The English melancholia of Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture

This article is part of our lead-up to Kill Screen Festival where Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture artist Alex Grahame will be speaking.

///

“These are the dark November days when the English hang themselves!” – Voltaire

///

The English are known for a number of bred-in-the-bone traits but chief among them is a certain melancholia. There is nothing uniquely English about being a bit sad but history has latched it to us as part of our national character. Perhaps it is our artists who are to blame for this. John Dowland, the Elizabethan bard, is remembered for his motto: “Semper Dowland, semper dolens” (“always Dowland, always miserable”). Centuries later, Blur and Gorillaz frontman Damon Albarn—who calls himself “an English melancholic”—would echo Dowland’s sentiment, especially with song titles like “On Melancholy Hill.” As Jules Evans notes, Albarn is only one of many modern English musicians to hit upon that pensive chord, along with Amy Winehouse, Morrissey, and Nick Drake. And surely it’s no coincidence that goth rock started with morose English bands like Bauhaus, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and The Cure.

overlooking the villages below as one would a burial ground

Then there’s the so-called “graveyard poets” of the 18th century: Englishmen who wrote gloomily about death, coffins, bones, and our eternal rot in the ground. Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751), among others, did the job of kneading this national melancholia into an association with the English countryside. “To Continental observers hypochondria was notoriously The English Malady before 1733 when Dr. George Cheyne published his book of that title,” writes George Sherburne and Donald F. Bond in The Literary History of England: Vol 3 (1959), adding that it was during the 18th century that “the English acquired an international reputation for suicide.” The fashionable artistic image of the time became one of an Englishman sat atop a knoll, skull held in one hand, the other penning his wizened thoughts on mortality while overlooking the villages below as one would a burial ground.

That poetic image dominates the tone of last year’s Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture. Made by Brighton-based studio The Chinese Room, it has players explore a small English village in the wake of an apocalyptic event that has caused all the residents to suddenly vanish. Players discover what happened to these people by chasing the traces of human life that remain in the idyllic environment. Manifesting as orbs and particles of light, these theatrical remnants reveal the various tales of loss and grief that the villagers were in the throes of when they were stricken. But these fading presences are fragmented and so a greater well for players to draw from in their investigation are the physical details left of each character’s struggles inside houses, and across the many streets and fields. It’s there that players can see the work of Alex Grahame, one of only a handful of artists who worked on Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, and who will be speaking about how she designed loneliness in this role at Kill Screen Festival on June 4th.

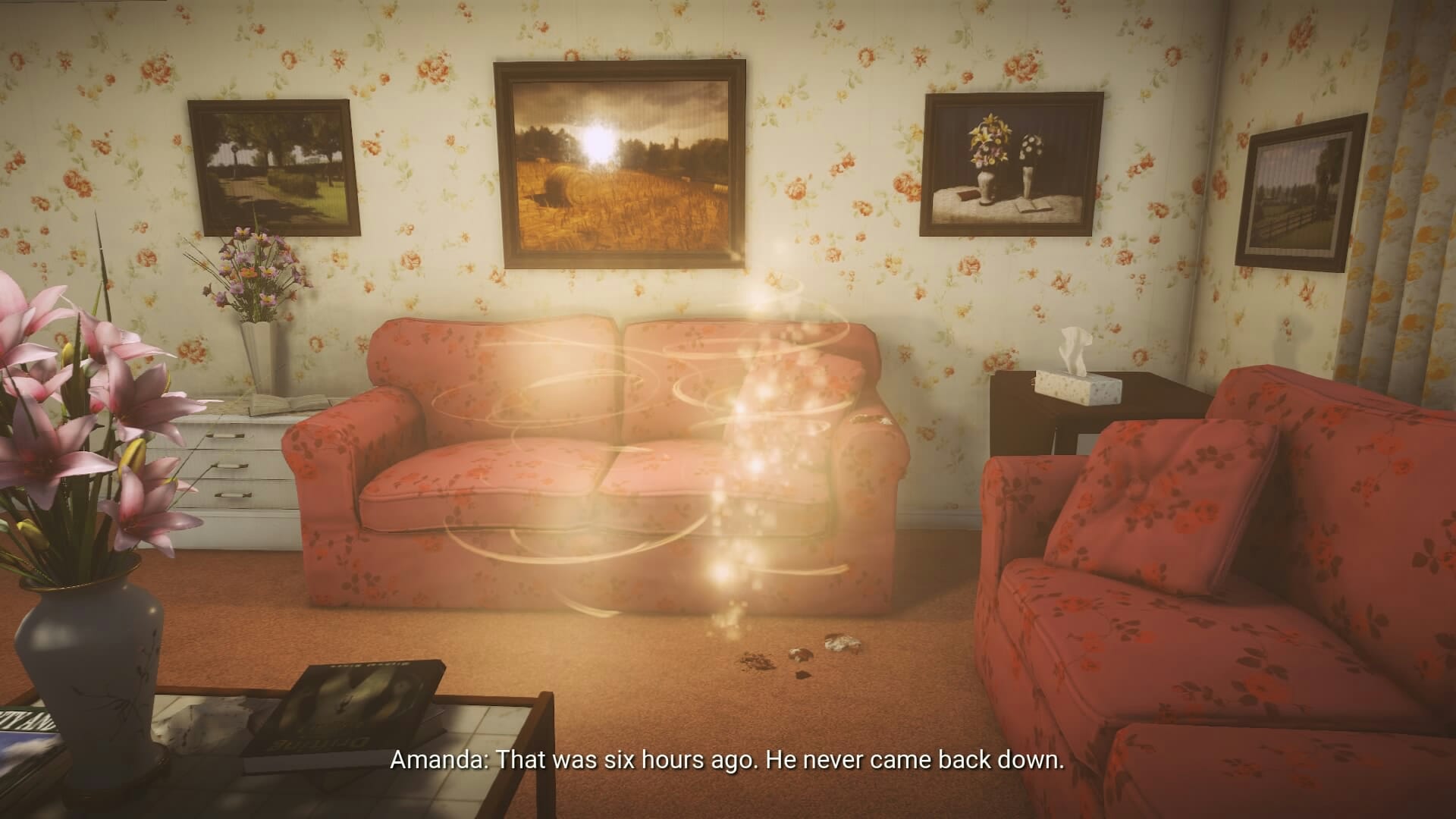

Grahame had the hefty job of establishing the somber tone that runs throughout the whole game while working on Barbara Foster’s house. It’s one of the first buildings players can enter and be presented with a character scene inside—a small flashback related to a specific character and location played out in light particles. This one, it turns out, is particularly harrowing, and Grahame had to make sure it both resonated and intrigued its audience. “This was a difficult task as the scene that plays out is not of the character who owns the house,” Grahame said. “It was important to visualize the owner (Barbara Foster) and use her background to juxtapose with the scene of a woman realizing her children have died.” Grahame created Barbara Foster’s personality by looking to classic British cultural touchstones such as the TV series Keeping Up Appearances (1990-1995), and its snobbish middle-class homemaker Hyacinth Bucket. As such, Barbara Foster became a conservative character in her 60s or 70s, which is reflected in the interior decoration. “Floral patterns cover the walls, the sofas and pictures of flowers and vases are all over the warm pastel colored environment,” Grahame said. This is then contrasted with bloody tissues that lie around the living room, where the character scene plays out, which were used to “suggest that something is wrong.” It’s not until the scene leads players upstairs that they can infer that the children must have died.

Barbara Foster’s house is representative of the balance that Grahame and the rest of the artists working on Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture had to consistently aim to hit. On one side of this balance was an effort to create a “classically beautiful aesthetic and idyllic environment” like those iconic landscapes painted by English Romantics in the 18th and 19th centuries. Think sun-drenched horizons and fields of windswept buttercups, perhaps the green leaves of a weeping willow drooping into a shimmering summer lake while families picnic on the nearby grass. Alongside this there was a need to strive for authenticity and plausibility to ground the characters and the game’s tragic narrative. “It was a rare and exciting opportunity for a games artist to include classically unique British moments and props into the game such as British architecture, foliage, vehicles, phone boxes, post boxes, graffiti, and other instantly recognizably British icons,” Grahame said.

“since her death, his house is in disarray”

To inform her efforts to hit that balance between these two conflicting sides—the romantic and the real—Grahame looked to classic English landscape painter J. M. W. Turner and German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich. “I like to look at artists that create emotion through their work in less explicit ways to understand how to create atmosphere and tone through subtlety,” Grahame said. “Turner and Friedrich […] both use light and color to create emotion through their work with strong contrast.” Following that lead, Grahame looked to capture the atmosphere of a location through color and environmental contrast, and the scene that exemplifies this for her involves the character Frank Appleton. “Through the game we discover that Frank’s wife died months ago, and since her death, his house is in disarray,” Grahame said. “The dirty, unkept house visualizes Frank’s dependency and his sadness for losing his wife. The contrast and realization of this comes only from the room she died in, which has been kept immaculate, untouched, and preserved. It demonstrates the depth of these characters. There’s an appreciation to understand and empathize, which makes their stories come alive.”

Thunderstorm with the Death of Amelia, William Williams, 1784

Frank Appleton is almost an archetype of British melancholia. He’s a stern farmer and family man turned inside out by the death of his wife. He has anger issues, but his attacks are mostly directed at himself: an anger at his incapability to deal with his personal loss. We last see him stood upon a hill overlooking his farmlands as bombs are dropped on them, ready to face death and rejoin his wife. It’s as if a realization of William Williams’ 1784 painting Thunderstorm with the Death of Amelia (in which two lovers meet at a hilltop for the woman to be struck dead by lightning), or the opening stanza of Gray’s Elegy, which goes:

“The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd wind slowly o’er the lea,

The ploughman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.”

But where Gray formed his sad characters in his own mind flowed through ink on the page, Grahame emphasizes that Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture was able to so superbly capture loneliness due to the strength of of the team behind it. “It is the whole experience that is a tool of artistic expression,” she said, “from the high level narrative themes, to the visually detailed worlds and the emotive soundtrack. Working collaboratively creates a cohesive and authentic final experience that can convey the story from different perspectives.” Working with a flat hierarchy and allowing everyone on the team to chip in with their unique perspective is what Grahame said encouraged communication and creativity in the game’s production. It succeeds, she said, as a work stitched together by multiple artistic visions. Which is appropriate given that Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture doesn’t capture the melancholy of just one person, but many, all of their stories woven into an environment marked by solitary yet connected deaths. It is a tapestry of the melancholy that runs through the English character and the varying artworks the nation has used to express it to the world over the years.

///

To learn more about the Kill Screen Festival and register, visit the website.