The Civilization series of games moves in cycles. On October 30, 2001, Civilization III was released; October 25, 2005 brought Civilization IV; the latest incarnation of the series was released September 21, 2010; and now Civilization VI arrives on October 21. There is a wistful sense of loss in this pattern—after a spring and summer five years long, the massive canopy of the previous Civilization game fades away to make room for the next, bigger, and hopefully better incarnation.

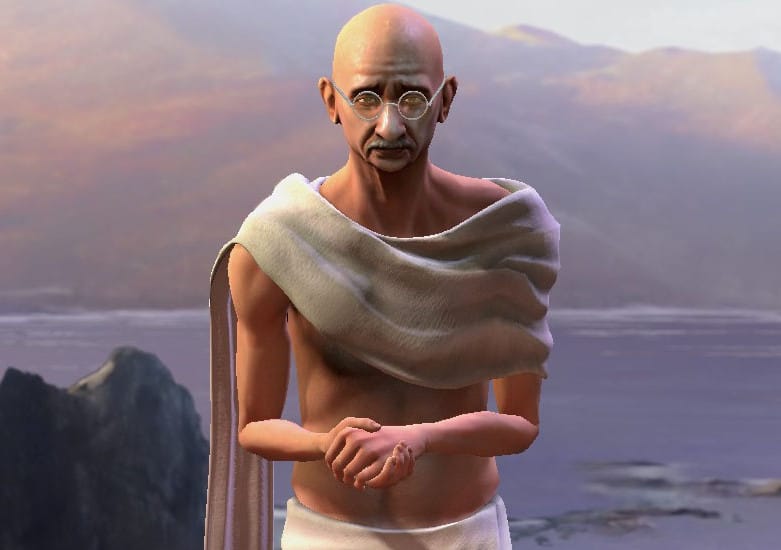

But this is the wrong metaphor. The Civilization series is concerned with civilization: with cities, with growth, with increasing cultural and material complexity over time. Each game suddenly appears on top of the previous one, like one of their in-game Wonders. It’s a series that repeatedly builds upon itself, its past evinced in the strata beneath the current layer. Gandhi’s traditional propensity for nuclear wars is the best example of this sense of tradition. The joke goes something like this: In the original Civilization, a value between one and 10 was assigned to each AI’s belligerence. Gandhi was given the lowest possible value—a one. This introduced a problem later on in the game, when a technology was unlocked that lowered every AI’s belligerence score by a few points. Rather than reducing Gandhi’s to zero, the code rolled back to the highest possible value: 255. So, at a predictable point in the game, Gandhi would transform from peaceful partner to a frothing, belligerent maniac who was dozens of times more violent than any other AI. What started out as a bug became a feature: every instance of the character, in any Civilization game, will go literally ballistic when they’ve unlocked nuclear weapons.

The list of additive innovations goes on. Civilization IV introduced quotes associated with each technology (narrated, originally, by Leonard Nemoy), which carried on into later games. Recurrent civilizations with recurrent leaders are other artefacts whose presence can be traced through the various layers—Shaka Zulu, Mongolia under Genghis Khan, and, of course, India under Gandhi. Perpetually present also is the Western parochialism that defines, for the series, what the word ‘Civilization’ means—but this article is meant as an eulogy, so we’ll pass over that in forgiving silence. But Civilization V is that layer of ash beneath London that speaks of when Boudicca burned the city, or that is Troy VII and speaks to its mythic destruction at the hands of the Achaeans. Civilization V is when the record changed decisively: gone were the square tiles, replaced with a mesh of hexagons; where once whole armies occupied a single square, now only a single military unit could occupy a single tile. Cities became defendable objects that didn’t need a garrisoned unit to prevent enemies from waltzing in.

But these details—the units and chessboard layout—are an innovation of what was already present. Civilization V also brought with it espionage (with appropriately named spies), as well as religious and tourism mechanics that have entered the latest iteration as base gameplay after various haphazard experiments in previous games. City States were a new and tokenistic addition too, where cities whose home did not merit inclusion in the base game could now be found: Zurich, M’Banza-Kongo, and Kuala Lampur, all reductively classified as either maritime, military, commercial, or religious. Historical art objects became an important part of the game, while certain civilizations have the ability to create unique tile improvements. We have archaeologists and the introduction of historical artefacts. Civilization VI will let you play as a fascist England or a communist America once the player hits the modern era, but that system began with Civilization V.

Civilization V is that layer of ash beneath London

However, these mechanics are the canvas the game uses for its colors. The real draw of the game has always been the various civilizations available. And how many civilizations are there in Civilization V? Provided you have both expansion packs (Brave New World and Gods and Kings), 43 civilizations, from America to Zulu, are available. This includes nations as diverse as the Iroquois, the English, and the Ottomans. And, as is custom, there are civilizations that appeared for the first time in Civilization V: Poland, Assyria, the Songhai, Venice, the Shoshone, and others.

But the base 43 are merely the beginning. Civilization V came when the mod community began to come into its own, and these mods allow for the additions of, after five years, hundreds of unofficial civilizations. Of special note is the Colonialist Legacies series, which seeks to present a variety of nations and peoples created, affected by, and eliminated by the history of European Colonialism. First Nations are represented through a diverse group comprised of the Anishinaabe, Cree, Inuit, Blackfoot, Dene, Tlingit, and Wabanaki. Beyond North America, you have the Afghans led by Mirwais Hotek, Vietnam led by the Trung Sisters, Malaysia as led by Parameswara, and others. Two distinct Australian aboriginal civilizations are present: the Kimberley and the Kulin. And, of course, there is Canada, led by Lester B. Pearson.

These are merely the best, most professional examples of these community-made mods, complete with balanced abilities, appropriate in-game music, and even voice acting in the appropriate language—the Australia mod even has an animated screen for its leader, instead of, like most mods, a static image. But beyond quality, there is the fact of those unfamiliar names: how often do the names Mirwais Hotek or the Trung Sisters appear in day-to-day life? The mods, in essence, take their cue from the base game: both are constantly seeking to find some relatively unknown corner of the world and bring it to light, to show it to players and say, admiringly, “isn’t this incredible?”

In many ways, the mods go deep when the base game has to satisfy itself with going wide: Firaxis’ Civilization must lump all of Arabia or the Celts into one monolithic civilization, while the mods can parse this blanket approach apart—the Ayyubids and the Timurids or the Iceni and the Picts. But they are both animated by the same interest in taking something of that nation, that people, that empire, or that state and introducing players to their particularities. Earlier games sought to differentiate the various Civilization games by providing a different combination of starting technologies (Civilization III) or a unique unit and building (Civilization IV). But Civilization V made every civilization functionally unique by providing a different ability that reflected that culture’s distinctiveness: in the base game, the Huns burn cities twice as quickly and have an emphasis on horse archers that reflects their historical devastation of Rome. The fan community followed the developer’s lead by creating, for example, the modded Inuit civilization, who allow for the use of normally-useless tundra and snow tiles for growth, reflecting their native environment. These details are reductive, of course, implying that the uniqueness of a given culture or country can be boiled down to a unique building and a twist of the number value of certain bonuses. Yet even as the Civilization series goes on, we may see this emphasis on distinction and particularity grow—but the way in which the very nature of the gameplay reflects the specific character of your chosen civilization began with Civilization V.

So when we say goodbye to this game, we wish a fond farewell to a quizzical AI asking whether the army massing at their border is intended as an invading force. To the novelty of actual chessboard tactics, as positioning and movement order mattered in a way they never had before. But we are not just saying goodbye to this liminal game that represented a shift in the series. We are saying goodbye to the specific histories and characters, the moment when the game’s appreciation of its subject matter became more affectionately familiar. The base Civilization will always have an African empire, but it won’t always have the Songhai as led by Askia, who fears no hostile river crossing and whose mandekalu cavalry are better than most horsemen at attacking cities.

It is to the series what the Norman Conquest was to the English language

In essence, we are saying goodbye to the moment when Civilization became something that resembles other artefacts present in a civilization: language, visual art, style, fashion, whatever. Civilization I to IV were variations on a theme: the same chessboard layout, with a few changes (II and III, memorably, had a global warming mechanic) and graphical updates. Civilization V has connections to its past, but it innovates on those connections. It is to the series what the Norman Conquest was to the English language, or the invention of the stirrup to cavalry. The gap between Civilization IV and V is greater than that between V and VI—that monument to innovation deserves recognition.

Of course, the above is, partly, dramatic nostalgia. Civilization V is not actually going anywhere—it won’t disappear from anyone’s Steam account. It’s just being buried beneath the next layer. But, as with the catacombs of Paris or Rome, that underground layer speaks of a past that was once living, once its own utterly alive, breathing moment—but now serves only as a marker on the long road to the present. These catacombs may be visited by a few plucky archaeologists, but Civilization VI is now the present; Civilization V has been transformed into what came before.