By powering her games with solar energy, Kara Stone isn't just making an environmental statement—she's unlocking new aesthetic possibilities in game design through conscious constraint.

High technology doesn't mean high creativity. In fact, sometimes the restrictions of a medium lead to the most creative solutions.- James Wallbank, 1999

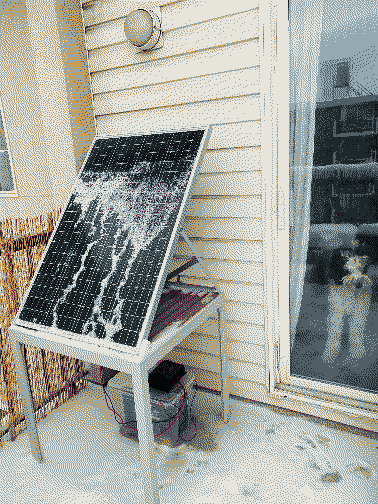

On a little balcony in Calgary, facing the legendarily sunny Calgary sky, sits a 150w solar panel. A small cable runs to the inside of the apartment, which is strung to a maximum power point tracking controller that manages the power flow of an even smaller micro-computer. A data card is installed inside the microcomputer and connects this elaborate setup to a web server. From that web server, from the sun to the screen, Kara Stone has generated enough energy to power a little world.

Solar Server is precisely as it sounds—a solar-powered setup to host low-carbon video games.

"I had always considered myself an environmentalist, but for a long time, I struggled meaningfully connecting that to my art practice,” Kara tells me. Having moved from Toronto, she’d fallen in love with “outdoorsy types of things” to complement ample time spent behind a screen. Like all of us wrestling with climate uncertainty, she wanted to explore how to express our collective anxiety through helpful things. “Beyond just making games with environmental themes, I wanted to create something with measurable, practical impact,” she says.

The conundrum for a new media artist, let alone a game-based artist, is reconciling the real material concerns of energy usage with a vibrant practice built on the contributions of the information computer technology industry. “High-tech artworks market new PCs. Even if they aren't meant to,” wrote James Wallbank in his Lowtech Manifesto in 1999. “Artworks that use new, expensive technology can't avoid being, in part, sales demonstrations. Part of the message [...] is ‘Hey, isn't it time for an upgrade?’.”

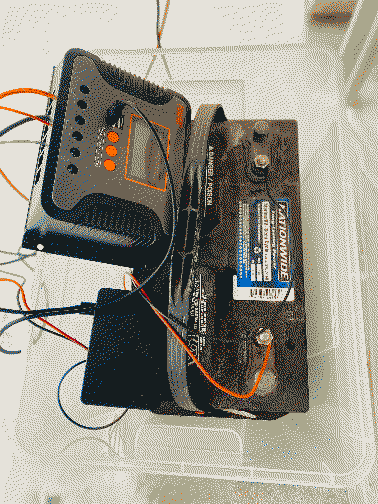

Stone's Solar Server setup

Stone felt trapped. "I was kind of stuck thinking that the the best thing I could do for the environment is stop making things.” This eco-fatalism has an allure, no doubt. Why not throw in the towel? But author Jonathan Franzen offers an out:

Keep doing the right thing for the planet, yes, but also keep trying to save what you love specifically—a community, an institution, a wild place, a species that’s in trouble—and take heart in your small successes. Any good thing you do now is arguably a hedge against the hotter future, but the really meaningful thing is that it’s good today. As long as you have something to love, you have something to hope for.

So, if games are good things worth protecting, what next?

For her 2020 game UnearthU, Stone only used found footage and existing materials rather than creating new content, describing it as having "an ethos of digital compost.” This approach opened the door to the philosophy of “permacomputing,” a nascent movement to promote a more sustainable approach to working with technology. Permacomputing aims to “give computers a meaningful and sustainable place in a human civilization that has a meaningful and sustainable place in the planetary biosphere,” writes Ville-Matias Heikkilä.

Echoing Franzen’s words, permacomputing also provides an optimistic view of the future. Heikkilä continues to love permacomputing because “it does not advocate ‘going back in time,’” he wrote. Yes, energy use needs to go down, but instead, it’s faith in human’s ability to find new solutions that will chart a path forward. “Very much the same kind of creative thinking I appreciate in computer hacking,” he .

Inspired, Stone set to work. The technical setup for Solar Server was straightforward: Stone mounted a 150-watt solar panel on her Calgary balcony, connecting it to a marine battery (typically used in boats) and an MPPT controller. This controller manages power flow between the panel, battery, and a Raspberry Pi microcomputer that serves as the web server. The hardware configuration is intentionally minimal, reflecting the project's environmental aims.

"I would consider myself an environmentalist,” she frets. “But in my art practice, it would only be themes of environmentalism."

Now, she needed to make a game.

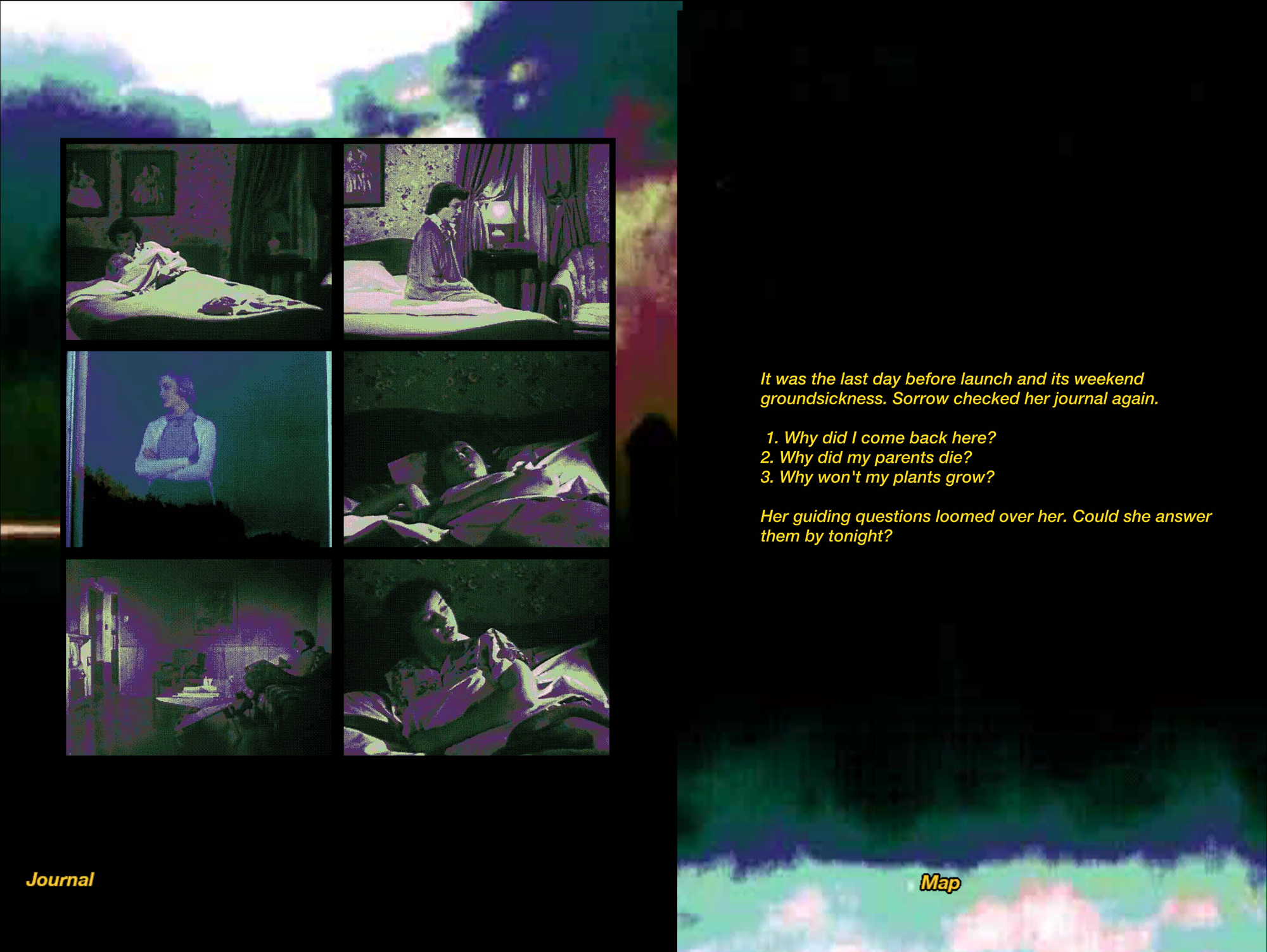

Known Mysteries is the first title for Solar Server. Unlike Stone’s sunny disposition, it is a decidedly pessimistic work. In near-future Canada, residents have given up on saving a planet spiraling into its demise, and lotteries send inhabitants to life in the stars. A woman named Sorrow sets out to uncover one last enigma surrounding her parents' death and the fossil fuel company behind it.

Setting up the physical components was relatively simple for Stone, who had prior experience with physical computing. Configuring the backend web server proved more challenging, requiring her to learn new technical skills. Pulling from experiments with Low Tech Magazine’s solar-powered website, her server runs as a static website to minimize computational demands and resource usage, drawing on practices from early computing when storage constraints were commonplace.

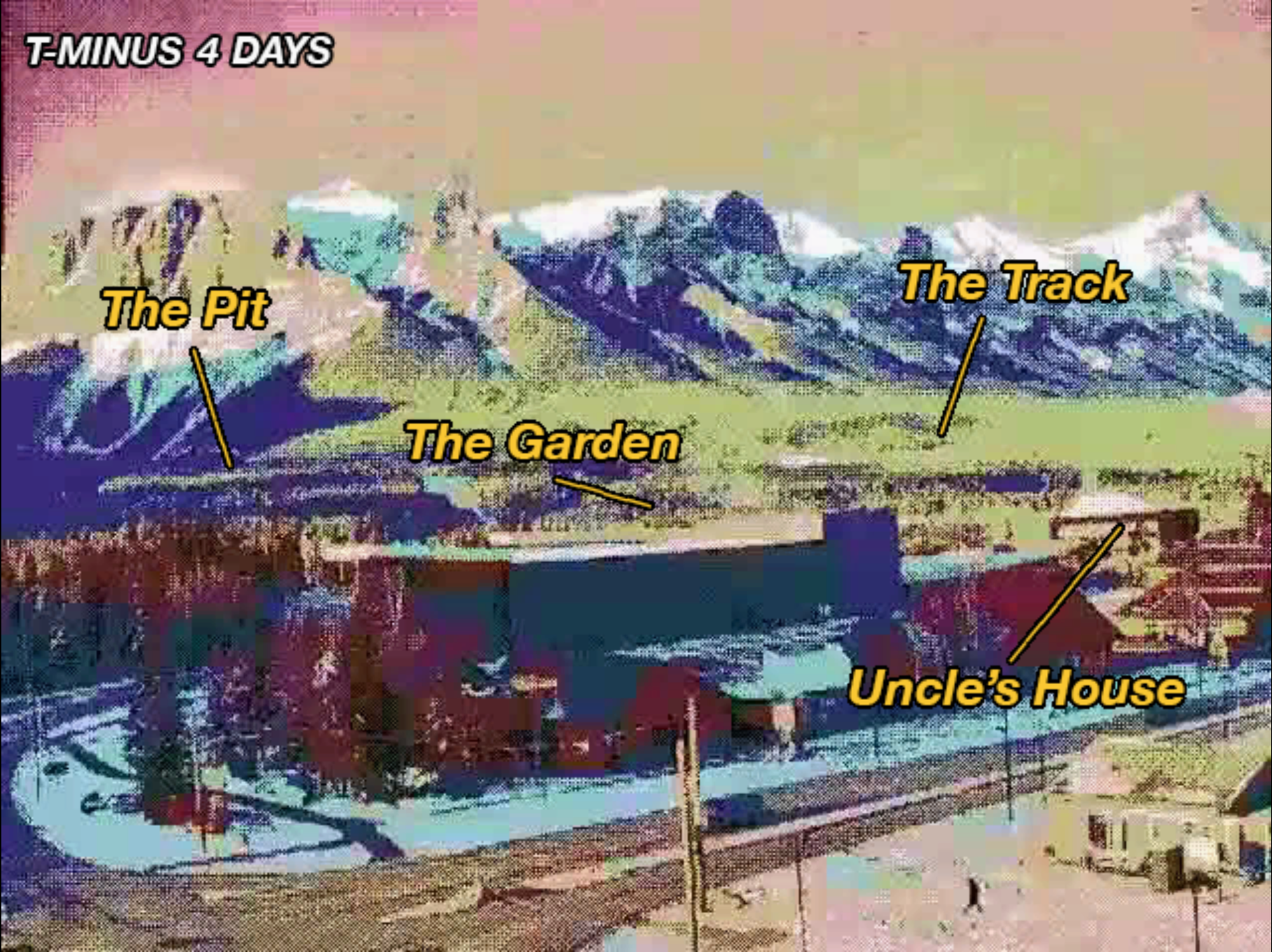

First few minutes for Known Mysteries

Stone's approach prioritizes concept over conventional game design elements, an approach pulled from her early days as a film editor. She explains, "I've always been interested in concept [...] rather than perfecting the three-arc story structure, the best camera or the most beautiful shot." This conceptual focus shapes every aspect of her work: "The image should match it. The narrative should match it. The process should match the concept." Known Mysteries’ approach opens to conceptual departures from games that yield unique experiences for players.

The first is obvious. The game looks different.

Stone's environmental consciousness shapes both her creative process and output. "The aesthetic of it was all handcrafted and scanned and digitized," she notes, describing her approach to game creation. The dithering video is a deliberate distraction, where its resolution is foregrounded in a world of high-resolution devices. “I wanted to point to that aesthetic that this is a process that I was doing and trying to make it as small as possible.”

Found footage before dithering is added.

The second layer of experimentation is time itself. Stone started thinking about how we conceived of time-based gaming work with Ritual of the Moon in 2019, a 28-day-long multi-narrative game exploring loneliness, power, and healing. Over a lunar cycle, players engage with a witch exiled to the moon, participating in a series of contemplative interactions that blur the line between play and personal ritual. Each brief session involves arranging objects on an altar, tracing objects, and receiving mantras—acts that echo ancient spiritual practices and contemporary mindfulness exercises.

Gaming's current approach to players’ time is fraught. There are clever uses: Contrast Animal Crossing’s clever use of the device’s internal clock to trigger specific events. And then there is the current approach of live-service games like Fortnite's desire to pull you in for every moment and never let you go. "This is an unspoken extractive approach in many types of digital media,” Stone bemoans. “The expectation is that you're supposed to spend a very long time with this thing.”

Known Mysteries' approach to time reflects Stone's same care for the environment. The game is not long and can be played in one sitting. Stone dutifully divided it into three chapters for environmental reasons, mapping out the chapter on pen and paper on her living room floor. The result is a synthesis of concept and execution Shethreaded through her work: lower server load and electricity usage while respecting player engagement.

This perspective reframes limitations not as obstacles but as opportunities for innovation. She emphasizes that these constraints don't diminish the work: "I don't view Known Mysteries and future projects on Solar Server to be lesser than."

“Maximalist techno-aesthetics” is the idea that perpetual growth and infinite resources are present as an absolute good. “Increasing density of information for its own sake: more pixels, more detail, more fidelity, and more connectivity equals more potential,” write Aymeric Mansoux, Brendan Howell, Dušan Barok, and Heikkilä (one permacomputing's principal voices above.) The problem is that this approach emphasizes new tools, techniques, and consumption, which puts pressure on art and design. This is unsustainable for both the planet and for artists. Stone shares that approach: Her work demonstrates a deep respect for human constraints, rejecting that games should be "for all things for all peoples."

However, games present a conundrum for artists working with them as material. While video games run alongside the development of late-stage capitalism, the history of games predates the advent of computers. Moreover, some new human experiences and genres would not be possible without introducing new technologies. Battle royale games emerged when technology finally caught up to our collective desire for massive-scale digital competition–advances in networking, server architecture, and graphics technology enabled dozens of players to share dynamic moments in ways that early multiplayer games, limited to intimate player counts, could only dream of. As they are always amorphous and growing into spaces opened by new technologies, games are rare examples of where the promise of more has generated something novel. Who wouldn’t trade games over social media?

However, the operative word is “for its own sake.” Because we can, it does not mean that we should, and the aesthetic appeal of permacomputing opens the door to considering those ecological constraints as part of a work’s quality. Mansoux et al. encourage a syncresis: the aesthetics of the thing should be deeply intertwined with the making of the thing. "Permacomputing [is about] systems of relations, sensing and making sense [of] the process of making and working around and with computational constraints,” Mansoux et al. write. Tldr; you are what you eat.

The return to constraint is welcome. The same self-imposed or external boundaries that generate the novelty of tape edits and found footage form a central part of Stone's practice. She observes, "We're always working with constraints all the time, and whether we're like recognizing them or not like we are, and I think they can be creatively inspiring."

Ironically, Stone’s work is more consistent with the genealogy of games because she resurrects an era when there wasn’t enough compute. In Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost’s Racing the Beam, the authors outline the myriad ways that early computer programmers worked around the limitations of the Atari 2600. The system's notorious hardware constraints became, unexpectedly, a catalyst for computational creativity. Take the VCS's limited RAM—a restriction that would seem crippling by today's standards. Developers responded by leveraging the system's built-in playfield symmetry to essentially get two screens' worth of data for the price of one, a technique prominently featured in Combat (and later refined in countless other titles).

Perhaps most remarkably, Atari programmers transformed one of the system's most severe technical constraints—the need to draw graphics line-by-line in sync with the television's electron beam—into an opportunity for technical artistry. Through a technique known as sprite multiplexing (essentially reusing sprite data in different screen positions), developers created the illusion of far more objects on screen than the hardware officially supported. Bogost and Montfort write:

Not because it was a powerful computer, so much was possible on the Atari VCS. It wasn’t powerful at all. Instead, so much was possible because the machine was so simple. The very few things it could do well—drawing a few movable objects on the screen one line at a time while uttering sounds using square waves and noise—could be put together in a wide variety of ways to achieve surprising results. [emphasis my own]

The tension between commercial viability and artistic integrity is evident in Stone's decision-making process. "I would have to have my art practice look different because it would be about what I think is good and what I want to make," she reflects. "But also, what do I think audiences want to see and buy? I didn't want to sacrifice my practice."

It turns out that you don’t.

All quotations from Kara are edited for style and grammar.