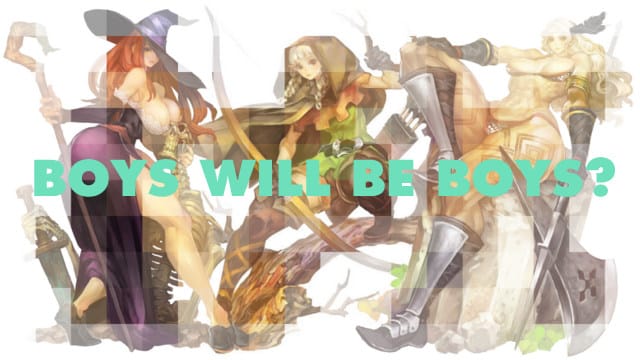

Dragon’s Crown is maximally silly and adolescently sexual

When I was 9, my family moved, and I had to make new friends. I was fortunate to quickly fall in with a group of boys with whom I shared two defining life-goals: to someday be a successful comicbook artist, and to someday see a naked woman. Eventually, these twain yearnings fused into a perfect expenditure of our free time. We decided to sell markered-in drawings of comicbook characters to friends and family until we raised $25, a sum we all agreed upon as sufficient to entice a sensible adult to buy four pre-teens a dirty magazine. We studiously set to work producing the artwork, which he had big dreams to sell at $.50 a pop, and of which we then sold exactly zero prints for a gross of zero dollars. I think we stole a Playboy later that week.

Across the world, I imagine that a young George Kamitani had an identical adolescent experience, only without the closure of the pilfered magazine. He seems to still be spinning his wheels, gaining steam, building toward that purchase. His work as the head artist and designer at Vanillaware has been marked by some of the most lush fantasy artwork ever seen in the medium; the games are concept drawings come to miraculous life. And as the studio has shuffled through various RPG sub-genres, they’ve also become known for indulging Kamitani’s libidinousness, produced with the same sense of biological compulsion found in the work of R. Crumb or the Japanese pop artist Mr.

Kamitani’s latest game, Dragon’s Crown, represents an apex of both trends, but here he’s moved from gonzo, manga-inflected weirdness toward something decidedly more Western–and classical. The hulking dragons and knights here are all Arthurian fantasy, or at least inspired by the things inspired by Arthurian fantasy. Four players–it’s almost mandatory that they be splayed across the same couch–pick among archetypes to send through a nonet of ornate levels, firing off magic missiles and axes at wyverns, vampires, and snarling dog-bears. For some, one must assume, these images rekindle memories of a childhood spent absorbing Boris Vallejo paintings and D&D rulebooks; for others, one must assume, they are the images of a childhood still being lived.

These images rekindle memories of a childhood spent absorbing Boris Vallejo paintings and D&D rulebooks.

There is probably a third class of person–those who are not either children first discovering high fantasy, or high adults indulging their fantasies–and for this third class of person, the game must look preposterous indeed. Because for all its immaculate, painterly beauty, the characters interact like immaculate, painterly clipart. When an immense three-headed dragon crashes through the floor it does so as a sequence of vaguely interconnected pieces of construction paper, like a monster from South Park. It is juvenilia writ in tones of somber portentousness. We’re to leer with delight as the improbably proportioned Sorceress bends over, on the pause screen, and rests a magical staff in the crevice between her ass cheeks.

This is a) embarrassing, and b) an illustration of the game’s central tension: between the bulbousness of its character design and the flatness of its presentation; between the elegance of its overarching structure and the trainwreck of its menus; and, lastly, between the seriousness of its tone and the stupidness of its story. It teems with this tension, ready to burst. A nonsensical plot and lackluster translation are practically Vanillaware calling cards, but here lore oozes out of the screen like pus from an over-ripe zit. Full backstories are conveyed as parenthetical asides; a complex palace intrigue is introduced, then discarded; the titular crown is a defining MacGuffin that is nonetheless preceded by quests for orbs, fairies, and nine goddamn talismans.

But here lore oozes out of the screen, like pus from an over-ripe zit.

Perhaps this inner confusion is expressed nowhere as elegantly as the loving way it tells you to progress. A sprightly British narrator reads, storybook-style, every plot point and line of dialogue in the game. In lilting, avuncular tones, he is saddled with both retaining conviction throughout the many plot contrivances and creating characters out of this obscene parade of flesh. That an actor would even attempt this is commendable; that over the course of twenty hours or so we hear him largely succeed at it is a performance akin to Michael Jordan’s flu game. In the grand spectrum of videogame narrators, the effect is closer to Stephen Fry’s docile, ornamental turn in Little Big Planet than Logan Cunningham’s mechanical implementation in Bastion. The goal is not to dazzle with the narrators’ omniscience but to merely envelop the player in warm, velvety ambiance.

He has a propensity for launching into the same canned narration repeatedly, its initial silliness growing only more sublime with time. “The resurrected magician has returned to the old tower in town,” he chirps, and as each player enters and then exits the shop to unload their loot, the narrator chirps anew that, yes, the resurrected magician has returned to the old tower in town. While the player frantically attempts to figure out the menu system, the narrator will serenely expound on the magical properties of orbs. This blend of ineptitude and polish mirrors the game’s slow, confident maturation, from a mawkish RPG into a long-playing score attack, and somehow crystallizes the whole experience, not so much as parody but certainly as comic in nature.

Which is, ultimately, why the game requires in-person collaboration: it’s an embarrassing game in many ways, but it is also, at least, very funny. That distance is helpful. Now in his 40s, Kamitani has created the most personal game of his career, one that is as awkwardly oversized as adolescence itself. He has been rightly criticised for the problematic indulgences of his art design, but it’s exciting to see someone’s messy, gnarled id onscreen. I’d rather see more of that than less, but I’d also rather see those expressions be more representative of the actual array of human desires than exclusively those of a nine-year-old boy.