In Ethiopia, one game design professor believes that young girls hold the key

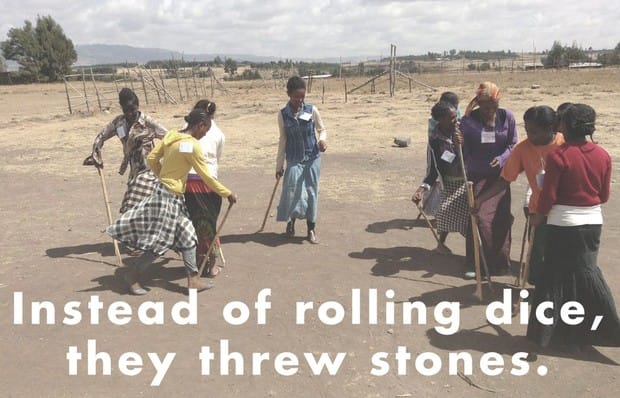

Instead of rolling dice, they threw stones. “To get random numbers, we’d pick three flat stones and mark them one, two, three,” she explains, “leaving the other sides blank.” This way, the Ethiopian girls Jessica Hammer had been teaching organic games to all winter could produce the rock-dice themselves and continue to play after she was gone. “If they don’t have access to a marker, they can use mud or clay,” she tells me.

A professor of game design at Columbia University, Hammer spent her tenure in eastern Africa in Addis Ababa and the rural province of Amhara, living out of hotels. As for the climate, “it was reaaaaally hot!” she says. Her daily activities included playing games with girls, teaching girls games, having them teach games to her. But she wasn’t frolicking in the grasslands for her own amusement. These game clubs were part of a cultural intervention program called Yegna (Amharic for “ours”), aimed at upping the status quo for adolescent girls age ten to sixteen. These are “games that change people’s lives,” she says.

Ethiopia is a country on the rebound. Though its recent past is checkered with civil war and genocide, the nation is moving in the right direction, in no small part due to Western aide. But if the country wants to evolve into a developed nation, it needs to keep the funds coming, and that requires a facelift to its sordid human rights reputation. Ethiopia has dropped big bucks into cleaning up its image, including attempts to elevate the status of women.

The hope behind girls clubs in Ethiopia is that learning to play and design games can be emancipating.

In parts of the world with far more equality, there has been a movement to get the fairer sex involved in computer sciences. Quite a few organizations are doing their part to empower female coders, including Girls Who Code and Girls Develop It. The hope behind girls clubs in Ethiopia is that learning to play and design games can be emancipating.

Before Jessica went to Ethiopia, she was already passionate about games. Now she’s passionate about using games to make a difference. “If I could teach the girls to have [game design] skills,” she says, “that’s the best thing I can do with my life.” She believes that games say magnitudes about the culture we live in, and if you change the way people play, you can change society. This is all too evident in the pecking order of Ethiopia’s communities, where girls have few rights, no clout, and often aren’t allowed to play. Hammer says the girls would hide when the boys came around to see what they were up to, and that the elders would lecture them sternly about being too old for nonsense as early as age ten.

If you change the way people play, you can change society.

What’s so important that ten-year-olds aren’t allowed to hold hands and skip in the sun? Growing up and starting a family, mainly. At that precocious age, some girls are already being treated like adults. Before long, they’ll be married and expecting children, which not only limits their prospects, but poses risks to their health. Part of the organization’s initiative is to encourage girls to make sound decisions about sex, but, also, just to stand up for themselves. Fifty percent of Ethiopian girls think that domestic violence is acceptable. Twenty-one percent are not allowed to have friends. Kidnapping opposed to courtship isn’t uncommon. It’s all pretty unthinkable.

Another problem; “rural girls aren’t supposed to speak up and have their voices heard,” Hammer says. So, one of the games her crew came up with was a riddle game, based on a local folk game, but designed to foster the confidence required to speak in front of a group. “The shyer girls would whisper into the ears of other girls, and those girls would speak for them, but the girls who did the whispering would be standing there, looking at the rest,” she says. For this game, they would draw words from a deck of cards, which contained positive concepts: trust, safety, friendship, confidence, resilience, courage. You can imagine it as a life-affirming round of Taboo.

You can imagine it as a life-affirming round of Taboo.

The approach was decisively grassroots. The game clubs were held out in the elements, in the forests, among the eucalyptus groves, and at school houses, which were small shacks and huts with benches and chairs inside. Running water was occasionally a problem. Once or twice, they had to use latrines. “You couldn’t wash your hands,” Hammer tells me, asking me to keep in mind that the girls at school are the lucky ones. (Many girls’ families refuse to pay the five dollars it costs to attend.) At least these institutions of education provide safe havens where the girls can play their rather fascinating native games, the majority of which don’t have names. The ‘bottle cap game,’ for instance, sounds joyously sophisticated, involving two teams, a carefully-stacked tower of bottle caps, and a ball to pelt the attacking team.

A few of the girls, Hammer believes, were natural-born game designers. She will never forget a girl named Meseret, a tall fifteen-year-old with short curly hair who carries herself with quiet confidence. “Her mind, her grace, her design sensibility,” she says, was everything she looks for in her students at Columbia. When the group was playing a math game, Meseret spoke up, and they would wind up playing many of her ideas in the coming days.

Later on, “under the eucalyptus trees,” Hammer relays, her voice growing wispy, “a bunch of boys came over to watch, and a lot of the girls just shut down.” They were worried about being seen playing. But Meseret stepped up, took a branch, waved it at the boys, and hissed at them. The boys all ran.

“We gave this girl the idea that she can change the rules to the game,” she says. Change the rules, indeed.

The Replayable Design team is Jessica Hammer, John Stavropolous, Meguey Baker, Giulia Barbano, Julia Ellingboe, Elizabeth Sampat, Malka Older, and Chris Hall. Photos by John Stavropolous.

Additional editorial support by Nina Freeman.