Food is a precarious material to work with. It can crack open, ooze, spoil, decompose. A harsh contrast to technology, which is hard, cold, almost unforgivably unyielding, and a toxic scourge on the earth. Just ask food technologist Emilie Baltz.

In one of Baltz’s earlier food design projects, she worked with gelatin, creating a giant gelatin speaker by embedding a sensor into a gelatin mold of a hi-fi speaker. The hope was that when someone touched the speaker, it would trigger a sound and, because of the sound waves, wiggle. Only Baltz didn’t take into consideration gelatin’s melting point (and the fact that people really just want to stick their finger inside of a gooey mold). So over the course of a few hours at room temperature with the added human heat of people’s hands, “the whole thing melted.” Baltz now uses agar, another jelly-like substance used in cooking as a vegetarian substitute since it is obtained from red algae, which is more temperature stable. “Gelatin doesn’t really like to be touched,” she said.

“Talk about choosing two things that never work, food and technology,” Baltz said. “They’re like oops, the broccoli didn’t ship today and this sensor is actually pressure-sensitive, shit. Nothing ever works as planned.”

Baltz doesn’t consider herself a chef or a game designer, but food is her medium and creating interactive experiences is her endgame. She first studied screenwriting and contemporary dance, so she comes from an education in storytelling, and then received her masters in industrial design six years after graduating college.

She stumbled upon food as a material design while she was working as a waitress, and in 2005, this was largely uncharted territory, using ingredients as a medium for interaction. During the rise of molecular gastronomy in 2004, much was happening in the world of food. Chef Wylie Dufresne’s wd~50 was perhaps the most prominent example of molecular gastronomy in America, which operated on the Lower East Side from 2003 through 2014. “The kitchen, just a few blocks from the restaurant, has become a lab for subjecting ingredients to extreme conditions,” the New York Times wrote just ahead of the restaurant’s opening in 2003. Duresne and his team used non-traditional cooking techniques fused with science such as “slivers of calamata olives are withering to a crisp; […] pineapples festooned with peppercorns and vanilla beans are completing a three-day braise; in the freezer, tubs of lovage await an undetermined fate.”

Other New York chefs followed suit and around the world they continued to open up wild restaurants that really explored and challenged how we think about food. Think kitchens turned R&D labs.

“There is a real need for experiences that force us into these spaces that are physical, that are real, that aren’t mediated by huge amounts of tech”

Other New York chefs followed suit and around the world they continued to open up wild restaurants that really explored and challenged how we think about food. Think kitchens turned R&D labs.

“[Food]could be an idea. It could cause an intellectual conversation,” Baltz said. “It could be science; it could be romance; it could be so many things because of the way the material was treated.”

She started to think about how food could be applied to human design principles. “Chefs here were using it still as an ingredient in a dish,” she said, but she wanted to explore how it could be used to build social relationships and relationships to our environment. “It fed my curiosity to no end because there was no research at that point.”

Food is our only multisensory material—we see it, we hear it, we smell it, we taste it, we feel it. It lends itself to intimacy, shared experiences, emotional and cultural nostalgia. Tech, these days, is more often attributed to an unfeeling, alienating phenomenon. A study published in 2018 in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, for instance, found a causal relationship between Facebook, Snapchat, and Instagram usage and increased depression and loneliness. “The screen has done such a disservice to all of us,” Baltz said, adding that when she teaches, she sees that reality in her students, and how technology has bound their creativity.

“There is a real need for experiences that force us into these spaces that are physical, that are real, that aren’t mediated by huge amounts of tech,” she said. “What food does when you introduce it is it really grounds you in your body and you have to feel things in public with other people.”

Baltz doesn’t usually pick a food or ingredient first and then go from there. Her projects usually start by asking how she wants to make people feel. (Though she did say she does want to do some work with bioluminescence, the emission of light from a living organism. Like a firefly.) Food might be the play object, the controller, but how that interaction will make you feel is what Baltz is after.

“If you think about walking down the street and drinking versus sitting in a cafe and slowly sipping your cup of coffee, they may be the same chemical composition, but you’re going to experience and feel that coffee in different ways because of the interaction and choreography around it,” she said. “That’s usually how I start, and then find food and flavors that complement that.”

Baltz is tapping into a larger cultural vein. Eddo Stern, a Professor of Design Media Arts within UCLA’s Game Lab, said there is a cultural moment unfolding as people are growing hungrier for experiences that aren’t purely digital. More people are gravitating toward board games, for example, and in general, toward games that are more personal. He cites alternative controllers as an example of catering to that desire for a more humanistic gaming experience.

Stern himself has developed a number of games with alternative controllers and twists on more mainstream virtual spaces—he’s designed a “Triple Mouse”, hard plastic 3D skins of cult leader David Koresh, sensory deprivation head gear, and, like Baltz, gameplay that incorporates food.

“In my own work they were serving a particular purpose, usually to bring focus to the body while playing,” Stern said. “So much about computer games strives for deep immersion and disembodiment,” he said, citing virtual reality as an example, but his projects focus on bringing that awareness back to your relationship with reality, they “make you aware of your body, of who you are, what you’re doing.”

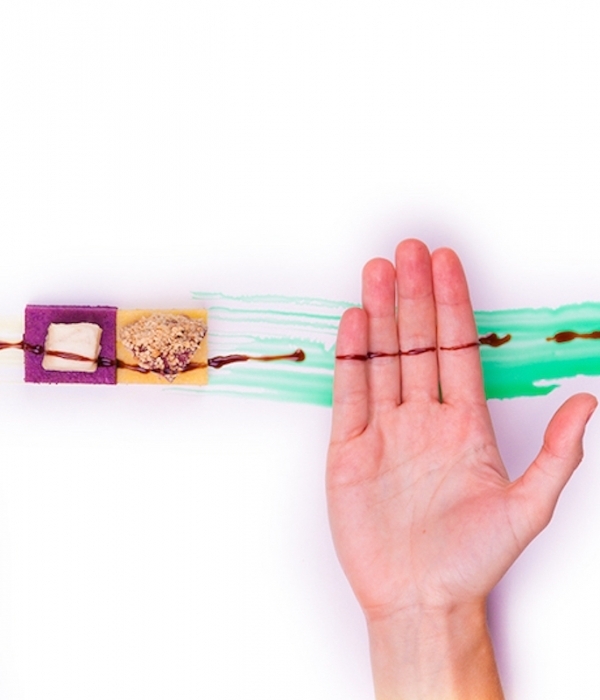

Baltz also wants to create experiences that deepen people’s understanding of their body, their motivations, their emotions. Eat Tech Kitchen, her recent project, asks people to cook dinner using a basic chatbot embedded in Google Home. “The idea is that you’re cooking recipes that are coming from the future of humanity and the irony of it all is that the recipes are really, really stupid and they look at humanity through this lens of contemporary culture.” People are asked to do things like use their phone as a plate or lick a Twinkie as many times as they liked a photo on Instagram.

“It mixes all the language of digital behavior and digital culture and in exchange asks people to make these little snacks together,” Baltz said. Food is used as a medium for play here, “but it also serves as a familiar way of being able to engage people in critical dialogues with themselves using a recipe.”

It’s this nudge to get people to look at themselves, to laugh at themselves and with each other, and to critique themselves through a gameplay that is familiar to most of us—following a recipe. And it’s hopefully a nudge further from this alienation of tech and closer to looking up and connecting with others, and with yourself.

Credits

Photography by David McDowell