where I swear I once saw a man and woman have sex on a stage as people took photos. It was disgusting. I sort of hated college, which is probably why I made so much goddamn noise when I was there.

Where there was not Me, Maker of Sound (TM) there were others like me.

Anyway, I was lucky my freshman year to fall in with a crowd for whom noise was not something passive but instead an active vocation. I’m not sure what sort of trajectory these people had taken to get to this place but they spent most of their time either listening to or creating mountainous walls of sound. There were variations on the theme–feedback with metronomic drums, feedback with another person playing keyboards, keyboards that sounded like feedback, a broken Teddy Ruxbin farting into a microphone, and so on. I treated these people, the only people louder than me, the loudest people I could find, as a sort of salve. I didn’t really have to say anything around them, which was fine; there was nothing to be said. What would our voices do anyway amidst the din?

///

I’ve been thinking about noise a lot lately because me and a few other writers recently read the great and totally disagreeable A Theory of Play by Raph Koster. His general aesthetic theory is (spoiler alert) so formalist and system-based that you are sort of forced, constantly, to be arguing against the author, sniffing out things that don’t fit into his all-encompassing theory. Within our ever-present desire to create and perceive order, videogames, he says, provide us with “exceptionally tasty patterns to eat up,” just as books offer variations within the rules of grammar, music within scales, cinema through lenses, and so on. In games we are taught a system and then experience the delight of practicing that system. I spent most of the book wanting him to acknowledge the outliers, the system-breakers, and at one point he does, sort of:

“Noise is any pattern we don’t understand. Even static has patterns to it. … There’s really next to nothing in the visible universe that is patternless. If we perceive something as noise, it’s most likely a failure in ourselves, not a failure in the universe.”

This complete punt–”noise isn’t noise, actually”–is so slyly unsatisfying it wasn’t until I was done with the book that I realized what was missing. Raph would probably have an answer for my dissatisfaction; Raph, you get the feeling, has thought this all through. You get the feeling that Raph quietly burns any sock he can’t match. The point of noise is not to be completely patternless and ungraspable; the point is to try to be. It’s to make the earnest human effort to abrade despite all the impulses in our brains seeking like comfort, soup, Fleet Foxes.

Still, I sigh: Raph’s got a point, at least in terms of videogames. It is an orderly artform, by and large. We are often eating soup, feeling comfortable, creating order.

The clearest expression of noise in a videogame isn’t even design: it’s accidental. Glitches are the raw, screeching feedback of digital play. It’s the machine breaking and contributing something that neither the artist nor the audience intended. This is why it’s so imperative to drop everything except the controller and explore when a glitch rips open a game you are playing. Like the ear in the field at the beginning of Blue Velvet, it can lead anywhere. Only in art can we take that journey safely. The other night a friend and I spent twenty minutes in the wonderfully stupid Need for Speed: Rivals driving up some hill at a walled-off construction site, scraping our way around its embankments like a horse up a mountain in Skyrim. Sparks, lens flare, and camera pulls continued apace, as if we were barreling down the highway and not leaning horizontally against a tree, spinning upward. Eventually the game jerked to attention, remembered its manners, and flopped us back on the road. We sighed and accelerated.

///

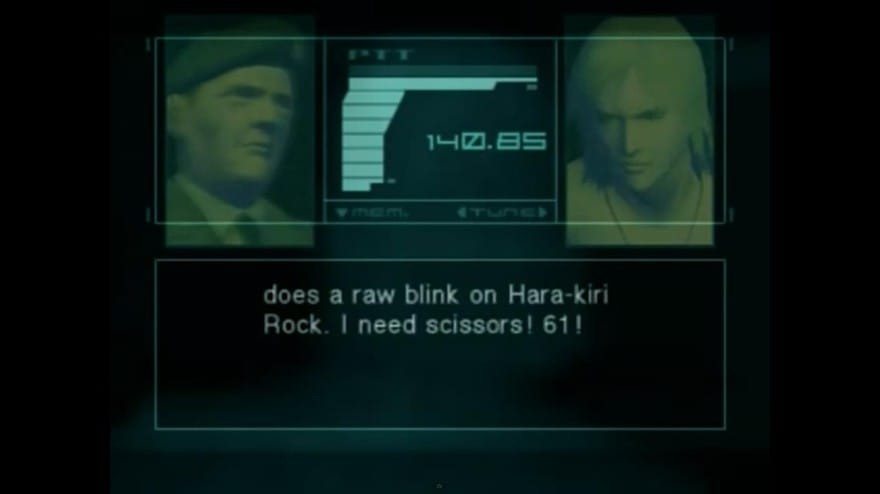

DEIOS is probably a step in the wrong direction, by which I mean the right one. It is a game of almost luscious inscrutability. In it you play as a tiny man who assembles a gun from over a thousand variations in order to take on a sequence of gods in a large arena; almost all of these guns are terrible for one reason or another. You’ll flail your little mouse around, trying to get a bead on one of these enemies, and then die. Then you’ll assemble a new gun, trying to find a variation less statistically awful than the others, and head out there to die again. Much of the fun of the game is in this reassembly process, and in the realization, eventually, that that gun doesn’t matter; that the game’s brokenness is in fact its way forward. I believe it was made by a 19-year-old, and it shows; not in any sort of lack of craftsmanship (it’s visually stunning) but in its unchecked rush of angry ideas. “Conways Game of Life Is Proof of No God” it informs you in an early, tone-setting flash.

The point, though, is that DEIOS is obsessed with failure. Your failure, which will be repeated and unfair, is almost beside the point: the whole game is fucking up, coming apart at the seams. Its screen is a mess of film grain, cigarette marks, overlaid textures, palette swaps, and blurs; its sound design splits the difference between a sort of meticulous electronic wonderland and an 80’s action movie soundtrack played at variable speed. At certain points the game just layers several tracks over one another, in a filthy, shimmering wash, but you have been primed for what-fucking-ever; it sounds fine. The record player is wobbling, the projector is old, and the videogame cartridge is loaded with dust. The room smells like urine and the sound of someone vomiting doesn’t turn a head.

Glitches are the raw, screeching feedback of digital play.

There have been a rash of these battered, bleeding games lately. Vlambeer’s Glitchhiker and Farbs’ Rom Check Fail wear the glitch as sprightly fashion, sending you out on a quick-hit hunt for a high score amidst a field of temporal tears. Fjords, as well as the upcoming Quadrilateral Cowboy and Glitchspace, send the player foraging through code, giving them the keys to the kingdom but showing them, slowly, the consequences of that power. Memories of a Broken Dimension casts a more Lynchian pall, focusing on the glitch not as a means to an end but as a symptom of some sort of greater, almost ontological emptiness.

It’d be stupid to create schools of these games, inchoate as the idea is, but if anywhere, slot DEIOS alongside Memories of a Broken Dimension. It’s in the business of raising questions. DEIOS‘ interstitial text insists upon the act of videogame creation as a godly one—it is, after all, the creation of a universe—which makes the quest to kill god and the exploitation of a glitch analogous. Both are acts of righteously Satanic defiance. (It’s this forcefulness that feels so 19-year-old.) What’s interesting about DEIOS, though, is that one can watch it become broken, if so inclined. A demo version, released in the middle of last year, suffered from the paucity of ideas of many art games: you sort of go to a place to see more pretty things, then go to another one. But it was a decidedly more whole, giving experience. One walked to the right; one entered doors; one fought a boss. In its final incarnation it has moved from this laissez faire attitude to a design that’s clenched as tight as a duck’s asshole.

And here’s the thing: it’s fucking impossible now. I’m not sure I would recommend it to anyone but for the fact that alongside its increase in difficulty it got significantly more beautiful over time. I found its creator’s email online and sent him a note like “Is it really like this?” (since early versions of the game were, appropriately enough, malfunctioning on Windows 8). He sent me back a YouTube clip of Bruce Lee. It’s really like this, in other words. Life is hard. Death is easy.

///

To be clear: noise music is the worst. The amount of time I have spent in my life listening to noise music since college is roughly 0.000%. I have gone to noise shows in my post-collegiate life a couple times and watched people bob their heads intensely to sound with no rhythm, almost as if in competition to see who can find some sort of sequence, all of which you sort of have to do because noise musicians are the most serious motherfuckers on the planet. There is apparently nothing funny about the fact that you are listening to a bunch of machines malfunction for four hours. You will stand there with your cigarette and you will smoke another. And you will nod.

It seemed funny in college. We made fun of the fact that we were spending our time doing this in the same way that we’d make fun of Aspen Extreme on VHS later that night. The only reason I think I fell in with this crowd is that for some reason there were a lot of people doing it at my college at that time. Weird cultures occasionally just sort of happen and this was one of the weirdest I’ve ever seen; I existed on its periphery and haunted the single dank bar and the handful of basements that housed it a couple times per month, each time leaving as the sun went up as if I’d never not been there and smelling like beer and sweat and our ears buzzing so loudly that we couldn’t hear what we were yelling in each other’s ears.

Which is what was missing whenever I looked in on the “professional noise circuit” after college. Not the volume; the fun. You almost wished that there was a sense of, I dunno, play about the whole thing.

///

The thing about a truly noisy videogame like DEIOS, and anything that comes along in its colorful wake, is that it’s not something you enjoy passively. You can just sort of endure a noise record; you can put it on while you leaf through Feedly and you can head into your afternoon the same person. But a videogame requires _you_. It requires you to actively not have fun. (Somewhere Raph Koster is clucking with approval at my word choice.) In a noisy videogame you aren’t just nodding your head in strange competition; no, in a videogame you are on stage playing the keyboards. You are the serious motherfucker. You have a thousand cigarettes.

But for all DEIOS‘ beauty, and all its strange anger, it’s a flashing arrow in the right direction. It’s the applied noise that gets things done, anyway; it’s noisiness. It’s the bird people soaring across the sky and the pitch that never quite coalesces, the actively rupturing vocal chords and the radio freakout. It’s chaos within a structure and it’s structure gone to shit.

I have no idea if someone will plumb the depths and deliver into our hard drives a creation of such pure, calcified shit. Such a game would probably be awful. True noise got off in earnest when Lou Reed released Metal Machine Music in 1975, a double-LP set of ululating feedback, but there hasn’t been an equivalent in videogames. Developers are circling the idea right now like vultures around a starving mule, heaving through its ribs. The thing to keep in mind is that when Metal Machine Music came out, no one could figure out whether or not the whole thing was just some sort of joke. Reed never really let on, one way or the other.

First inline image via J E Theriot