Facebook’s looking to streamline your next breakup

I started dating when MSN Messenger was still a thing and started breaking up in the era of Facebook, which was a good system right up until the moment that it wasn’t. That last comment is probably a fair description of all relationships. Social media did not create the awkwardness of breakups, but it did lengthen the gauntlet through which the newly single must run, and running is hard when all you want to do is stay in bed with Netflix and a tub of ice cream.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y8FuwUhAfUY

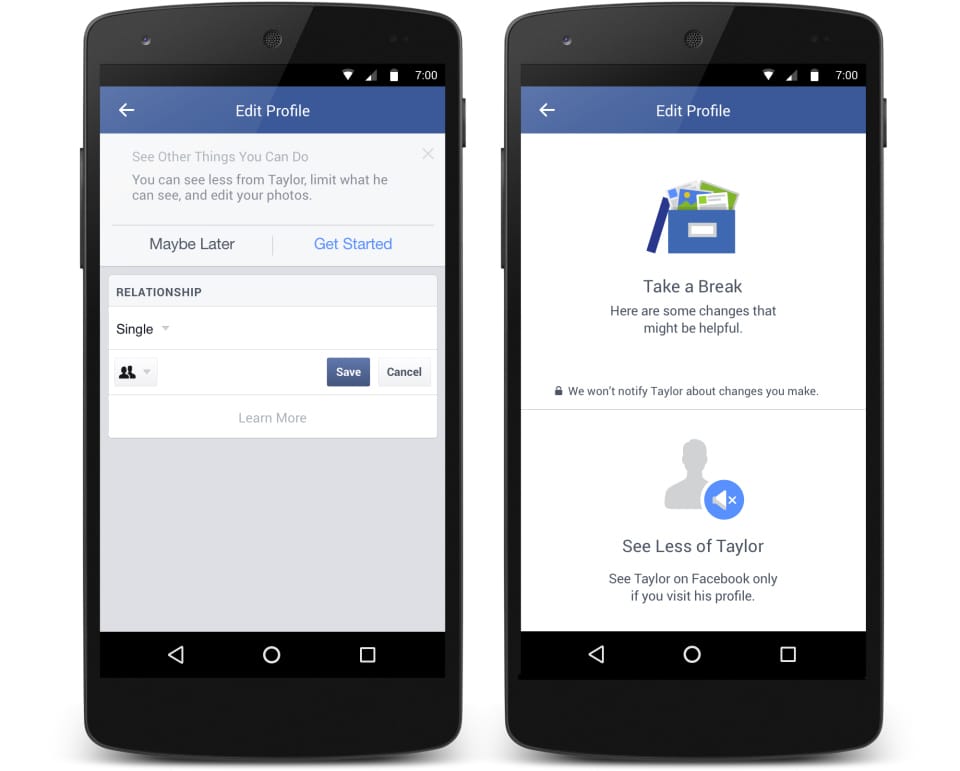

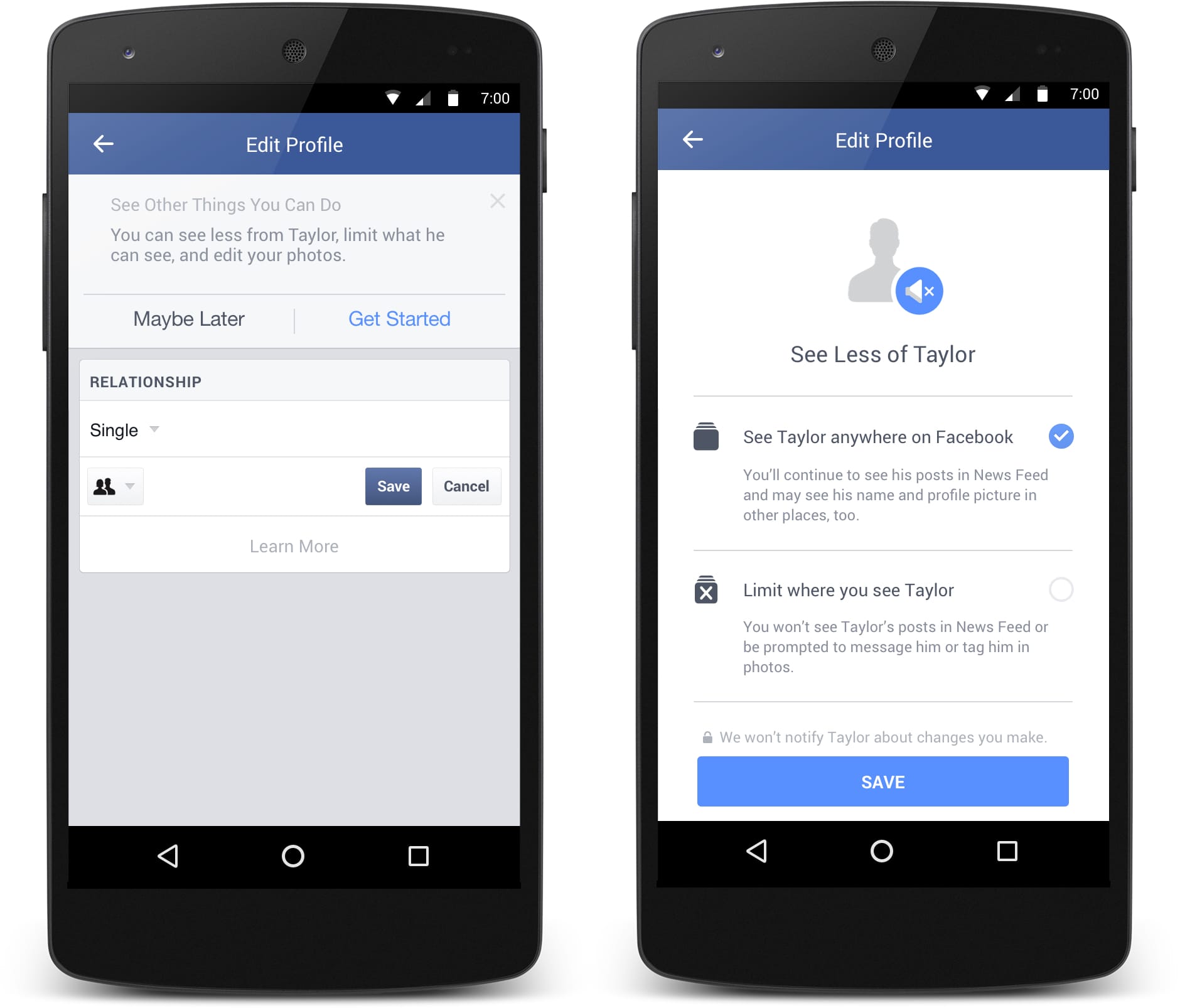

Facebook has apparently decided to do something about this 21st century problem. In a blog post published last Thursday, Facebook product manager Kelly Winters explained, “we are testing tools to help people manage how they interact with their former partners on Facebook after a relationship has ended.” To that end, Facebook users who exit relationships will be offered tools that will allow them to see less of their ex, ensure that former flames see fewer of their posts, and un-tag photos of the formerly-happy couple. “We hope these tools will help people end relationships on Facebook with greater ease, comfort and sense of control,” Winters writes.

Many moons, dates, and Facebook product updates ago, I parted ways with my partner of two-and-a-half years by mutual assent. “David is no longer in a relationship,” suddenly appeared in the newsfeeds of hundreds of putative friends. The only thing I remember about the evening in question is that one friend, whose connection with me remains something of a mystery, replied “Awwww, you two were like peanut butter and jelly.” Thanks, I guess?

The advertisers would rather you not be too miserable to log on.

What does one say in reply to such a comment? It is, on the one hand, the platonic ideal of a Facebook comment: brief, positive, and anodyne to the point of being impersonal. In any other context, it would be perfect. But thirty minutes after breaking up, it grates. This problem can either be solved by rooting out specific situations that are at odds with the ideal Facebook comment or by changing the definition of a good Facebook comment.

Is it any wonder that Facebook chose the former option? Better to weed out the occasional moment of incongruity than to change the platform’s entire tone. This act of kindness, like all acts of kindness, can quickly become oppressive. There will now be fewer reminders of your pain sandwiched between uplifting videos and ads. Don’t forget the ads. That is ultimately what this is all about. The advertisers would rather you not be too miserable to log on. They’ll still sell you dating services, naturally, but they don’t want you feeling too down. This may be a fair price to pay for not having to see your ex’s face for a little while, but it is unmistakably a transaction.

Facebook’s new breakup tools are but the latest case in which the company’s products have awkwardly intersected with its vision of wall-to-wall positivity. A little over a year ago, Facebook rolled out “year in review” videos in which a series of pictures from the previous year were compiled alongside cheerful graphics and music. Like everything else, this was a good system right up until the moment that it wasn’t. The most obvious shortcoming of this system was identified by Eric Meyer, who logged in to Facebook one day and was treated to a “Year in Review” ad featuring a picture of his daughter who had passed away during the year. Meyer came up with a term for this sort of technological mishap: Inadvertent algorithmic cruelty. He wrote:

And I know, of course, that this is not a deliberate assault. This inadvertent algorithmic cruelty is the result of code that works in the overwhelming majority of cases, reminding people of the awesomeness of their years, showing them selfies at a party or whale spouts from sailing boats or the marina outside their vacation house. …

To show me Rebecca’s face and say “Here’s what your year looked like!” is jarring. It feels wrong, and coming from an actual person, it would be wrong. Coming from code, it’s just unfortunate. These are hard, hard problems. It isn’t easy to programmatically figure out if a picture has a ton of Likes because it’s hilarious, astounding, or heartbreaking.

So once again, we have the question of whether you tweak the product or the broader context. If the default unit of a network is positivity, if engagement normally equals positivity, this sort of awkwardness will always live at the edges. The chosen solution, with breakup tools or with Facebook’s promise to Meyer that they would do better, is to fix some of those edge cases. This is a laudable goal, but you can’t hold back a flood with your fingers. As with nuclear war or a breakup, the solution to this sort of technological problem is a sort of détente in which a certain amount of negativity is allowed to permeate the social network’s bubble. Moments of sadness are only calamitous outliers because they are constructed as such.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8UhONY3-1os

Yet change to the underlying context remains largely off the table. Instead, we’re in for round after round of fixes around the edges, each of which highlights the edge cases that go comparatively unaddressed. Breakup tools are nice, but are they really more important than more powerful tools to deal with abuse? Perhaps not, but they may well be more monetizable. In this respect, the various attempts to smooth out a social network’s edges are often the clearest indications of where its central priorities lie.