Can Devine Lu Linvega create his own language? Or a new world?

Devine Lu Linvega, whose game Nataniev was released last week, has the rare perceptual condition known as synesthesia. This, amazingly, allows him to see sound, and vice versa. He tells me the condition is not what I think it is, that it’s not some grand beatific vision, that it has nothing to do with universal oneness, that it’s not psychedelic, as is often claimed. It’s more subtle than that. He compares it to being reminded of a long-forgotten dream that you can suddenly see clear as day. It can be triggered by a sound as simple as running water, or listening to William Basinski on headphones. His way of describing it could be misattributed to Proust. “It’s like having a memory of something you’ve never experienced,” he explains.

Linvega is using his invented language as a sturdy foothold to logically descend into the impossible.

Though not too many of us can hear colors, it’s easy to relate to his sense of disconnectedness. As the MIT professor Sherry Turkle wrote of in her book Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, our love affairs with devices have undermined something human in us. Children are often more attached to My Real Baby than their real baby sister. Texting saves us the hassle of voicemail, but deprives us of the human voice. Modern ways of staying in the loop frequently feel distant.

Granted, Linvega’s case is an extreme one. A child of the internet era, Linvega is slim, slightly wan, and wears thinly-framed glasses. His figure is all angles, symmetrical to a T, like a sinister Jimmy Fallon. A tattoo peeks onto his neck. The indigo ink-work is of three circles arranged in a triangle around his Adam’s apple, as if his face is a code to be deciphered.

That’s just on the outside. Within, his mind is brimming with obscure ideas about the hanged man tarot, the mythic city Agartha (located below the Earth’s mantle), symbology and pedometers. His app Nataniev is an exploration of Mark Twain’s unfinished novel The Mysterious Stranger, which follows the exploits of a Satan who’s day-tripping from hell. “How does it feel to wander around something that is lively but to your eyes just looks like mud?” he thinks aloud. Keep in mind, he’s talking about a demonic walking app.

A youthful Aleister Crowley…

It seems detachment has penetrated every facet of Linvega’s imagination, from his visions of unreal places to the isolate mood prevalent throughout his games. The name of his previous game ‘Hiversaires’ is French, loosely translating to ‘the ones who come from winter.’ This could be an analogy for Linvega himself. A French Canadian with a love for Japan’s club scene, soba, and its warmer climate, he relocated from his home in Montreal to Tokyo.

But within weeks, Linvega was already shaking from culture shock, a feeling that he captures well in the dystopian recesses of Hiversaires. “[The game] is my vision of Tokyo. It’s how I feel about living here,” he tells me in ginger English as we talk from across the ocean over Skype. His voice sounds conflicted, as if he’s no longer sure how to relate to the country he once adored.

Linvega, who’s a web designer by trade, was employed at a web development firm when he became dispirited with the notorious labor practices of Japan. “You have to go drink [with the company] on Friday,” he says. “At first glance, everything’s great. Then, you realize you’re there because your boss is so depressed from work that he has to drink away his sadness.” His superior was in a destructive tail spin, “trying to forget why he hadn’t seen his family in two weeks, why he’d been sleeping under his desk,” he says. Finding himself increasingly distressed, Linvega packed and quit.

“It’s like having a memory of something you’ve never experienced.”

But Tokyo is an expensive city. He was in need of yen. Linvega came up with the idea to make several games that he could sell on the App Store to help cover rent. Two months later, Hiversaires was born. Linvega did all the work on it himself. He illustrated it, composed it, designed it, and coded it. The end result was a playable portrait of the way he envisions living in Japan.

The setting is sterile, motionless, largely empty—an abandoned facility intertwined with electrical tubing, circuit breakers, and capacitors. Though the cryptic puzzles are somewhat reminiscent of those from the classic adventure game Myst, the game’s grayscale corridors and mothballed machinery have more in common with Solaris, La Jatee, and the short stories of Jorge Borges. They cause you become lost in uncertainty. These claustrophobic halls can truly make one feel like Monica Vitti in a Michelangelo Antonioni film.

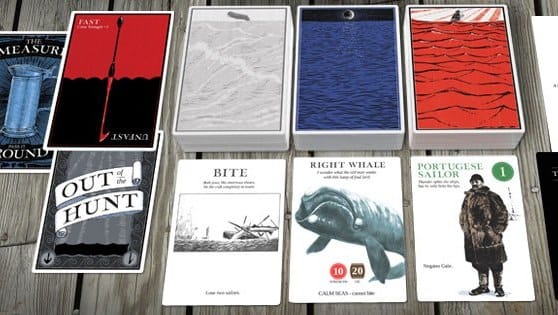

To make matters worse, the game world is littered with arcane symbols that belong to a language Linvega invented himself. The asymmetric shapes are equal part alienating and fascinating. They clearly mean something, but you’re clueless as to what. You can compare this to Linvega’s situation in Japan; he doesn’t know the language that well. But the mysteries of Hiversaires may be more daunting. Linvega tells me that his symbols correspond to the deck of tarot; that there’s a message in the first room which means ‘looking into the future’; that there’s a very good reason you’re pushing all these buttons. Part of it is doubtlessly that occultism helps him cope.

“How does it feel to wander around something that is lively but to your eyes just looks like mud?”

Like a youthful Aleister Crowley, Linvega has dabbled in arcana as a hobby since he was fifteen. “I was wondering what the ideal language would look like or sound like,” he says, explaining how some languages are simply better suited for expression than others. Whichever one is the best, it’s probably not his native French. Of late, he’s been trying to simplify its rules of grammar. Also, he’s looking into Isaac Newton’s unfinished universal language. “I’m trying to complete his notes,” he says.

As for the sigils in Nataniev and Hiversaires, they’re not that great at describing physical things. They’re better at “explaining ideas… abstract thoughts… dreams…,” he explains. That means they’re perfect for conveying the illusory locales of his secluded worlds, which he refers to as “impossible space.” If you try to draw the layout of the game, “you’ll realize [nothing] makes sense,” he says.

It seems Linvega is using his invented language as a sturdy foothold to logically descend into the impossible. But if the symbols trail off in patterns to someplace magical and elusive, and the roadmap is so twistingly intricate that no one can follow him, Linvega could vanish into a maze of his own doing. Grappling with the estranged reality of cultural displacement could lead him to solitary lockdown.

But perhaps detachment isn’t so bad. After all, he has an entire universe to himself. During our conversation, he pointed me to a page on his website. (The page has since disappeared. His site seems constantly in flux, different each time I’ve visited.) There were about ten or fifteen symbols—his own solar system plotted out in a spatter of esoteric marks. There was the symbol for Leteot, the planet on which Hiversaires occurs. Then, he pointed out the symbol for Killion, a small moon of Leteot, where his new game Nataniev is set.

“It’s so beautiful!” he says of the star. “It’s where Satan goes when he tires of Earth.” Later, he shot me an image over the computer. I thought it looked like a torii, the ancient Japanese gates found at the entrances to Shinto shrines, standing auspiciously in the distance. But it wasn’t. It was the glyph that connects the isolation of Leteot to Killion and Nataniev in all its beauty. It was his escape route.