Democracy 3: Electioneering is a misguided publicity stunt

In his 1989 essay “The End of History?,” the political scientist Francis Fukuyama, engorged by the collapse of the Soviet Union, claimed that human civilization had reached the conclusion of its sociopolitical development. “What we may be witnessing,” he writes in summary,“is the endpoint of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” When later pressed for examples of what post-historical governance might look like, Fukuyama generally pointed to the example of the European Union, a supranational entity inspired (in his view) by an attempt to transcend national sovereignty, a defining characteristic of his post-historical world.

The ‘inevitable,’ though, has a way of unravelling in spectacular ways. Fukuyama’s post-Cold War optimism has been looking rather jejune lately, as liberal democracies across the West have found themselves strangled by a resurgent nativism that has helped spawn, among other iniquities, Trumpism, Norbert “Put Austria First” Hofer, the Brexit, France’s far-right National Front, and… need I go on? Arrange those embarrassments alongside the failures of the nominally pro-democracy Arab Spring and Orange Revolution, to say nothing of the abuses committed by the democratically-elected governments of Thailand and Turkey and, well, Fukuyama’s democratically-centered vision of the ‘end of history’ is looking tenuous indeed.

what does it even mean to represent democracy in/as a videogame?

So when I receive an email inviting me to review British studio Positech Games’ Democracy 3: Electioneering that opens with the question, “With all the political madness currently engulfing us, isn’t it time for some clear direction?,” I am almost at a loss for words. Isn’t the problem not that we’re lacking a clear direction, but that the direction towards which liberal democracies are tilting is all too clear? And, more importantly, that this all-too-clear direction is a fucking nightmare? A game designed to simulate the operations of a functioning (or not) democracy is going to be politically charged even under the most copacetic of historical circumstances. But at a moment when many on the left, myself included, have never felt more hopeless about the future 2016 augurs, what does it even mean to represent democracy in/as a videogame?

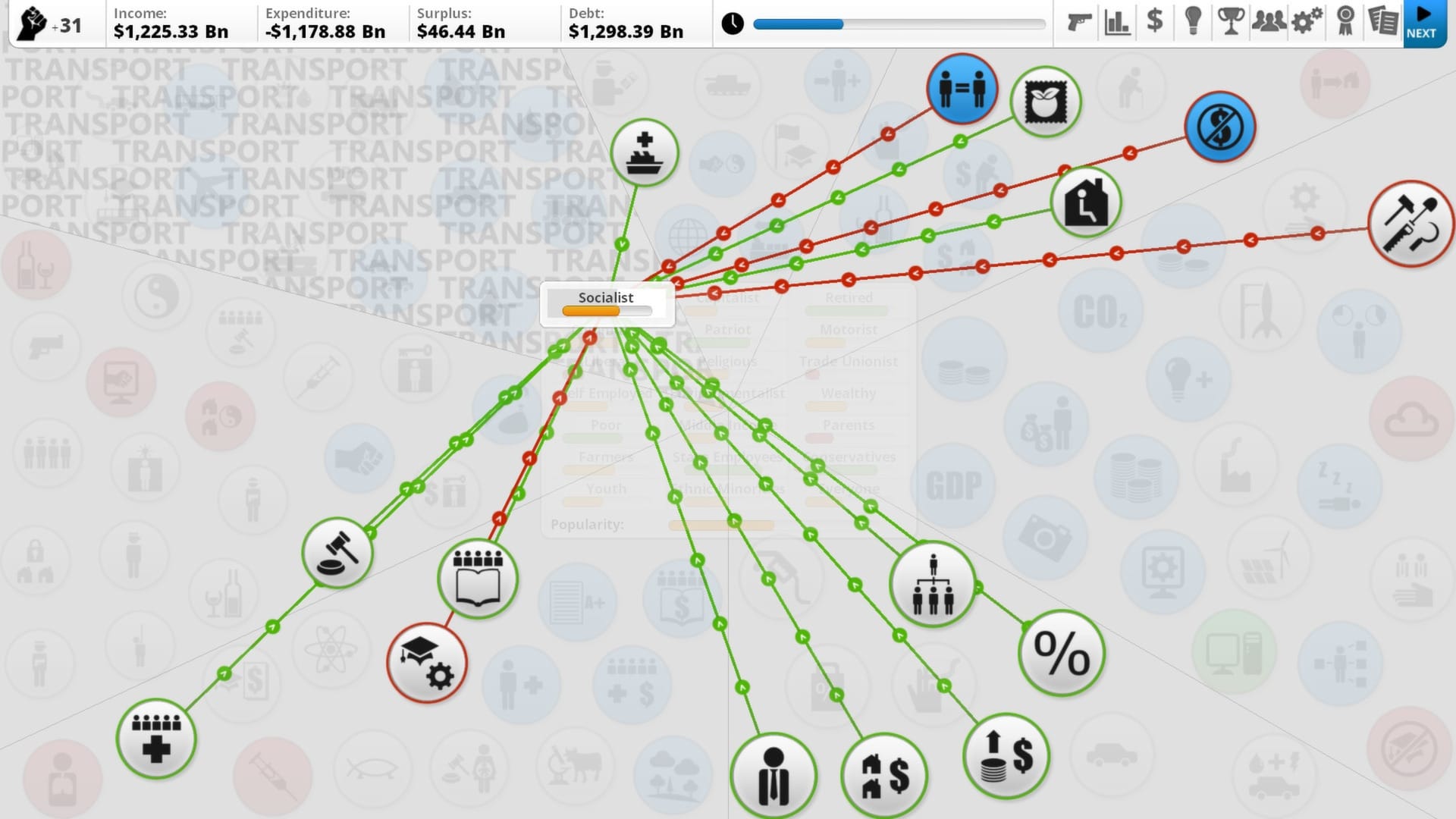

The original Democracy 3 (2013) was an impassioned procedural argument for incrementalism, the belief that political change is best enacted through an ongoing series of small adjustments. Success in the game—defined as the ability to realize your political ambitions, whatever their ideological bent, by raising and expending political capital in favorable ratios—was entirely the province of compromise. Democracy 3’s iconic, elegant interface is an array of bubbles representing particular policies connected by pulsating red and green arrows, which indicate the force policies exert on popular opinion. This interface forced players to acknowledge that this was no opportunity for moral certitude. Once, when faced with a scientifically illiterate and globally uncompetitive workforce, the only practicable way for me to ban mind-dulling creationism from schools without losing reelection (or worse) was to restrict access to abortion.

Unnerving though it is, there is a begrudging kind of truth to this argument: democratically elected politicians can rarely afford to be the face of anything but the most moderate changes without risking the very platform that enables them to enact change in the first place. Democracy 3, in this sense, suggested 1) that the continual recalibrations politicians make is not a weakness of liberal democracies, but a condition of their existence, and 2) that compromise, in both its moral and practical dimensions, is part of the price we pay for the ability to elect our leaders (see Kill Screen’s David Rudin for more on the game design of democracy). To be sure, this view represents a particular way of thinking about democracy, but it is also very hard to discount without ceding any claim to an actionable platform.

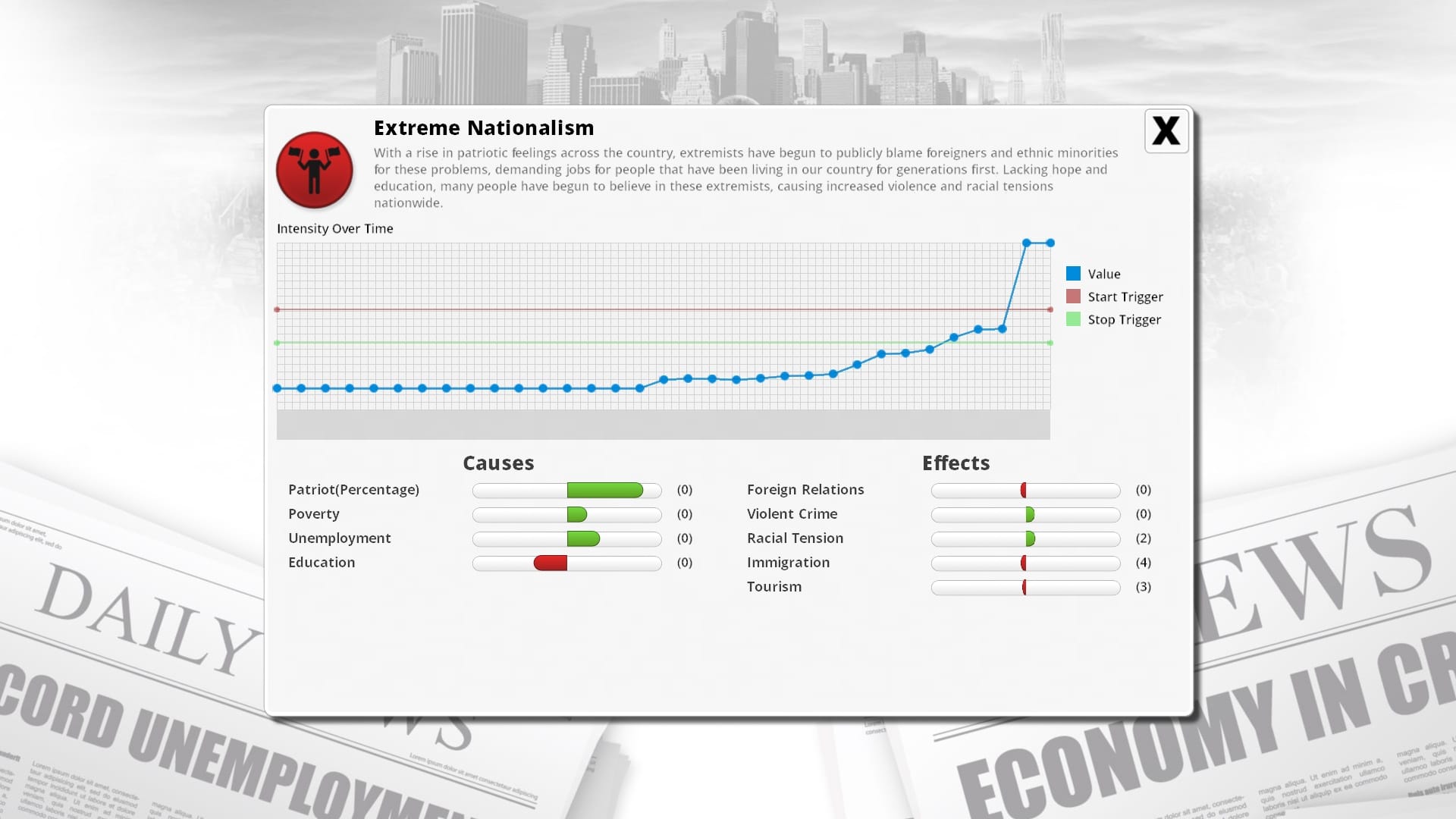

Electioneering is Democracy 3’s fourth expansion, but with the notable exception of Drones and Clones (2015), a surprisingly thoughtful speculative fiction on the fate of policy in an age of automated economies and bioinformatic surveillance, Positech has largely turned its attention to the complicated (and complicating) minutiae of liberal democracies. Social Engineering (2014) focused on micro-policies—think widened bicycle lanes rather than rent-controlled housing—while Extremism (2014) enabled policies beyond what a congressperson may mention in public (from Extremism’s press release: “For when fiddling with tax rates isn’t enough!”).

“politics is theater; it doesn’t matter if you win”

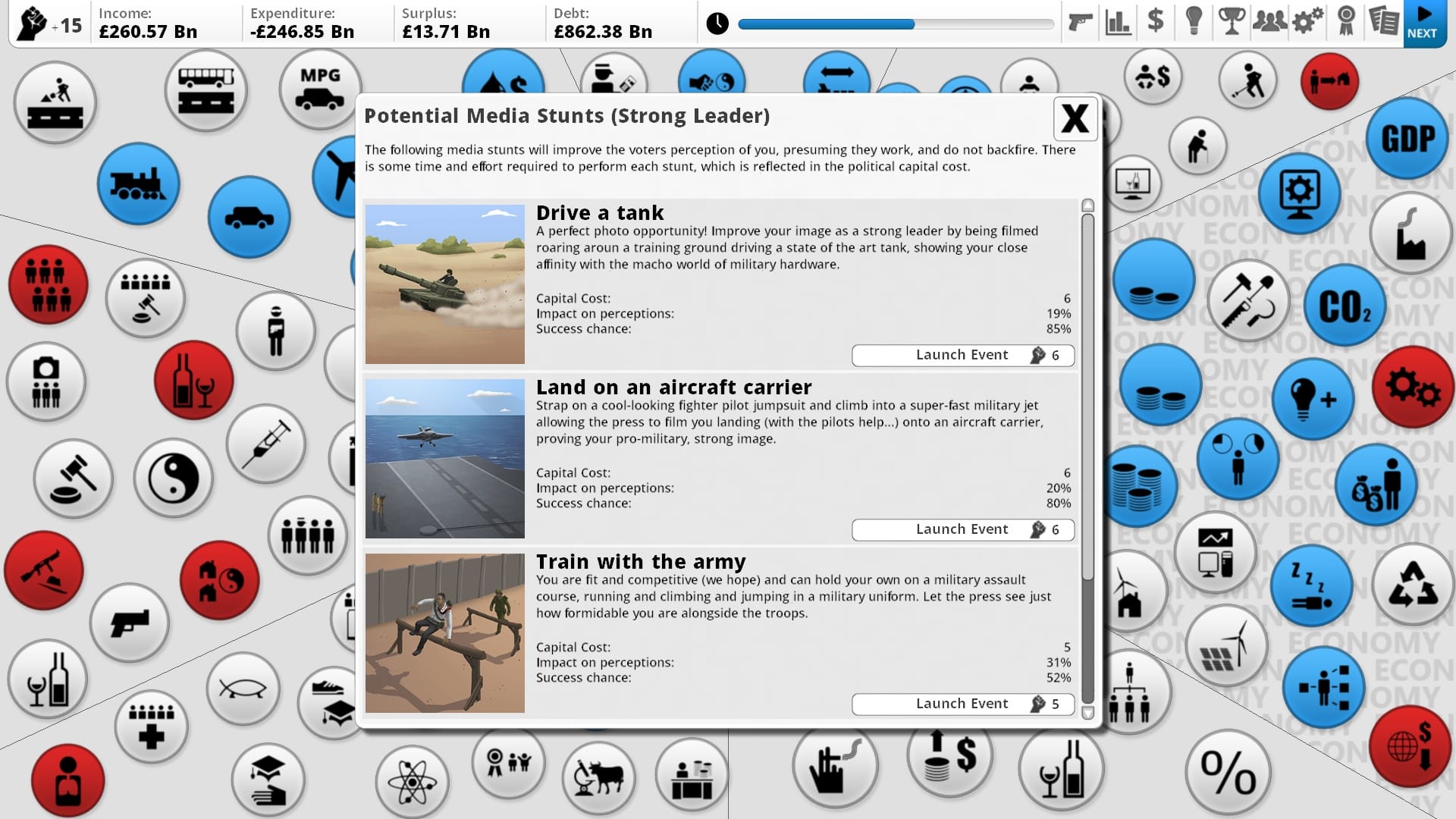

The purview of Electioneering is the public ritual of the election and the forms of rhetoric that it constitutes and is constituted by. There are no new policies upon which to ruminate, but there are publicity stunts and speeches and manifestos and focus groups and grassroots organization and donors galore! Above all, Electioneering is attuned (and committed to) the artificiality of political communication as a continually calculated performance. When Harvey Milk said “politics is theater; it doesn’t matter if you win,” he wasn’t wrong. Neither, for that matter, was Paul Ryan when he dismissed congressional Democrats’ recent sit-in for gun control as “political theater.” Of course it was theater. What protest isn’t? Electioneering, though, exaggerates these practices into the political theater of the absurd; why pose on an aircraft carrier when you can land a goddamn fighter jet yourself for a 20 percent boost in public perception at the low cost of six units of political capital?

And, look, there’s still something to this. When we mock political communication for its blatant lack of “authenticity” (whatever that is), we’re diverting attention away from why it’s “inauthentic”—which is that it’s the rhetorical appeal to which people have responded most. And it’s a whole lot easier to scapegoat the public performance of politics, a performance whose purpose is always known in advance, than it is to admit the collective failures that set the conditions and causes of that performance. Electioneering, in its way, reminds us that it makes little sense to solely blame politicians for their mode of speech when it is a carefully constructed mirror of the electorate’s imaginaire. And perhaps, in that sense, the ritual of election is working exactly as intended (one of The Onion’s best headlines once made this very point: “Petty, Shortsighted Americans Outraged by Legislature that Represents them Perfectly”). But is this a problem inherent to democracy? Or is it a problem with people? And is it really so wise to separate the two?

I don’t have answers to those questions—I really don’t—but what I do know is that somewhere between the release of Democracy 3 and Electioneering, Positech got a lot more sardonic about the whole endeavor of government by the people, for the people. Regrettably, the veneer of irony that covers Electioneering isn’t always flattering; Democracy 3 was never a game for idealists, but it did appear to celebrate, however tentatively and naïvely, the liberal democracy in spite of—and maybe even because of—its faults. Democracy 3 assumed, I think, that there is still some distance between cynicism and pragmatism, and that there is value in learning to live with the contradictions of democracy as we practice it today.

But Electioneering imagines democracy as if cynicism and pragmatism were the same thing. What’s at stake when we don’t think that distinction matters? I keep coming back to that request for a review and its maddening opening line: “With all the political madness currently engulfing us, isn’t it time for some clear direction?” Democracy 3 makes no claims about what “direction” is best; it is a game of effects, not of judgements. To wit, the game offers achievements for bringing into being societies as dissimilar and objectionable as technolibertarian dystopias to conservative theocracies. But, as far as I can see, the only “clear direction” Democracy 3 praises, the only feasible principle upon which to build a society, is the prime directive of incrementalism.

incrementalism is not a virtue; it’s a tactic, and not an especially virtuous one at that

Fine. So be it. But incrementalism is not a virtue; it’s a tactic, and not an especially virtuous one at that. When we lose the ability to distinguish the two, incrementalism quickly becomes something praised only for its own sake. And here’s the problem with that: not everyone can wait for change in increments—such a belief belongs solely to the privileged, those whom the status quo already serves. And so, in its tautological form, incrementalism ends up perpetuating the very inequalities it once sought to remedy. Is this the ideological statement Democracy 3 has been trying to make all along? Or are we simply witness to the failure of its designers’ political imaginations?

The latter, I think. Democracy 3 and its expansions offer very few ways of thinking about political change beyond familiar democratic avenues. Even the most radical ideas in Extremism are still firmly couched in the language of policy. What’s more, I think we should be very skeptical of any game that equates a punitive wealth tax with extremism. If that’s Democracy 3’s idea of “radical policy,” what would it make of the forceful seizure of the means of production? Or, for that matter, any form of political action outside of a narrow band of policies that, if not necessarily neoliberal-friendly, exist only in relationship to neoliberalism?

That’s not to say that Democracy 3 is devoid of direct political action; it’s just that direct action is something exclusively done to, not by, the player. One of the most-discussed aspects of the game is its fail states: the game ends either when you lose an election, or you get assassinated (!). And because it’s not particularly difficult to be reelected in perpetuity, the only real threat to the player is getting murdered by ideological zealots, and the only way to rouse the ire of ideological zealots is to enact widespread social change too quickly. Example: buoyed by the example of Switzerland, I attempted to implement something approaching a universal basic income for my citizens, a policy, mind you, that’s often praised as a compromise between the left and the right’s respective beliefs on how to grapple with poverty. But despite several pandering speeches intended to soothe the egos of free market fanatics, my plan resulted only in my ignominious assassination at the hands of some “well-funded capitalists.”

There’s a frustratingly low ceiling to the expressiveness of Democracy 3’s ruleset that’s particularly limiting when it comes to imagining alternative forms of political engagement. And that’s a major problem because the fundamental questions a game like Democracy 3 provokes— eternal questions about the balance of pragmatism and idealism, or the inability of democracies to ensure the same quality of freedom for all their citizens, etc.—are not questions whose answers can simply be found, but must literally be worked out. Because it may well be that, after a long debate, we collectively—or, if you prefer, democratically—come to the conclusion that a commitment to incremental change, despite its many limitations and risks and inequalities, is the only reliable tactic we have to move toward a more perfect union. Or maybe not! The point is that it’s a conclusion to be arrived at only through a consideration of every other possibility, the very possibilities Democracy 3’s mechanics are incapable of exploring, limiting us only to whatever exists within the event horizon of incrementalism.

There’s a frustratingly low ceiling to the expressiveness of Democracy 3’s ruleset

But there’s something even more sinister in Democracy 3’s dogmatic praise for the increment. No matter if you wish to do “good” or “ill” in Democracy 3, and regardless of what you think those terms signify, you can only do it slowly. And that, I think, is where the game falls short the most, in its belief that democracy can manage the “good” and “ill” in equal measure, that incrementalism is somehow symmetrical. But just as words are imbued with a greater power to harm than heal, liberal democracies, by design—game design—have recently shown themselves to be a lot more capable of damaging themselves than finding ways of repairing that damage. Democracy gave us the Brexit, but it’s hard to see how it can now save us from its consequences. In the United States, only 13 million people—about four percent of the population—have so far voted for Trump, but the visibility of the candidate will ensure Trumpism persists long after November, just as the student riots of May ‘68 helped depose Charles du Gaulle, but renewed Gaullism’s lease on French society.

None of this is to say, of course, that democracy isn’t a net positive; all things considered, I genuinely believe the ability to elect our leaders should be counted among human civilization’s better achievements. But Democracy 3 is an object lesson in the dangers of taking the liberal democracy as an incontestable ontology; this uncritical view prevents us from seeing and doing something about the faults that have, in time, emerged from its noble design. This was, after all, what an optimistic Fukuyama didn’t perceive when he wrote “The End of History?,” as the Berlin Wall came down and Turkey began petitioning to join the European Union. I’m sure the triumph of Western liberal democracy did have a certain air of inevitability in those halcyon days. But Fukuyama’s imagined threats to democracy, past and present, were all exterior (even today, Fukuyama believes the only credible threat to liberal democracy is Islamic extremism). It’s that kind assuredness that prevents us from seeing how our chosen form of political organization contains within it the means of its dissolution. And so, Democracy 3, like Fukuyama’s boldest claim, ends up withering in the harsh light given off of whatever histories are being made.