Fear not, Pokémon will save the planet

Pokémon has a complex relationship with nature. It’s among the most explicit and enthusiastic depictions of natural history in kid-oriented pop culture, but environmental educators begrudge its popularity. The series gains species while our planet loses them, and that somehow feels like a bad trade—it leaves a sour taste, though it’s far from obvious that it’s a trade at all. In a sense, Pokémon’s value as an environmentalist work is something we can only see now. Climate change has touched every part of the planet, and economic development in some of the most biodiverse regions of the world is inevitable. We need ways to think about the future that acknowledge those realities, charting cultural and economic outcomes that are pragmatic but optimistic. And while it has gone largely unnoticed by its creators and its audience, Pokémon provides exactly that.

Pokémon’s origin story invokes a pastoral fantasy of preindustrial nostalgia. Creator Satoshi Tajiri spent his youth collecting insects in the rice paddies, rivers, and forests of the then-rural Machida suburb of Tokyo. Post-war economic development brought prosperity and a tech industry that would eventually provide Tajiri a successful career in game development. With that career came a chance to transmute his creek-stomping, bug-catching experiences into mass entertainment. But economic development also meant that the forests, rivers, and rice paddies themselves were logged, drained, and paved over. Tajiri’s digital simulacrum, with its 151 carefully cataloged Pokémon, replaced the uncounted thousands of real insect species dwelling in Machida for hundreds of millions of years.

Pokémon’s value as an environmentalist work is something we can only see now

This is an iteration of the most familiar trope of 20th century environmentalism: greedy, short-sighted corporations permanently destroying ecosystems with no regard for their intangible worth. It’s Fern Gully (1992), it’s Avatar (2009), it’s most particularly the neglected Studio Ghibli classic Pom Poko (1994). But while its origin myth places Pokémon in a familiar discourse about nature, that narrative is oddly absent from the games themselves. Rather than having Ash fight developers to protect Pokémon habitats, conflict comes from defanged terrorism espousing marginalized ideologies. The environment is entirely static and unthreatened, as if it has reached an equilibrium and come to terms with the economy.

For a landscape full of wild nature to feel safe alongside a technologically-advanced, ostensibly capitalist society is a somewhat unfamiliar juxtaposition for us. It feels like a fantasy, a wish fulfillment in which Tajiri keeps the prosperity and technological tools of his adult life while returning to the unspoiled countryside of his childhood. As if the games were pretending that technological capitalism wasn’t inherently at odds with wild nature, shielding their young audience from the disenchanting truth. While Pokémon’s writing is often charming, its approach to its themes is generally shallow, so this have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too fantasy of nature and technology in harmony is generally written off as a necessary premise that would fall apart under closer questioning. That’s unfortunate, because questioning that premise reveals that Pokémon offers a compelling and progressive vision of the future of nature in post-industrial economies.

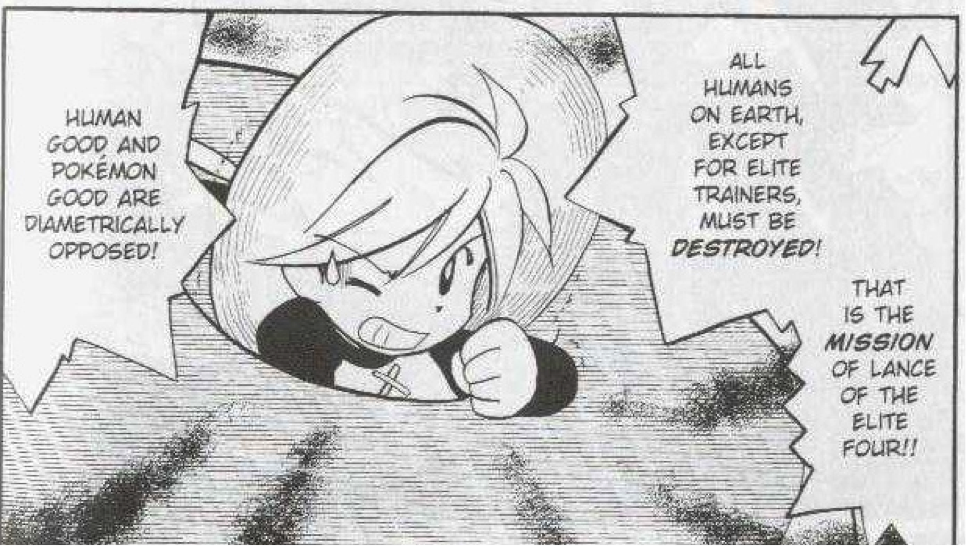

Pokémon’s worldbuilding is opportunistic, rarely passing up the chance to reference a real-world animal trope or make a bad pun, even when doing so undermines the coherence of the culture and ecology of Kanto, Johto, and their successors. The rhetoric of the terrorist Teams often hinges on environmentalist philosophy, but inevitably feels like a poorly understood misapplication of real-world ideologies. The Pokémon Yellow manga arc poses the Elite Four as proponents of Intentional Human Extinction who want to give the world back to the Pokémon. Pokémon Black/White’s (2010) Team Plasma has comparable ideas, aspiring to release Pokémon from their servitude to trainers. Both seem to make reference to radical environmental groups like the Animal Liberation Front, but in the context of Pokémon they come off as utterly foreign ideas. The narratives of systemic violence and oppression they refer to just don’t apply within the Pokéverse.

Yellow Chapter, Pokémon Adventures Manga

Aside from its often-incoherent stories, however, everything about the Pokémon world reflects a coherent environmental philosophy. It acknowledges that humans—even industrial humans—are part of nature. In the tradition of environmental historian Bill Cronon’s work on the Wilderness Myth, it understands that emphasizing “virgin” wilderness is a counterproductive and misleading fixation, erasing histories rich in positive human interactions with nature. The Wilderness Myth is largely a Western concept, a product of colonial interactions with landscapes depopulated by disease and genocide. Landscapes in Japan have been densely inhabited and thoroughly exploited for many centuries. Tajiri’s Machida stomping grounds were carefully managed rice paddies and forest borders exploited for wood, fertilizer, and fuel. This border landscape, called Satoyama, is a touchstone of the magic of nature in Japan, embodied by Studio Ghibli’s forest spirit, Totoro. It also provides crucial habitat for animals and insects, many of which benefit rice farmers by controlling pests, pollinating crops, and mitigating pollution. Satoyama is an example of a pattern of ecological coexistence called reconciliation ecology. The ecologist who developed the concept, Michael Rosenzweig, defines it as “the science of inventing, establishing, and maintaining new habitats to conserve species diversity in places where people live, work, or play.”

Rosenzweig points out that even after they are paved and developed, suburbs like Machida aren’t ecologically barren. With some thought and attention, those resources can be shaped to support greater biodiversity. In practice, Rosenzweig’s examples are found largely in agricultural systems like Satoyama and in historical happenstance, like peregrine falcons nesting on concrete skyscrapers in place of limestone cliff faces. But dozens of intentional techniques exist, from green roofs and native plant landscaping to nest boxes for birds and bats. And with thousands of species already endangered and human land use expanding exponentially, it is increasingly clear that conservation biology can no longer turn down these modest opportunities to improve habitat. The entire world is reaching densities of land use that Japan hit long ago, and it must adapt strategies like Satoyama to achieve a comparable sort of sustainability.

Satoyama in My Neighbor Totoro

Alongside preserving existing habitat and incorporating reconciliation techniques within human land uses, enacting a regional-scale conservation plan usually requires converting some agricultural and industrial land back to native habitat. This process, known as ecological restoration, involves planting seeds of plants native to the site before it was developed, as well as reestablishing populations of animals no longer found there. Unfortunately, restoration is currently only possible for surviving species, though some ambitious—and perhaps radical—conservationists point to developments in cloning technology and suggest that extinct species will be eligible for biotechnological resuscitation within a few decades.

At the moment, restoration and reconciliation practices are scattered and poorly supported, limited to places where conservation-minded people live and vote. They are constrained by cultural resistance and economic marginalization. Both factors are resolved completely by Pokémon’s premise, and the consequences are written on the landscape.

The culture and economy of the Pokéverse are oriented almost entirely around Pokémon, providing a near-universal investment in conservation. It’s the realization of the dream of ecotourism—a sustainable market based on the appreciation of nature rather than its exploitation. The economy is affluent and post-industrial. Nearly every character either works a Pokémon-related service job or spends their free time battling and practicing a hobby—often related to outdoor recreation, like roller-skating, swimming, or hiking. In Pokémon X/Y (2013), the only land uses that aren’t inhabited by Pokémon are the Poké Ball factory and the solar power plant, both pillars of the Pokémon economy seen in action everywhere else. Even in the most “natural” areas, every space is thoroughly netted with signs and paths. Infrastructure is provided to cross rough terrain. You’re never far from a Pokécenter, and there are usually dozens of tourists around. It’s not an untouched wilderness, but a working landscape.

It’s the realization of the dream of ecotourism

The whole environment, including roads, towns, and natural areas, appears integrated into a publicly managed regional plan. Each region includes distinct habitat types—beach, cave, forest, ice cave, haunted house, abandoned power plant—suggesting an intentional effort to support a high diversity of Pokémon types, attracting tourists and supplying the Pokémon whose capture drives the economy. And while a few legendary Pokémon seem to need large, undisturbed areas, the rest of them appear habituated to constant human presence and relatively small patches.

The historical trajectory of this landscape mosaic is never discussed. Whatever extinction, evolution, and adjustment took place to reach the present distribution of Pokémon has apparently already taken place. It is possible, though perhaps unlikely, that all of the natural areas we see have never been substantially altered by humans. On the other hand, with fossil revivification, the technology is there to achieve the Jurassic Park dreams of the most enthusiastic and reckless rewilding advocates. And captive breeding of Pokémon is a reliable and commercialized technology, so small endangered populations could easily have been reared back to target abundance. Ecological restoration would be comparatively cheap and easy in the Pokéverse, and the demand for places to catch wild Pokémon clearly make it worthwhile. That said, without any sense of the history or management of these areas, it’s unclear whether their current distributions reflect historical ecology. It’s possible that natural areas are stocked with economically-desired Pokémon the way many local governments regularly introduce non-native sports fish into lakes and rivers.

The mosaic of roads and habitat patches in the games matches the distribution of Pokémon neatly, but this artificial stability belies the tendency of real wildlife to wander between patches. Roads are lushly supplied with grassy, no-mow zones, supporting more common and agrarian Pokémon. In theory, this should allow roads to act as corridors, safe routes that allow Pokémon to move between other habitat types. Such movement is an important technique to protect species from extinction, allowing patches with depleted populations to be recolonized by migrants from more robust populations. In practice, Pokémon never move beyond the boundaries set for them by the developers. But at least on paper, regions are designed to accommodate dynamic, interconnected ecosystems based on modern landscape ecology.

Yellow Chapter, Pokémon Adventures Manga

Cities are the weak link in Pokémon’s reconciliation ecology credentials. With a few cordoned-off exceptions like sewers, the games use cities as safe hubzones, completely free of wild Pokémon encounters. This sort of missed opportunity suggests that Pokémon’s ecological philosophy may be inadvertent. On the other hand, Pokédex lore and some scenarios from the manga and anime show that many wild Pokémon exist in cities as well—particularly, those Pokémon that seem to exist only through the creative tension between humans and nature. The Pokéverse’s post-industrial history is written into the bodies of these Pokémon. Some electric types, like Pikachu, might invite comparisons to evolved creatures like electric eels, but many of their designs are explicitly industrial, and they often consume grid-generated electricity. Koffing, Grimer, and Trubbish are living accretions of pollution and trash. Like pigeons, rats, and cockroaches, all of these Pokémon have evidently been transformed by close relationships with urban economies, even if their progenitors may have existed before industrialization.

Pokémon GO has thoroughly rectified that urban oversight. The game attempts a rough habitat mapping, urban Pokémon in cities, bug types in parks and forests, and water types near lakes and rivers. As a result, most players have been flooded with uber-common synanthropic Pokémon like Rattata and Pidgey, devaluing them as “trash” just as familiarity has bred contempt for real urban animals. On the other hand, as players seek out Pokémon in urban environments, their encounters with squirrels, pigeons, and rats will perhaps make Pokémon’s parallels with biodiversity coexistence easier to frame. Pokémon GO lacks the utopian world building of the games, but it will certainly color how players experience the upcoming Pokémon Sun/Moon.

Pokémon GO has thoroughly rectified that urban oversight

While natural areas are thoroughly enmeshed in the human economy, they aren’t necessarily safe. Wild areas are designed to be places where trainers interact with wild Pokémon in battles with strict norms of fair sportsmanship. Trainers rely on domesticated Pokémon to protect them from wild creatures, which apparently attack humans passing through their territory. This relationship acts out in microcosm a tenet of human history often neglected by simplistic “man versus wild” stories (regardless of whether man is depicted as conqueror or desolator): humans have survived and thrived in a hostile world only by cultivating positive relationships with animals, plants, and microbes. Pokémon trainers, with their diverse, mutually reliant teams, are among the few figures in the fantasy genre that give proper credit to those relationships.

Pokémon’s capturing mechanic references our boundary between wild and domestic animals, but it shifts that line from the species to the individual level. Domesticating a Pokémon involves the instant formation of a psychological bond, not a gradual genetic change. By making every Pokémon eligible for partnership with humans, every other category we apply to animals is blurred as well. A few Pokémon, like Machop, are used as beasts of burden, but they are also fighters and companions for the laborers that use them. Pikachu appears as a restaurant pest in the manga—they are mice, after all—but also a source of backup electricity in the anime. Misty has a phobia of bug-type Pokémon in particular, but she doesn’t think it’s appropriate to kill them. No one ever mocks someone for catching and fighting with a particular Pokémon. Pest, vermin, predator—categories that still keep people from embracing rats, possums, or wolves as part of our ethical responsibility—have been transcended.

A Machoke construction worker, Diamond & Pearl Episode 57

Every few years when a new Pokémon title is released, Game Freak’s artists give the kawaii-culture treatment to another hundred animals, plants, and abstract ideas. That’s the logic of capitalism at work, but it resonates with an increasingly ecumenical relationship with nature. Pokémon makes no distinction between cute pets like puppies and kittens and wild animals. Everything is available for consumption and capable of productive relationships with people, given the right approach from the trainer. This is the nature fantasy of an urbanized population, people who interact with nature primarily by watching baby animal videos. Many such videos are from animal rescue shelters that support themselves by marketing the cuteness of their unique and exotic wildlife—see Vice’s The Cute Show, much of Animal Planet’s programming, or the incredible number of possum rescue pages on Facebook. Our consumptive horizon has widened, and our ethical and economic horizons are gradually following. After all, the slogan is “Gotta catch ‘em all”—no outs are provided for gross, standoffish, or dangerous Pokémon.

Pokémon is a strange beast. In a sense, it seems to have deliberately ignored the negative implications of economic development in a way that feels almost disloyal to its origins. On the other hand, its rhetoric frequently invokes a dramatically exploitative history between humans and nature, even though that relationship otherwise feels anachronistic in Pokémon’s idealistic future.

The series is unapologetically utopian, erasing or belittling many of the most consternating philosophical and material issues standing between us and its endpoint. But its philosophy completely shatters the Wilderness Myth, presenting a culture that manages to be ecologically inclusive and ethically egalitarian despite retaining the responsibilities of a technologically-bestowed power dynamic between humans and nature.

Rosenzweig sees “reconciliation ecology as the great environmental educator. The environments it creates will teach us once again how to take pleasure from Nature. The species we live with will resensitize us to her delights and addict us to her bounty.”

Environmental educators treat digital nature as a cheap substitute, claiming that we need to “get kids outside” to experience “real” nature instead of playing videogames. That’s an important effort. But it might also be true that Pokémon’s vision of a post-industrial culture intimate with a wealth of wild creatures could serve Rosenzweig’s purpose as well. The series provides a plausible blueprint for a world that addresses many of the environmental catastrophes we have to deal with in the next century. Pokémon deserves credit for advancing that vision, however inconsistently and accidentally, introducing intentional coexistence with all wildlife to millions of people not as a nostalgic fantasy, but as a compelling vision of the future.