Content warning: This article mentions child abuse and rape

///

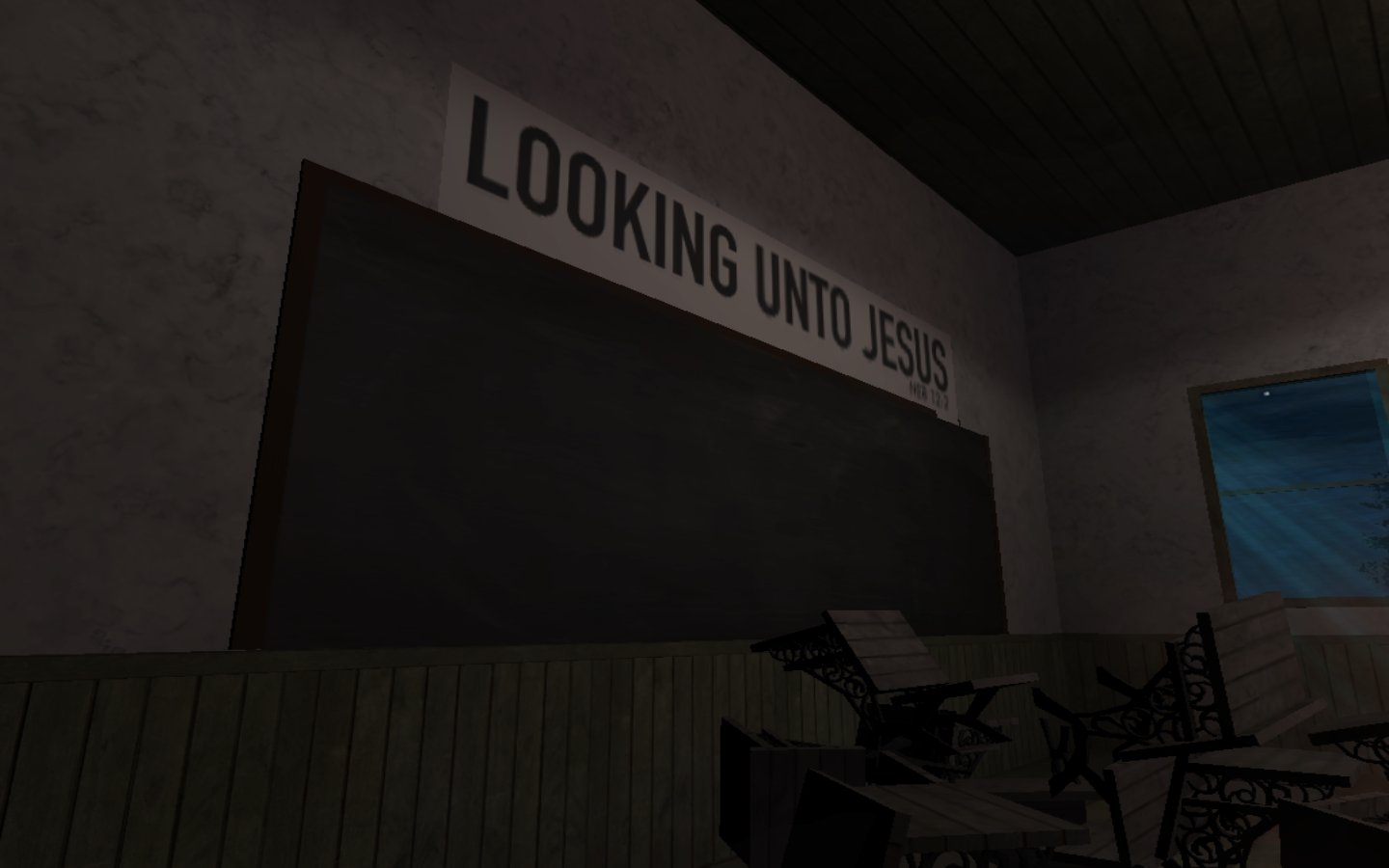

The Raven and the Light (2015) starts with a car crash. It ends with an almost dream-like ascent to a state of transcendence, narrated by the myth of the raven and the light—a Northwest indigenous folk tale. Everything in between thrusts you into a world that, for some, will be foreign, but for North America’s indigenous population is and has been painfully real.

Your character in this horror game (mostly unseen and unheard throughout) explores a fictional residential school called Mother Mary’s Residential School for Indian Students. Inside, you dodge monsters and creatures while picking up documents (letters, diary entries, and records—also fictional) that tell the story of a former residential school student—referred to as Sixty-Four—who was raped by Reverend Caldwell (the clerical patriarch of the school), who is later revealed to to be your mother.

Its invented details might not be real but the horror of the experience is

Not many videogames would dare venture into a subject as touchy as Canada’s dark history of residential schooling and the damage that it inflicted upon hundreds of thousands of indigenous students. They were forcibly taken from their families, enrolled in remote schools, and banned from expressing their language or culture in any way. More often than not these students were physically and sexually abused too. The Canadian residential schooling system was historically designed to extinguish indigenous culture and assimilate an entire race into a distinct vision of English-Canadian whiteness. It existed in Canada for much of the 19th and nearly the entirety of the 20th century. With the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2015, the history of residential schooling is only now beginning to be understood in terms of its human cost.

The purpose of The Raven and the Light is to introduce this history. And it does this with a story that is both fiction and not. Its invented details (characters and places) might not be real, but the horror of the experience is. To wit, it uses fictional horror to teach its players about the experience of a real-life terror.

///

It’s a defining experience of 21st century living to go down a digital rabbit hole and emerge differently on the other side. Case in point: about three years ago, Mark Basedow, a young, wiry first-time game maker from Ringwood, NJ, was in search of a setting for a horror game. “I wanted to do something with some meaning to it,” he says. After all, an explosion of independent game makers over the past decade has created more noise to cut through. “I was thinking of a cold area, and I typed into Google: ‘Canada’s dark past.’,” he said. What Basedow stumbled upon was Canada’s history of residential schools—something that the entire nation is still, in a way, stumbling through.

A lack of awareness about the history of residential schooling has allowed Basedow to break new ground with The Raven and the Light—quite possibly the only videogame to approach the subject of residential schooling, and one of only a few games that casts an indigenous person as its protagonist. It’s a simple fact that, for indigenous people, videogames have not been especially welcoming. The various histories of indigenous people—histories that contain some of the worst atrocities committed to a group of people ever—almost never make it on screen, and when they do it’s not in any meaningful way (think Custer’s Revenge (1982), which only worsens with each year in how offensive it is to Native Americans).

In western games like Red Dead Revolver (2004), and Gun (2005), killing “Indians” is rewarded, and indigenous characters are portrayed as a savage, primitive enemy. In countless other games, indigenous characters are only ever portrayed as warriors or North American quasi-necromancers. (It goes without saying, of course, that this is both a damaging and wildly inaccurate way of coming to know the histories and lives of indigenous peoples.) The Raven and the Light, in its small way, attempts to bring more attention to the true, and often unpleasant, aspects of indigenous history.

///

While The Raven and the Light has some elements that are expected in a horror game—at one point you have to escape a rapidly freezing room, while another has you dodge hungry wolves—these seem like secondary challenges. The Raven and the Light throws you into a virtual environment not necessarily expecting or demanding that you be challenged in any technical sense, but a social sense instead.

“I typed into Google: ‘Canada’s dark past.’”

History, while important, can be a hard sell; the nuances that tend to excite historians are not often dynamic or sexy enough for the general population. Museums can be distant and struggle to tell stories, books and articles might be considered lifeless, and architecture might not be interactive enough for some. Videogames offer new possibilities for the communication of history—especially difficult history—to those who might not otherwise learn about occurrences like residential schooling. It’s worked before, particularly with war—games often succeed in placing you in the shoes of a soldier, pilot, and so on. For archetypal figures, like soldiers, who are generally valorized, and who are not generally subject to the kinds of systemic prejudice that one sees when discussing indigenous peoples, very little is at stake: all glamor, but not often much substance. Soldiers are celebrated as honorable, the history is told through action set-pieces, but not much is typically said about people or culture.

With difficult histories, like the residential schools in The Raven and the Light, however, videogames offer “a very effective way of getting things about the culture to younger generations,” says Tehoniehtathe Delisle, a young indigenous individual from Quebec, who was enrolled in the Skins Workshop at Concordia University (a program designed to integrate indigenous individuals and culture into videogames by training young, indigenous game developers). “They really listen to it. If they’re playing videogames it’s like they’re actually active in the story—it’s like they’re the character, and they’re actually playing through this, and listening, and actually hearing these stories.”

In the past few years, indigenous communities have begun to explore the possibilities that videogames, as a medium, act as a channel through which to tell stories and relate their culture to the broader world. Earlier this year, a University of Sao Paolo anthropologist created Huni Kuin, a game that explored the history of the Huni Kuin, an Amazonian tribe who live in western Brazil and Peru. Other games have been used in more direct efforts of cultural preservation. In 2013, RezWorld was released (now branded as Talking Games). It’s an interactive game used to teach indigenous languages. In its first iteration it was designed to teach Cherokee, but has since been adapted to teach a vast array of indigenous languages.

According to Statistics Canada, indigenous populations are the fastest growing demographic in the country—meaning that there are a tremendous number of young indigenous individuals who are embracing digital media in a way that no generation before them was able to. “We’re in the digital age, and we need to create our own things,” says Owisokon Lahache, a staff member at the Skins workshop. “Videogames are becoming as important as any other mass media,” says Jason Edward Lewis, another staff member. “The more opportunities we make for ourselves as a people to tell our stories and to represent ourselves, the more powerful we’ll be as a people,” he adds.

for indigenous people, videogames have not been especially welcoming

Telling indigenous stories through digital media presents a new challenge for communities who have, in the past, had a greater degree of control over the way stories are told. “There are definitely people out there—native people—who don’t think that non-native people should be hearing native stories,” says Fragnito. “We treat very carefully—there are definitely stories that are not supposed to be told.” Young indigenous game makers, however, are more interested in telling their stories to a wide audience, rather than a selective one. “We say: this is going to be your story, and you can tell it as widely or as tightly as you want,” says Fragnito. “They want it to be as big as Assassin’s Creed III (2012)! The idea is that more videogames made by native people, with more native characters, to get a richer picture of who we are.”

///

Broadly speaking, things are getting better. Delisle also brings up Assassin’s Creed III, this time as an example of how indigenous cultures can be represented well. “They did a lot of research, and they had a lot of our language in the game,” says Delisle. “I think that got to a lot of the youth all over the place.” (The main character, Ratonhnhaké:ton—a half-English, half-Mohawk assassin—gets caught up in the American Revolution after his village is invaded. In addition to the positive and researched portrayal of Ratonhnhaké:ton, the game explored a less well-known perspective on a well-worn conflict through the use of indigenous characters and settings.) Programs like Skins aim to provide a platform for indigenous game makers to inject their characters, their voices, their experiences—in short, themselves—into videogames. The program, started in 2011, is growing, and is beginning to reach out to indigenous groups across Canada in hopes of improving representation and, perhaps more importantly, to help young indigenous individuals gain the skills needed to make inroads into the actual development of games.

It seems that indigenous game makers are realizing that videogames are a legitimate medium through which to communicate their cultures—and there are more resources and tools available that encourage and allow them to enter the game development industry. “Getting our culture out there is one of our biggest concerns right now,” says Delisle. “Legends are different throughout different nations. They change over time, and people tell them in different ways.” But all this may not be enough.

The Raven and the Light, like many smaller games, had a limited reach. It was downloaded about 2000 times, and enjoyed a handful of mixed reviews on YouTube. But then its existence seemed to be forgotten, it becoming yet another artefact of the internet. Its reach, though, does not diminish the effect of Basedow’s bigger point. Residential schools were, by just about every metric imaginable, quite horrible. But to many who didn’t live it, or whose families haven’t lived it, or who haven’t had the opportunity to learn about their history, residential schools can seem distant. By putting you within the walls, to confront a fictional story intertwined with historical fact, and by imploring you to learn more for yourself, it’s possible for the game to bring a dark history a little bit closer to the light.