Falling through 100 million stories in Gravity Rush: Remastered

Gravity Rush (2012) director Keiichiro Toyama didn’t choose horror, it chose him. His first game as director, Silent Hill (1999), was assigned to him by his bosses at Konami. A stranger to horror as well as a self-professed scaredy-cat, in order to find his feet Toyama turned away from schlock and gore and towards those softer influences that did appeal to him: occult practices, mystery stories, and evidently enough, the work of David Lynch. Silent Hill’s thoughtful, ambiguous atmosphere may have gone on to define survival horror, but it also went on to define Toyama’s career. Which is why Gravity Rush, with its cartoonish sensibility and playful atmosphere was something of a curveball when it released on the PlayStation Vita in 2012. Beautiful and ambitious, it suggested a grand vision for a portable game, and an unlikely outlet for a reputed horror auteur. Somewhat of a critical success at the time, Gravity Rush has since been granted a sequel on the larger canvas of the PlayStation 4, as well as a full remaster. Buffed to an attractive sheen by specialists Bluepoint Games—responsible for both the Ico and Shadow of the Colossus remasters (2011) as well as The Nathan Drake Collection (2015)—Gravity Rush: Remastered is a vote of confidence in Toyama’s vision, and an attempt by Sony to widen the game’s audience. It works: even after four years, its distinct gravity-shifting, which sees protagonist Kat forever falling across its floating city, retains a sense of newness. But it is the game’s multi-layered, ornate city districts which are its most magnetic aspect. And it is in those densely packed towers that the game’s unlikely origins can be found.

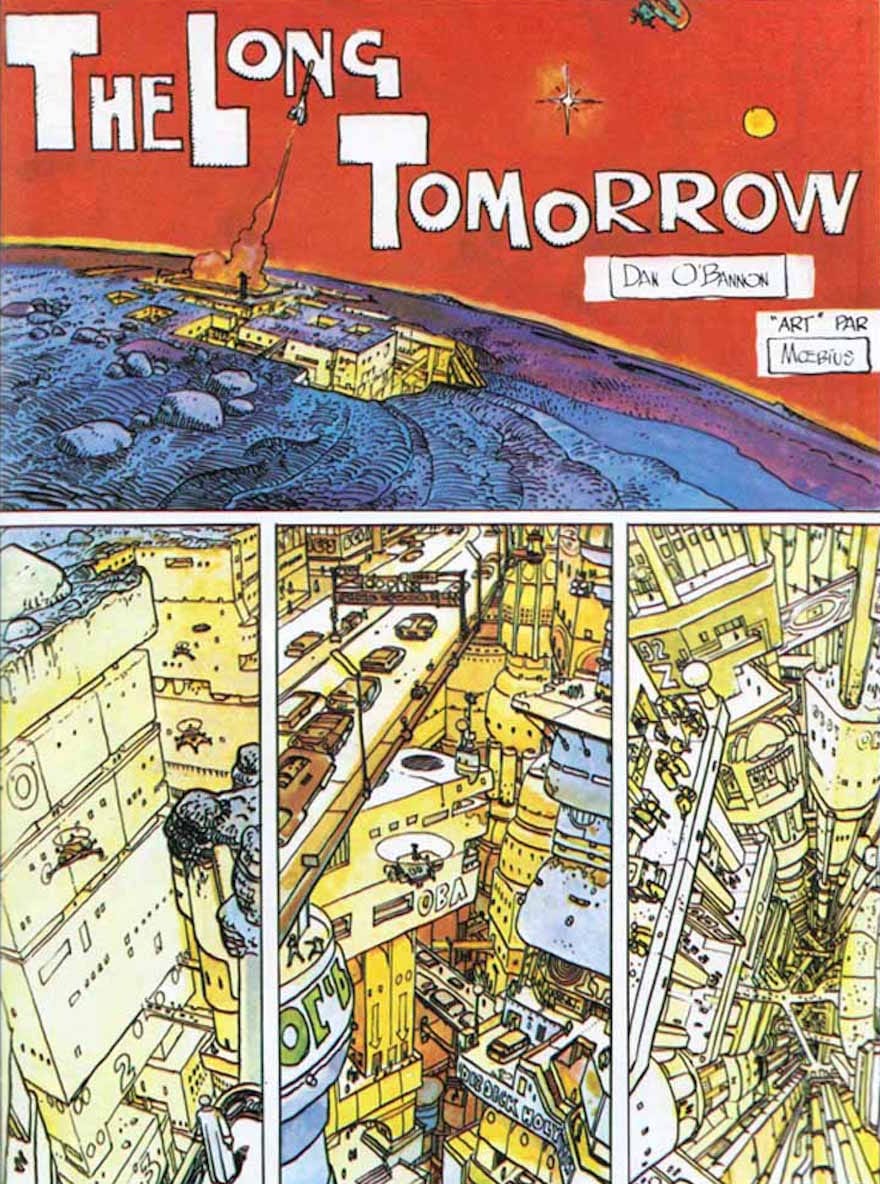

As a student, well before Silent Hill, Toyama was fascinated by the bandes dessinees of the 1970s, those French comics that found their way around the world among the pages of magazines like Metal Hurlant (or Heavy Metal, in its latter American form). Filled with precise line work and loose, bright colouring, these wildly inventive science-fiction stories and psychedelic trips had a unique influence on a whole generation of artists and writers. Jean Giraud, known by his pen-name Moebius, might be considered the most influential among them. In fact, his short graphic story, The Long Tomorrow (1975), created with Alien (1979) writer Dan O’Bannon while they were doing preparatory work for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s never-to-be-made Dune, has an almost unbelievable legacy for such a little known work. Cited by three of the godfathers of science-fiction, it has been named as a key influence by Katsuhiro Otomo for his epic Akira (1988), by William Gibson for the textures of Neuromancer (1984), and by Ridley Scott as fueling the rich visual language of Blade Runner (1982). Such a collection of names and works represents high praise for what is a 16-page graphic short, a succinct blend of noir detective story and urban sci-fi with a taste for the surreal. Despite its age, and the fact that its visual language has been strip-mined for ideas, it’s still possible now to see why it was so influential. Otomo called it “dirty,” Scott labelled it as “a tangible future” of “cities on overload,” and Gibson referred to its visual texture as “density” and “perceptual overload”. What each of them found in Moebius’ work was an analog for a changing world, a hyperactive layering of images and frames. The final line of The Long Tomorrow is “There are 100 million stories in this city, this was twelve of them”. A pun on a classic noirish line, and a reference to the height and depth of Moebius seemingly endless, dirty, and dense city.

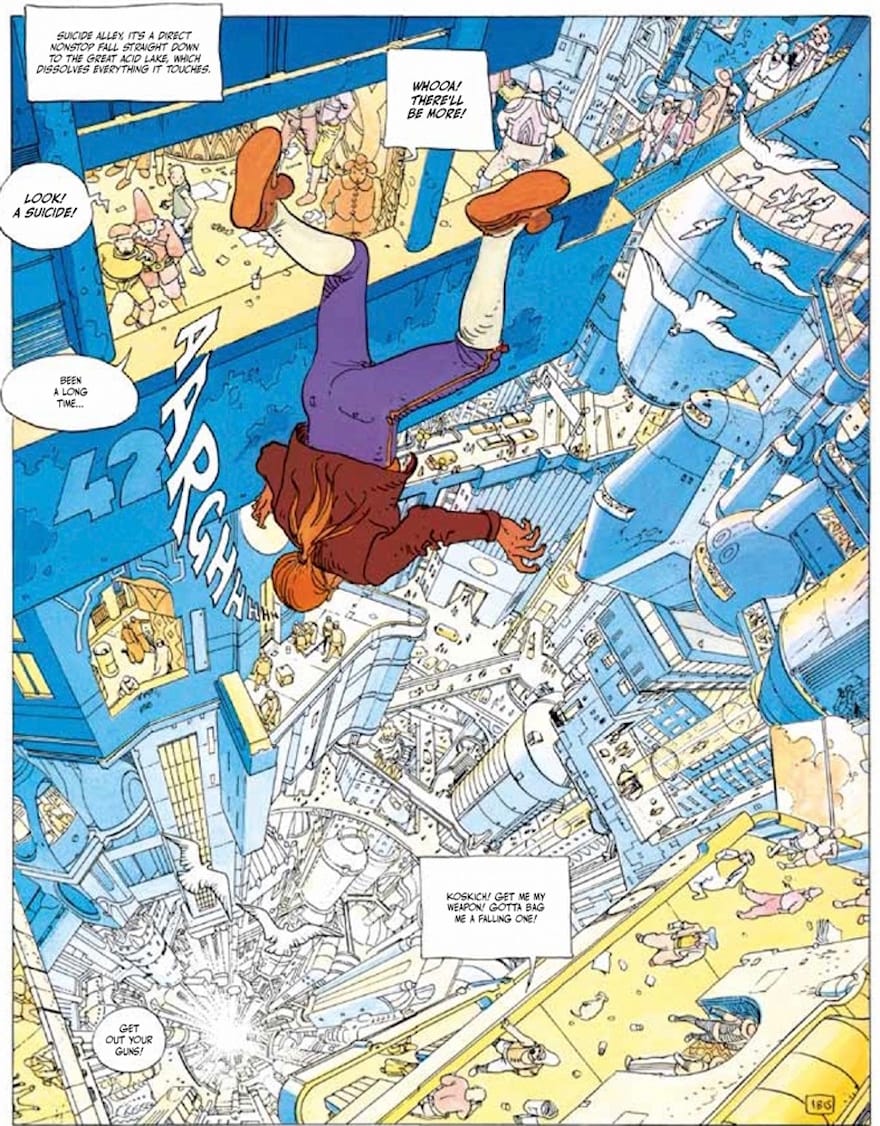

a death-defying fall

Yet Toyama saw something different in Moebius’ work. Something that is as equally present as the density and the dirt. He saw the romance, the scale, the Parisian belle-epoque style that lay just beneath the surface which, when washed clean, would bring forward something other than those stygian cyberpunk cities. After all, Blade Runner, Akira, and Neuromancer took the grand visions and colourful pulp of ‘70s science fiction and fed it into an ‘80s atmosphere of grunge and chunky technology, layering on the dirt of the street and the struggle of those who lived there. Looking at Moebius’ work in the ‘90s Toyama saw instead its optimism, its sense of wonder and scale, and the beauty of its ornate linework. Moebius, too, followed this path, his work drawing away from ugly urbanity towards a colourful and luxurious future. The Incal series, perhaps Moebius’ greatest work and a clear development of The Long Tomorrow’s hardboiled future, charts exactly that path. Beginning with the similar set-up borrowed from the work of noir writers like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, it accelerates out of the densely layered city towards a universe of surreal landscapes of crystals and prisms, imbued with the bizarre mystical hallmarks of its co-creator, Alejandro Jodorowsky. This is the Moebius that Toyama brings to the fore in Gravity Rush and its remaster. Almost garish colors back its grand city-islands, which buzz with a bright sense of life. Illegible script flowers atop beautiful art deco towers, while Parisian rooftops are multiplied and layered in impossible formations. And perhaps the most startling connection is the viewpoint that Toyama chooses for the player to experience this setting—the dramatically converging perspective lines of a death-defying fall.

If you turn to the second page of The Incal you find the inception of Gravity Rush, right there, nestled among the panels. John Difool, the private investigator and protagonist of The Incal is plummeting face first into a panel rich in detail, a city of overlapping walkways, ornate skyscrapers and a festering, glowing sense of life. As it recedes down below Difool, the linework of the city takes on an increasing simplicity, until it resolves into a handful of sketched shapes, and then at the lowest point, blank white. It’s an image that draws you in, as your eyes rehearse Difool’s fall again and again, each time picking up on new details as you scan the city from highest peak to lowest depth, from the pile of newspapers outside a door, to single points of distant passersby. This often imitated panel is both The Incal’s most resilient image, and Gravity Rush’s most explicit connection to Moebius. In fact, this image almost feels like a design document for Gravity Rush, giving it both its setting and its mode of locomotion. That’s what Toyama understood so clearly, that Moebius’s iconic dense cities were not just a collection of richly layered stories, but a perspective too.

This perspective is a difficult one to tire of. In Gravity Rush, it’s easy to find yourself climbing again and again to the edge of the tallest and most ornate tower just to throw yourself off, slipping between walkways and through gaps on the way down. The game’s gravity shifting, along with its floating city-islands mean that you can bisect the city, cutting through it at any angle. These trips are rewarded too, with new angles constantly revealing themselves, as hollowed out interiors are found to be filled with terraced slums, and crisscrossed pipes reveal hidden passages hundreds of flights of stairs below street-level. It’s often difficult to resolve these dizzying angles into a single city, and returning to the leafy square where you started your journey is as much of a surprise as any other. Even at pedestrian pace, Gravity Rush’s city seems to reveal layers and layers of hidden depths, from food stalls to the mix of characters you share the street with. To travel like this is to be defined by a vector, to simply choose a direction and then fall into it for as long as you can stand. It redefines the city as an object, one where each surface can be touched, each direction followed to its conclusion. In its movement Gravity Rush allows you to step lightly from every rooftop, to find by falling. To bisect the city, surround it, touch it, yet never fully conceive it. This city asks you to fall into it, eternally, like Difool tumbling head-first into Moebius’ linework, revealing a future that would be realized elsewhere by other artists with other aims, but carrying the same dizzying sense of forward momentum.