A certified pioneer of game art, Eddo Stern is an LA-based artist who is also the Founding Director of the UCLA Game Lab. Born in Tel Aviv and now based in California, Eddo has been making games and interactive artworks for decades—his fantastic practice centering on the deep tensions of life and the human condition.

We’re grateful to have spoken with Eddo about the interplay between form and content, how his pedagogical and creative practices feed into each other, and his ongoing, multipronged project, Vietnam Romance.

How has the UCLA Game Lab shaped the way you think about games and interactive practice?

My background is in contemporary media art. My earlier work was always built on the criticality of games as popular culture and investigating them. Usually, originally not in game form, but in film form, machinima filmmaking, sculpture performance, and eventually intervention and modifying games and a gradual transition into making games. Once I started working at UCLA, the biggest change was that this was a Media Arts and Design program where I teach in the Lab, even though it's situated to serve all the arts at UCLA—film, theater, design, architecture, fine art, music, and other departments. This shift from thinking conceptually as the primary way of doing work is how I work personally. Working in the Lab with so many visually-oriented students helped me appreciate the importance of design.

When you talk about game design, it's usually conceptual game design, rules. Design is a bigger practice, and for being an artist who's always been skeptical of design, being so utilitarian and enjoying the freedom of art not to be instrumentalized all the time. However, it does become instrumentalized, but fighting against that within an art context has always been my practice. Working with more designers who think differently about everything changed my practice and activated a 10-year journey of learning how to be a designer. Then I became comfortable calling myself an artist and a game designer.

I look at the Lab as being built on tensions, which again is what motivates me often in my work—things that push against each other. Something awful and tragic and then a comical counterpoint and how that makes us feel, or looking at the world through the internet, for instance, and experiencing everything side by side.

The Lab now can encourage so many diverse points of view and approaches to games. The joy for me is not cutting any of them off and saying, "This Lab only does serious games," or, "This Lab only makes beautiful games," or, "This Lab only makes playable mechanically sound games or commercially games that are commercial or games that are even non-problematic." I don't want to cut off anything.

Working with such a more diverse group of students has taken away this idea of here's Art, over there’s design and over there’s entertainment. It’s allowed everything to be appreciated—and to start looking at them critically across all directions.

New media art is always about, "What's the newest technology?” To question that with analog games, for instance, games that have nothing to do with that, and the objectness of the materiality of game pieces and then suddenly seeing like, "Wow, physical games have just been so almost blind to that whole aspect of how they're made." They're produced in such an overly-mechanized and routinized way.

How has the UCLA Game Lab shaped the way you think about games and interactive practice?

My background is in contemporary media art. My earlier work was always built on the criticality of games as popular culture and investigating them. Usually, originally not in game form, but in film form, machinima filmmaking, sculpture performance, and eventually intervention and modifying games and a gradual transition into making games. Once I started working at UCLA, the biggest change was that this was a Media Arts and Design program where I teach in the Lab, even though it’s situated to serve all the arts at UCLA—film, theater, design, architecture, fine art, music, and other departments. This shift from thinking conceptually as the primary way of doing work is how I work personally. Working in the Lab with so many visually-oriented students helped me appreciate the importance of design.

When you talk about game design, it’s usually conceptual game design, rules. Design is a bigger practice, and for being an artist who’s always been skeptical of design, being so utilitarian and enjoying the freedom of art not to be instrumentalized all the time. However, it does become instrumentalized, but fighting against that within an art context has always been my practice. Working with more designers who think differently about everything changed my practice and activated a 10-year journey of learning how to be a designer. Then I became comfortable calling myself an artist and a game designer.

I look at the Lab as being built on tensions, which again is what motivates me often in my work—things that push against each other. Something awful and tragic and then a comical counterpoint and how that makes us feel, or looking at the world through the internet, for instance, and experiencing everything side by side.

The Lab now can encourage so many diverse points of view and approaches to games. The joy for me is not cutting any of them off and saying, “This Lab only does serious games,” or, “This Lab only makes beautiful games,” or, “This Lab only makes playable mechanically sound games or commercially games that are commercial or games that are even non-problematic.” I don’t want to cut off anything.

Working with such a more diverse group of students has taken away this idea of here’s Art, over there’s design and over there’s entertainment. It’s allowed everything to be appreciated—and to start looking at them critically across all directions.

New media art is always about, “What’s the newest technology?” To question that with analog games, for instance, games that have nothing to do with that, and the objectness of the materiality of game pieces and then suddenly seeing like, “Wow, physical games have just been so almost blind to that whole aspect of how they’re made.” They’re produced in such an overly-mechanized and routinized way.

You talked about how you’re drawn to this idea of tension and contrast. Is that a long-term concern in your practice? If not, what are your concerns at the moment? At this moment right now as an artist?

It’s always been one of the driving energies behind my work and how I look at the world. Part of that is growing up in Israel and looking at that culture already but then moving to the US, looking at cultures and cross-cultural representation. Anytime you move between two cultures, you start to see things differently. Almost all my projects have this investigation of some kind of complexity, and looking at complicitness in everything is concerning to me.

The burden of responsibility and personal-political agency versus community versus destiny versus tradition. Life is full of these questions and they don’t go away and they get more rich and nuanced and shift. It’s almost always inherent in every project. Humor, dark themes, and horror, is where horror can happen when it touches on real experiences or references. Then horror and humor together have always been something that I find bits of in my work. Video games or computer games, especially, are almost the medium, for me, that embodies this tension.

I am drawn to this notion of the perversity of games—especially computer games where there’s a gradual replacement of human interactions, they’re mechanized and computerized. It touches on many dystopian ideas, and gamification is an incredible example seen very positively by the media. We see all those books and then the dark side of it of “Let’s manipulate the lizard brain to get people to do what we want through addiction, through obsession, through competitiveness, through insecurity.” Games become almost a systemic mechanization of exploitation of certain human behavior. On the other hand, I revel in that perversity too. Hardcore gaming interests me like obsessive online gaming and playing for years and being completely immersed in character or hyper-competitive games.

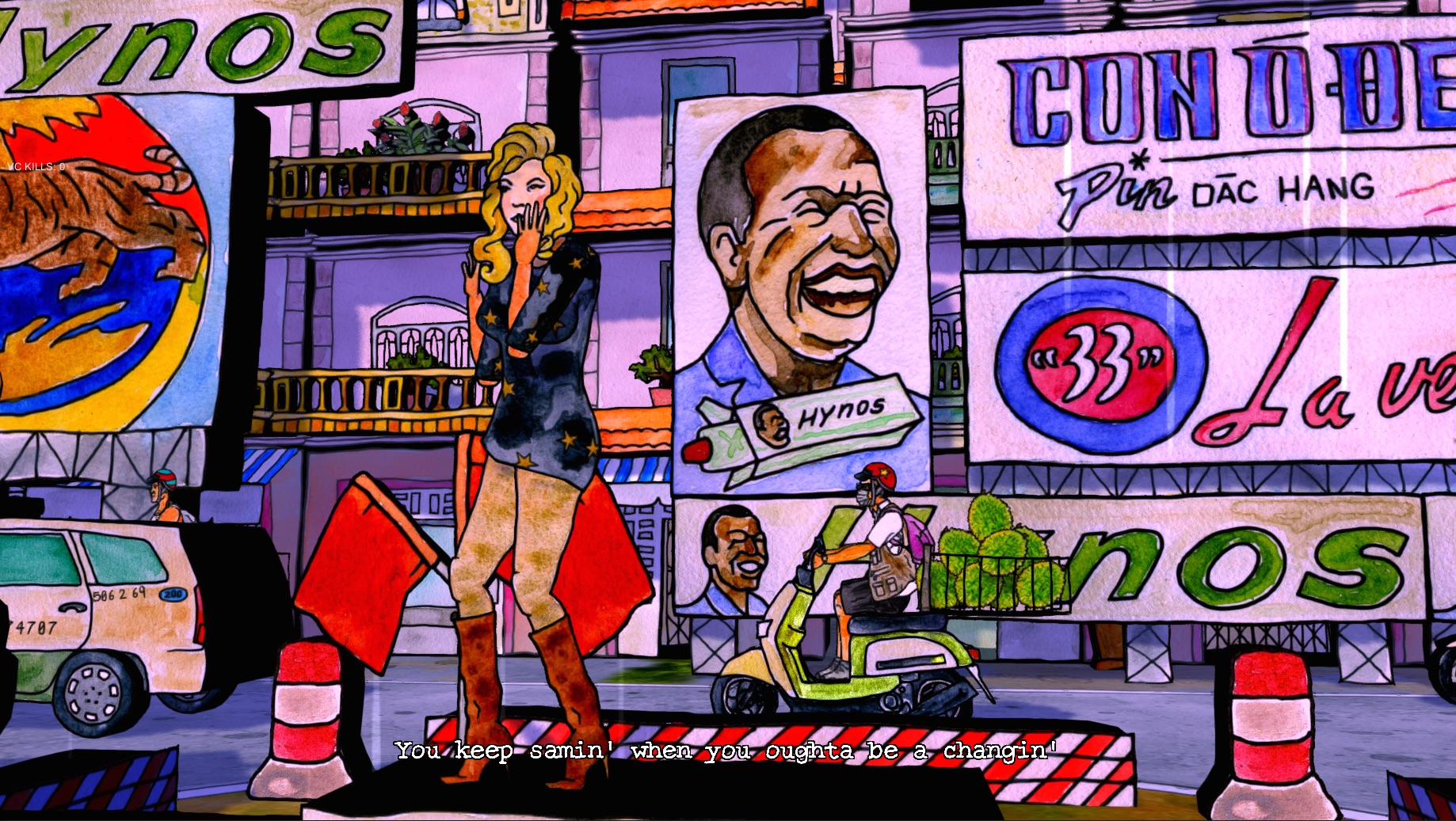

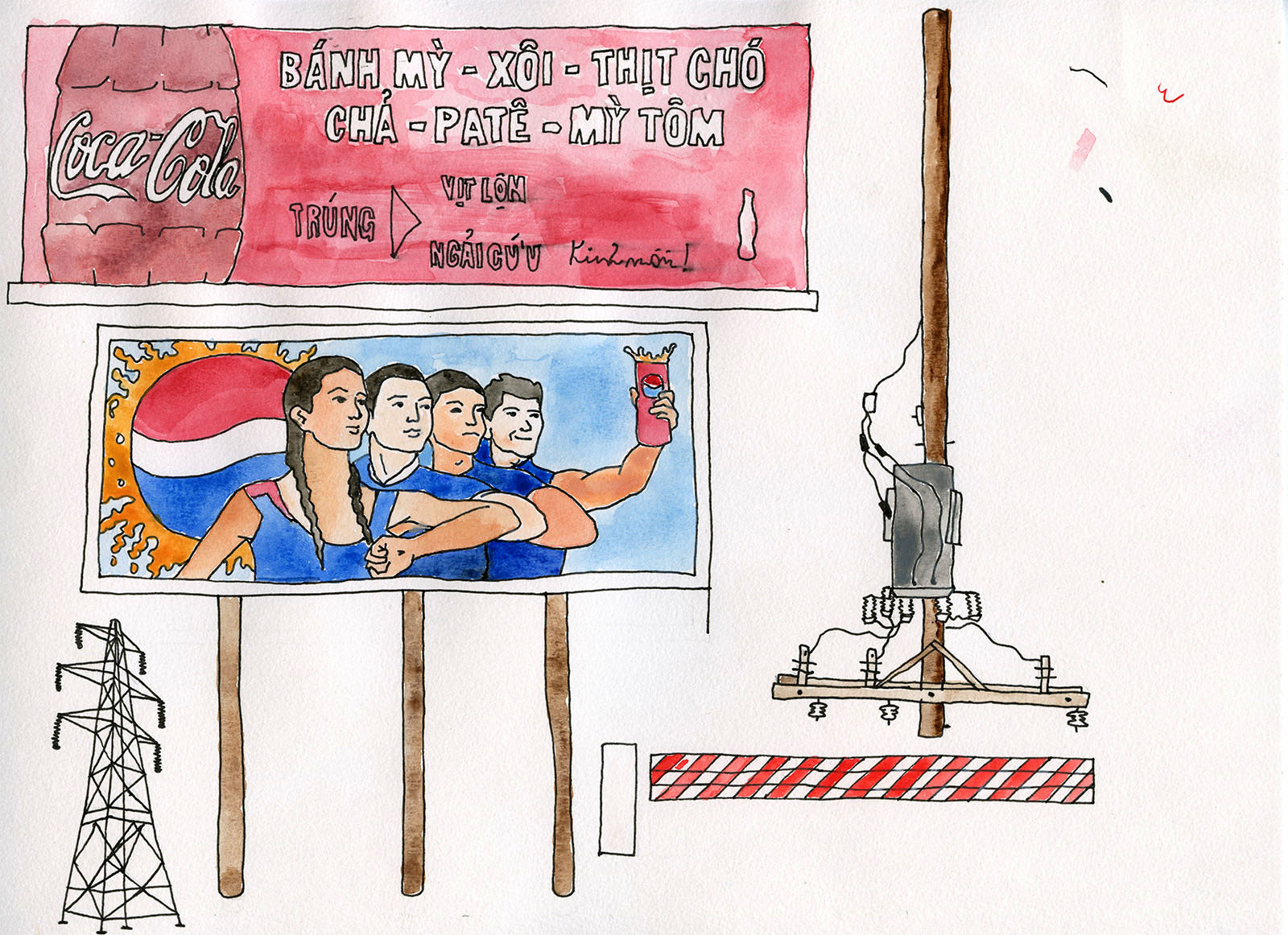

Tell us about your ongoing project, Vietnam Romance.

It’s a big project about history being replaced and rewritten by remediation. Because it’s been a project that I’ve been working on for years, it has many other layered ideas. It becomes about travel and about neocolonialism and about the consumption of eBay shopping for experience. A quest for experience is what it’s about philosophically. People are nostalgic for the ’60s. They’re nostalgic also for that turmoil, and the Vietnam war is a vehicle for nostalgia that is disturbing. How does that map onto other realities of what is happening now?

I’ve gone to Vietnam a few times to work, do research and document and build worlds. At the War Atrocities Museum, and they have a gift shop, and they have a whole library of American books written by soldiers all shrink-wrapped. They’re all fake books. They’ve been photocopied, but they’re all for sale. Then there are all these bins all around in the gift shop, government-owned, of medals, war medals from American GIs, and patches. They look worn and they’re all fakes and they’re all handmade fakes that have been burnished. Then the eBay vendors that then manufacture these things and sell them to Americans on the internet. Vietnam Romance is an ambitious project, and it takes time because it’s a small team and just trying to finish it.

More recently, I’m becoming very critical more and more and not cynical, but discontent with social media; the corporate umbrella around everything. The agility now of certain corporations to respond so quickly to subculture. Places like Instagram are thinking like game designers like, “Let’s manipulate. Let’s create this space for people to perform and feel that they have agency within.

That disturbs me. I’m thinking a lot about counterculture and how can it exist at this moment where there’s this compulsion, especially younger people, to have to perform in these public online corporate spaces to be relevant in the society. What are the alternatives; how are they possible? I’ve always been interested in community building and alternative space building. How do you reconcile the digital and this corporate infrastructure that so much of our technology is based on and still be relevant?

The turn to analog is definitely an interesting thing and humanizing and working on more humanistic projects is very important to me. One of the advantages of digital media and reproduction is scale and impact. What impact does scale have on how many people are using it, or can you create things that actually can do both? They’re distributed ethically, and I know this is what the corporations are trying to do with these things, but there’s got to be other values that can achieve this.

Vietnam Romance has taken on many different mediums and forms. What is the effect of implementing a mix of digital and analog mediums for your projects?

Part of it is non-deliberate, a circumstance of coming from art making where some certain processes and structures are very different from filmmaking or novel writing where you say, “Well, I’m working on this thing and I don’t want to show you an excerpt,” and when it’s done is when it’s done. It doesn’t have much of a life between. With novels, maybe people can read a little bit, but certain media. With art, there’s always been a lot of possibility to improvise, to respond.

As a medium, contemporary art trains you to be very responsive and say, “Here’s an opportunity, we’re in Minneapolis and there’s a Vietnamese restaurant that I have a connection to and we’re able to do something together and I’m going to do that,” or do a live theater show in New York at Babycastles. It’s like it was the right time to do it. The game isn’t finished in a sense, but I believe that all these experiences are meaningful, that doesn’t have to be this kind of, “Here is the monolithic full game,” because who knows, you make that whole game and someone’s going to be excited about some very specific thing in them.

You read a whole book and you remember one little exchange. With Vietnam Romance, that’s been how I approach it. The project becomes a muse and the mixing of the media reflects my projects containing contradictions and tensions. Scale, people are like, “Well, why do you need to make a video game gigantic?” We built a giant big analog CRT that was 20-feet tall and had a rear projection, and you’re this little person hooked up to it with it. Museum guests play it and that completely changes. It makes you think about a system and a player very different from you with all the agency.

There is no logic to it other than experimentation and pushing things together from different media to see what they can do. I’m a very undisciplined artist in both terms of that word—so I don’t have discipline and I lack discipline as well. On the positive side, I found it to be a great partner for experimentation which is a term that gets thrown around a lot and people value it I think. Still, often they don’t value it because what people want is accomplishment, completion, something.

I believe in experimentation as something valuable. Still, it must produce something, that it’s not apologetically an experiment. It’s emphatically an experiment that is really important to me in my work and in the lab and keeps me going. Almost always try something new when you can. The mashup of media is also working to open up new space for what can be done.

It’s been rewarding to see these experiments or this lack of discipline produce resonance in other artist’s work—whole approaches of looking at things because my training and other people’s was on discipline. We’re allowed to do things that you couldn’t do in a company, or if you had to make a serious game about something, or you had to make a commercially viable object, or you had to show something at a fine art museum, so it had to be palatable for a certain.

By moving between film, and theater, and performance art, and sculpture, and all that blending—it’s not just chaos, it’s each one provides an opportunity for collaboration.

How does collaboration factor into your work?

I have a project called Games With Friends in which I work with other artist friends who really aren’t game folks and just say things like, “Let’s try to make a game together with equal weight to different practices and see what that produces.”

Within that project, I like a project called Goldenstern—It’s like a family tree Pachinko pinball game. All the illustrations for it are made by my friend, John Haddock who’s an artist and illustrator. We have a similar perspective on the horrors of pop culture and personal life folding into fantasy life. He’s a really close friend of mine and it’s a long story.

He has a very complicated family history and he was telling me about over dinner and while he was doing that, I was taking notes just because there were so many people and it was so complicated. I created this diagram of his and his wife and family with all the characters and it was like this artifact. That sat there. Another idea is like I was always interested in my family’s noses. We’re from Israel, Jewish family, a lot of hooked noses in the family. My wife, her nose is the opposite, and her family have these very curvy noses.

I wanted to make some game where you scan your nose and then just a skiing game on people’s noses. Also, I thought it would have to be about Judaism and big noses. Then we had a kid.

All these ideas combined into one project—John Haddock’s family tree, the noses of my family, worrying about children and their future, some almost comical but disturbing references to money and inheritance funneling in. This game funnels money to this child, our child at the end, through these different families. I often thought about that project as games-as-portraiture.

For your projects, how do you think about form and concept in tandem?

It’s a fundamental question. It’s where the magic can happen. People often ask, “How’d you come up with that style?” I respond with, “It comes from an inability to draw a different way or not really being a good 3D model.” There are many ideas bouncing around all the time. It’s what I do all day. They’re both conceptual ideas and sometimes structures or systems, what you would call maybe a medium but they’re always being investigated and rethought.

I’ve always been sensitive to what I call the Grid Theory—there’s basically one axis: new media emerge and become available, games, VR, AR, AI, machine learnings, outer space, bioengineering art, whatever, cloning, camera surveillance, drones.

The other axis consists of tried and true concepts: a self-portrait, an investigation of gender inequality, a historical revisitation of place, minimalism, abstraction, expressionism. Then there becomes these triangulations on the grid like, “Oh, let’s take drones and self-portraiture. What do we end up with? Okay, let’s make a drone that looks like my face and I’ll fly it around.” “There is my self-portrait as a drone.”

That would be a project that would get attention in a new media concept. It’s highly problematic as an artist to think that way where you’re adding X to Y to create Z. It takes you out of the equation; you’re just filling these blocks. Being aware of this problematic binary dual way, I just have them all floating and the way they connect almost has to be serendipitous. For me, it’s not a deliberate choice exactly. I’m mostly interested in conceptual projects, but also I care about media and experimentation and formal experimentation.

The medium is the message is certainly a provocative and strong statement that any media artists would take dear to their heart. That’s what it is. Again, as more people make games specifically who don’t come from art, but from other media, they have very different approaches. “How do you preserve this multidisciplinary medium? In games, it’s like, “Programmer, Artist, ‘Game Designer, Producer, Conceptual Designer.'” How does that hierarchy play out? Does it need to be a hierarchy? It’s also really important to constantly shuffle that. Again, that speaks back to your previous question of concept and format. That’s shuffled all the time. You’re never subordinating one of these aspects of a project to the other.

You’re not saying, “For me, it’s all visual,” or, “It’s only concept,” or, “It’s only the cool game mechanics.” Basically, everything is a mess [laughs].

Credits

Photography courtesy of Eddo Stern.