Don’t let Quadrilateral Cowboy slip through your fingers

When Brendon Chung described Quadrilateral Cowboy to IGN in 2013, he framed it as a departure from his narrative-focused work in Thirty Flights of Loving (2012) and Gravity Bone (2008). “I wanted to go in a very different direction,” he said, “and let the player experiment in a sandbox and figure out their own solutions to problems.” This third game about the seedy underbelly of Nuevos Aires—the fictional city that many of Chung’s games are set in—is much longer and more complex than its predecessors, but shares many of the same ideas about how to string quotidian moments into a larger story.

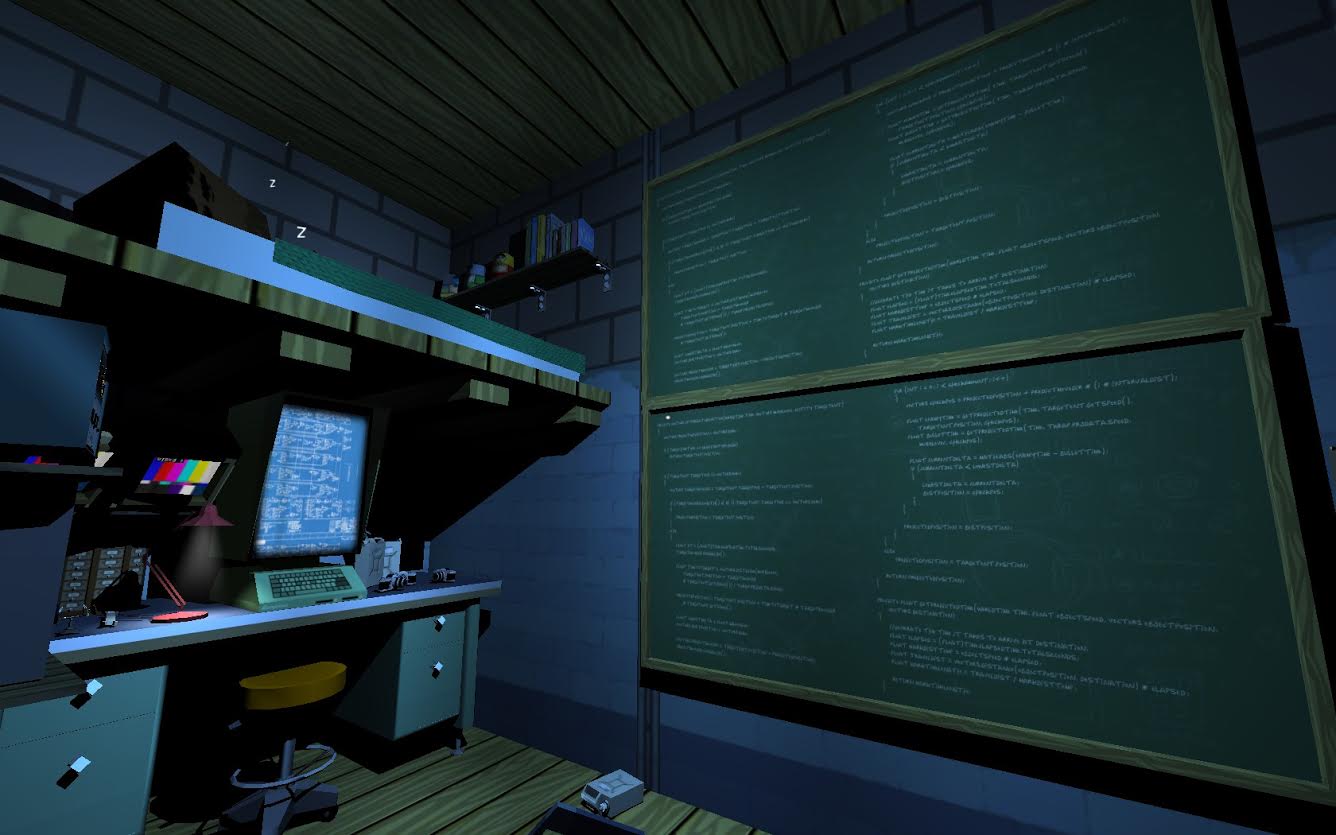

Like Portal (2007), Quadrilateral Cowboy oh-so-slowly eases you into a stack of tools, giving you a vocabulary with which to solve its puzzles. With a chunky laptop, a couple robots, and some clever programs, the main character Poncho hacks open doors in order to photograph secret documents or steal diplomatic pouches. In truth, though, you’re not on top of the cable car depicted on the screen, you’re tucked between shelves of whirring beige computer equipment, lit in fluorescent chiaroscuro. Your simulator sits in front of you, your eyes are crammed up against its headpiece as the analog machinery around you buzzes, and (judging by the misting fan) heats up the room.

Chung’s world-building is an exercise in metonymy

While you’re on VR heist-planning duty, your teammates Maisy and Lou are repairing machinery and doing chin-ups, respectively. Between heists, the cast of Quadrilateral Cowboy chills out. Less the hardened criminal degenerates of Neuromancer (1984), your crew of criminals are an everyday bunch of freelancers, taking weird gigs to get by once the regular repair and engineering work dries up. In “Carpool” levels, you pick each other up when it’s still dark out, and if you’re quick you can peek past Lou as she exits her home to see where she keeps her drawing tools and her crates of instant ramen. Through exploring the spaces you share with these characters, you come to some understanding of what their lives must be like, but also the realization that you’re never going to get to know everything—you won’t even meet the individual seen in Maisy’s bed (credited in the accompanying artbook only as “Sleepy”) as she slips out to hop on your hoverbike.

This is a technique that Chung has used and revisited before. In Thirty Flights of Loving, he zeroed in on a relationship shown in a handful of moments. It jump-cut from heist to wedding reception and back to establish that the action and the downtime rely on each other: both shootouts and quiet moments build and test the connections between its characters. And so, like its predecessor, Quadrilateral Cowboy isn’t focused on one at the expense of the other, despite its longer form and more complex action. Gravity Bone included, these games are about small stories, and presenting enough of the right fragments to convey a close relationship between friends, or a betrayal, or regret.

Similarly, everything about the locations of Nuevos Aires provokes the feeling that it’s bigger than what you can see of it. Its blockades, time restraints, and unseen actors provoke questions: Who owns the villa you’re infiltrating? Who are the sleeping bodies in the Repulse Bay Clinic, and why are they in an apparently robot-run hospital in space? Is the brain in a vat any good at trading stocks? Chung’s world-building is an exercise in metonymy—you are encouraged to wonder at the gap between the simulated space and the real version of it, left completely untouched. Chung doesn’t use overt environmental storytelling in the form of weirdly explicit graffiti, instead he packs every inch of Quadrilateral Cowboy with books, food products, notes, and personal effects. The result is a world that feels fantastical, but relatable, with idiosyncratic characters who are defined by their own preferences and actions rather than only through their interactions with you.

While there are a number of signature Chung moves throughout Quadrilateral Cowboy there are also subversions of them that show a maturity beyond his previous efforts. With Gravity Bone, for example, Chung seemed interested in critiquing typical game form: its mission structure and scoring suggest it’s going to be a long and exciting game about espionage action, but its ending puts the lie to that. When its master spy protagonist is suddenly shot and killed, it’s anti-climactic and disempowering. The expectation that the extraordinary main character will succeed against all odds is betrayed, and as he dies, his life flashes before his eyes. It’s a short experience that uses its implication of a larger game to also imply a larger life, of which you saw only a slice.

a game about reflecting on life

Now, some years later, Chung has moved on. No longer is he critiquing traditional game structures, he’s finding narrative solutions to them. This is seen in Quadrilateral Cowboy’s virtual heist preparation, which avoids obvious satire to instead invent a reason for repetition and mastery to exist within its narrative. Take the very last mission, which took me about 15 minutes to beat on my first run through. I set off a couple of unnecessary alarms at first, but eventually I got in and out. I played through it again and again, glancing at the stopwatch that stares at you from the bottom of the screen, eventually pulling off the heist in just under 2:30. Through this repetition, Poncho learns how to tackle a problem in her sleep, in under a minute. I’m blinking my mechanical eyes to deactivate the laser mesh in front of me and downloading brains at a breakneck pace, but only because I’ve screwed up many times before. The code you input is stored in your deck for the next run through, so you can scroll back up through what you’ve written, or connect every line to a blink command, and run through levels without using your deck at all.

This is how, through its heists, Quadrilateral Cowboy becomes a fantasy about mastery. Its three main characters are able to scrape by not because of their augmentations or inherent ability, but because they are prepared and meticulous. Pursuing this fantasy is also why its computer systems are simplified, made accessible. In that sense, the game’s vision of hacking isn’t any more accurate than Hollywood’s—where a couple keystrokes gets you into the Pentagon—but even when Chung abstracts the act of hacking, your interactions with the world are grounded in the step-by-step logic of programming. A hacking game where you can mistype a string of commands and spend a minute hunting for your typo is a rarity. But when it does show up, it means that, through repetition, you can improve your own play as you come to fully understand the scripting and the layout of the level you’re rushing through. Unlike Gravity Bone, it’s not about the thrill of the job gone wrong, it’s about the thrill of getting it right. Even in that last level, you don’t quite have to use all the tools at your disposal—the game spends so much time teaching you how to use your cute robots and your scripts that just as I started to feel like an unstoppable infiltrator, it was over.

With Quadrilateral Cowboy, Chung eschews the filmic jump-cuts he experimented with in Thirty Flights of Loving. Still, the fragmented plot produces a similar result: as it happens, it already feels like a collection of memories. The jobs and vignettes are this gang’s “Greatest Hits” strung together in a way that gives you an image of what they did as work for 15 years, but also their proudest and fondest moments. In some sense, it’s a game about reflecting on life, as Chung’s narratives often are. As such, Poncho appears to escape a violent end to go on and live a long life, but it’s clear the Good Old Days don’t last—days of sharing noodles and stealing your boat back from the impound lot give way. Like the hacking missions, you can replay these nostalgic moments as many times as you want, but you’ll acquire no increase in power over them. Throughout the game, you learn to manipulate environments and the analog systems that drive them, but relationships are out of your reach, withering beyond your control.

In the last minutes of the game, as in the opening, you approach a train on your hoverbike, Clair de Lune playing once again on your portable record player. Now the train’s not the target, but Poncho’s—and only Poncho’s—living space, covered in books, old gear, and scrapbook photographs of the team. Back in the hideout, Maisy reads books with titles like Violent Passions, but in the train car, under a dusty box, there are books with titles like Legal & Financial Guide to Family Caregivers. At the end of the game, when you’re sorting through this gallery of tools and photos, you’re not a safe-cracking net-hacking superhuman any more, you’re just a regular person that time caught up with.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.