Everything in its right place: a Pokémon Omega Ruby Review

I’d argue that videogames have the most complex relationship to repetition of any artform. Poems of a certain kind repeat whole lines, songs repeat choruses and leitmotifs, serialized TV suffers from self-imposed amnesia, and Hollywood essentially re-releases its biggest blockbusters every two years. Repetition is natural, maybe inevitable, in art. But none of these forms loop back on themselves so often as games do.

Here’s the first loop: you can’t talk about a Pokémon game in isolation. When you talk about one, you’re already talking about every game before it. And if tradition holds, it suggests the direction for every game after it. This is broadly true for other serial games, but fundamental to Pokémon. After all, there are porous boundaries between individual entries in the series: overlapping geography, monsters, gym leaders, characters, and so on. Old games get a fresh coat of paint every few years to bring their monsters into the current generation, new games incorporate pieces of the old, beckoning to nostalgia. Each builds off of and feeds into the others. Pokémon is an ouroboros.

Pokémon is an ouroboros.

At its broadest point, Pokémon Omega Ruby is about redoing. The designers have remade a ten-year-old game in a ten-years-newer engine, with the baubles developed during the intervening years hung on the sides. You redo battles, re-explore routes, re-fight gym leaders. You’re vamping on themes but it always ends with that same resolving chord.

Remakes matter for people who haven’t and otherwise wouldn’t have experienced the thing being remade. If you didn’t play Ruby in the early 2000s, Omega Ruby is unequivocally the best way to experience it. It breaks from the preceding games by casting the player’s (historically absent) dad as a gym leader, tacks on the Mega Evolution concept from 2013’s Pokémon X and Y, and offers tons of little to-dos that help build up your team. You fight Team Magma, who, to your slackjawed surprise, are up to precisely no good. It’s Pokémon Ruby improved in every measurable way. But you can’t shake the feeling that it’s also an unending gyre of game loops: a remake looping back to an earlier game that was itself comprised of loops, opening up a cylindrical maw that spirals all the way back down to the first time you woke up in Pallet Town and chose Bulbasaur or Charmander or Squirtle, if you can bear to look that far down.

The good news is that Omega Ruby is aggressively self-aware on this front. When the game first starts up, it reads like something’s wrong. You’re looking at the screen you expected to see, the one where the professor tells you about the world of Pokémon, asks your name, fails to remember the name of your soon-to-be rival. But the image is pixelated and unstable. It looks like a bad port, not the high-def remake you were promised.

As soon as this concern has had a second to settle in, the camera pulls back to reveal the border of a screen, hands, arms. You’re in a first-person view, and your character’s holding a GameBoy SP (the clamshell one), playing the beginning of Pokémon Ruby to welcome you to the beginning of Pokémon Omega Ruby. You smile. You’re in on the joke. Even the people in the world of Pokémon play Pokémon. And then you take another step back, seeing yourself holding a 3DS holding a game holding a character holding a game holding a character playing Pokémon. You’ve had your eyes peeled open, been forced to look all the way down that familiar rabbit hole, and you know it’s time to go back down.

You can’t shake the feeling that it’s also an unending gyre of game loops.

At this point, nearly twenty years after the first game came stateside, we see Pokémon for what it is: a perfectly cut diamond that the jeweler nevertheless re-cuts each year, taking advantage of new technologies, and accounting for evolving ideas of what a diamond ought to be. But cutting from the same diamond year after year means that the jeweler’s also shrinking it down, discarding the exterior, exposing the interior. Let’s put it this way: Pokémon does not obey the less-is-more mantra of the flash-fiction writer or the minimalist designer refining her product to its essential form. It’s more like the seven re-cuts that made Blade Runner: Each inflects something slightly different about the narrative from the same source material, but watching them all becomes more reductive than expansive. The best way to see Blade Runner is to just watch The Final Cut. But understanding why that’s the best version means you have to look back through the archive to see the missteps, the bad edits, the omissions, the additions, the revisions.

The problem with a finely honed system like Pokémon is that, unlike Blade Runner, there’s no uncertainty, no ambiguity, and, at its most pernicious, no challenge outside of competitive play. The characters are inoffensive and monochromatic. The environments have been so thoroughly kid-proofed that they don’t even offer a sense of staged discovery. Maybe I’m just burnt out on these loops after seventeen (!) years of getting to know the game. But I think there’s something else at work here.

Maybe I’m just burnt out.

In videogames, we have to contend with the “core loop”—that series of repeated actions that contribute to progress within the game. In a game like Zelda, it’s the transition from overworld dungeon to the acquisition of a new weapon and back to the overworld; in arcade games like Pac-Man, it’s the insert-coin-to-continue life system; in a strategy game like Age of Empires, it’s the unit-deployment-and-upgrade process. If you happened to see it, the other week’s South Park explained the (sinister) core loop at the heart of free-to-play really well.

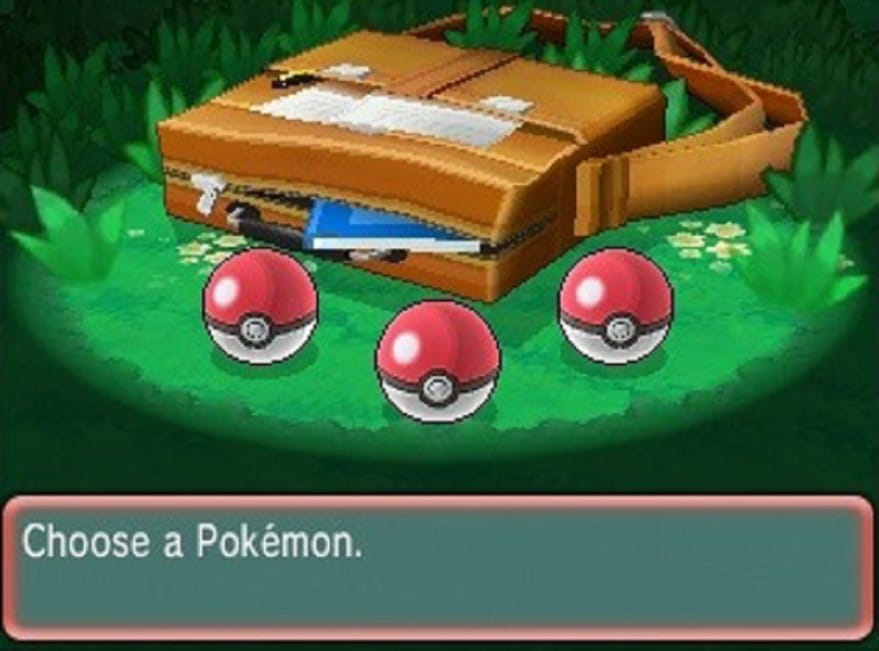

You can make a strong case that Pokémon has survived unchanged for as long as it has because of its core loops. From a distance, the game looks like a series of concentric circles. The most fundamental loop is the battle. Same music, same layout, same progression every time: life bars fall, experience points rise, occasionally your monsters evolve. Then, at the next level out, there’s the exploration loop, which consists mainly of battles, items to grab, and quick return visits to the Pokémon center before heading back out into the wild. Fighting your way through these thickets eventually leads you to a new city with a new gym where you run through the trainers, fight the leader, get a badge, and collect another important Thing without which progress is impossible/the world will end.

The loops described above exist within the much larger Be-The-Very-Best loop. Everything you do in Pokémon—from the individual battle all the way up to the new parts of the map you unlock through exploration—brings you a tiny bit closer to that coveted Elite Four Champion status, the defeat of this game’s Team Rocket equivalent, the capture of the legendary Pokémon on the game box. Not only is the game’s end always in sight, but the way everything you do in the game contributes to that end is always clear, too. Time spent in Pokémon triggers that state of blissful productivity Jane McGonigal describes in Reality is Broken: Almost nothing you can do here wastes time since everything you do brings you closer to success. It’s the covert and seductive message at the heart of many games: “Stay a while. You’re good at this.”

Considered in this way, Pokémon looks kind of like a Le Corbusier chair: everything in its right place, nothing without purpose, all parts contributing toward a clear, singular end. Then again, also like a Le Corbusier chair, it’s a lot more comfortable in theory than in practice. These loops sustain us and have been tweaked to their best form yet in Omega Ruby. Yet they can’t help but remind us that we’ve done all this before and will do it all again. That, in a few years, you’ll start a new Pokémon game playing a character who’s playing Pokémon Omega Ruby on a clunky old 3DS, a knowing wink to the game that came before and a subtle assurance that, here too, everything’s as you’d expect it to be.