Some weeks ago, a piece of news shook my world. It wasn’t the primary election results, nor was it Muhammad “The Greatest” Ali’s passing—even though that one was really, really sad. Nope, it was a parrot. CBS reported on June 10th that Bud, an African grey parrot who kept repeating the phrase ‘don’t fucking shoot’ after his owner was murdered, could become a witness in trial.

We all read bizarre stories online every day, but this one instantly reminded me of a Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney (2001) case, where a parrot testifies in court—and there’s more to the parallel too, as the game is set in 2016. Therefore, we can now bafflingly state that Ace Attorney accurately predicted a rather unimportant fact in our everyday lives.

Jokes aside, this unusual coincidence can remind us of our fascination for clairvoyance. Characters endowed with foresight have been part of Western culture since classical antiquity. In Aeschylus’s tragedy play Agamennon, Cassandra—princess of Troy and Helenus’s twin sister—is given the power of prophecy by Apollo in an attempt at seduction. When Cassandra refuses to lay with the Olympian, Apollo puts a curse on her: no one shall ever believe in her visions. She’s deemed mad by everyone after she foresees the fall of Troy by the hand of the Greeks.

Many centuries have passed since Aeschylus. Yet, mankind has kept itself enthralled by the future and the power of predicting it throughout the years. We’ve even reached a time when authors, film directors, and game makers assume the prophet’s role. But, unlike Cassandra, they don’t have to worry about being credible since many of their works rely on our suspension of disbelief to properly enjoy them.

mankind has kept itself enthralled by the future

What fuels the imagination of these modern creators? What gives them the idea that humanity will face the sovereignty of dystopian dictatorships or gargantuan corporations? I believe the answer lies in their very own present: technological advancements, social questionings, the disquietitude of society. We are constantly surrounded by these things and our perception of them can inspire creation.

Since it’s now been mentioned, it’s worth considering that dystopia has been quite a popular theme in various media since the late 19th century. From H.G. Wells’s short story A Story of the Days to Come (1897) and Fritz Lang’s acclaimed film Metropolis (1927), to the avalanche of post-apocalyptic videogames that surfaced lately like The Division, envisioning an ominous future—or even a horrendous, parallel present like The Last of Us (2013) did—has created a whole stream of media that keeps captivating its public.

George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four lies among the most celebrated works of the dystopian genre. Published in 1949, the novel is set in a world composed of gigantic, multi-continental and dictatorial countries engaged in war. Its plot focuses on the political system of Oceania, named English Socialism and demonstrated by the trajectory of protagonist Winston Smith within it. Orwell’s fictional state is driven by a nationalist force which bows to the figure of Big Brother, its ruler, who might not even exist. Also, the Oceanian government frequently resorts to historical revisionism, brainwashing, and persecution to extirpate any individualistic thoughts within its territory.

Nineteen Eighty-Four was inspired by the author’s comprehension of his own time. World War II was coming to an end during the novel’s incubation and subsequent materialization. Like many, Orwell was trapped in a boiling cauldron. An exposition of his take on his contemporaneity is made in a letter addressed to a certain Noel Willmett, who had asked him if totalitarianism would really be a tendency after the war ended. The content is revealing:

“I must say I believe, or fear, that taking the world as a whole these things are on the increase. Hitler, no doubt, will soon disappear, but only at the expense of strengthening (a) Stalin, (b) the Anglo-American millionaires and (c) all sorts of petty fuhrers of the type of de Gaulle. (…) If the sort of world that I am afraid of arrives, a world of two or three great superstates which are unable to conquer one another, two and two could become five if the fuhrer wished it. That, so far as I can see, is the direction in which we are actually moving, though, of course, the process is reversible.”

We could credit the author for foreseeing a polarized world order which was fundamental for the Cold War to exist. Also, the lack of transparency and abuse of censorship in the USSR resemble Oceania’s modus operandi. For example, Leonid Brezhnev’s assassination attempt in 1969 was followed by a news blackout.

imminent atomic end

The year of 1984, though, didn’t look anything like Orwell’s prediction. The Soviet Union was facing its decay in the 1980s—Brezhnev’s ruling was named the “Era of Stagnation” due to its continued failing social and economical policies, and the Gorbachev period was determinative for the fall of the USSR. In fact, Gorbachev’s glasnost, which made government decisions more transparent and gave people more freedom of speech, entirely contradicts Nineteen Eighty-Four’s envisioning.

It is interesting to note that a piece of Orwell’s correspondency shows that these dystopian visions were seen as legitimate concerns during the 1940s and not solely praised by its literary content. In a letter, Aldous Huxley compares his predictions on Brave New World (1932) to Orwell’s and claims his hedonistic and alienated society is more likely to become real.

Aside from iron fist rulers, another considerable effect from World War II’s aftermath was the fear of a nuclear holocaust. Amazing pieces like Akira Kurosawa’s I Live in Fear (1955) have depicted this postwar concern as a matter of its own present, but atomic fallout-ridden worlds were a fascinating and futuristic setting for many works.

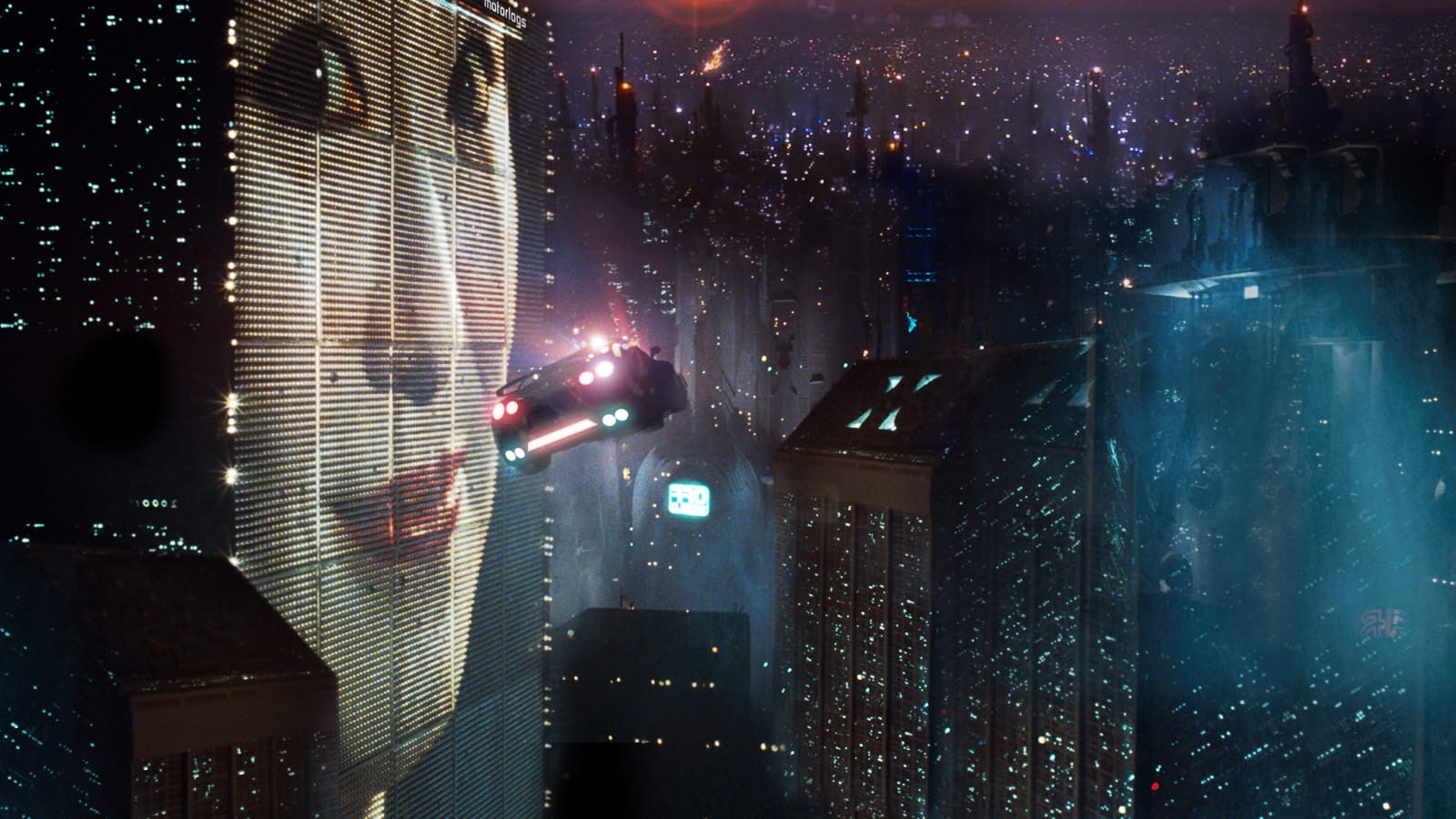

Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), which was adapted to the big screen in Ridley Scott’s cyberpunk opus Blade Runner (1982), foresees a mass evacuation from Earth to space colonies due to the results of World War Terminus, which polluted the planet with radioactive dust. Written at the height of the Cold War, the book is originally set in the year of 1992. For literary reasons, presumably, later editions postpone its apocalyptic setting to 2021. Still, it is not incoherent to believe that our justified fear of nuclear weapons will prevent the world’s demise until then.

Interestingly enough, it seems that society feared an imminent atomic end to itself until the late 1980s. Interplay’s Wasteland (1988), which inspired the studio’s Fallout series, predicted that a nuclear doomsday would take place 10 years after the game’s release. Its plot, though, is set in 2097.

a horrendous, parallel present

On a lighter note, some early 1990s videogames showed concern about ecological issues. Environmental damage had been a central matter for years due to events like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) publication, and conferences held in cities like Tbilisi in 1977 and Rio de Janeiro in 1992.

An example of the sort is Aerobiz Supersonic (1993). An aircraft business simulator, Supersonic let the player manage an airline in four different scenarios comprised in 20 years each: 1955 to 1975, 1970 to 1990, 1985 to 2005, and 2000 to 2020. During the years prior to the title’s release, the game presents real-life events like the Olympics and the rise of Fidel Castro, which change geopolitical situation, economical balance and, therefore, flight demand to some destinations.

In the last playable period, the game tries to foresee its close future by creating fictional events. During these years, the player is constantly asked for money by countries to fund research on alternative, less pollutant fuels for airplanes. Even though public awareness was drawn by documentaries like An Inconvenient Truth (2006), climate change has lost its space in media during the current decade to be replaced by social and economical issues—a reflection of the 2008 crisis.

Aerobiz Supersonic also tried its hand on the future of commercial aircraft by claiming that supersonic travel would lead the market. To this date, only two civil supersonic airplanes were used in commercial flights: the Concorde and the Tupolev Tu-144. Both were retired.

Whether they depict a dystopian setting or try to keep their feet on the ground, predictions of the future in media remotely work like fashion shows or concept car designs: they might not reflect the final product, but they try to point out tendencies—truthfully or not. We might not be tormented like Cassandra, but it seems that we’ll always try our hand at clairvoyance, even though we’re constantly flawed by our perception of the present.

it seems that we’ll always try our hand at clairvoyance

However, some theorists are taking this urge to foresee to unexpected paths. In his 2001 article, Are You Living in a Computer Simulation?, Nick Bostrom defends the notion that we might be living in a computer-simulated environment, created by a highly-advanced civilization. He argues that if we can envision a future when technology permits mankind to faithfully reproduce a society with a highly-developed, conscious AI, then we could already be living in this simulation itself. Obviously, this is but a short summary of Bostrom’s argument, but I recommend reading his full article, especially as his work was recently defended by entrepreneur Elon Musk during this year’s Code Conference.

Right now, our predictions of the future are concerned with the integrity of our own reality. It’s not surprising when you consider the rise of videogames and virtual reality in recent decades. You only need to look at a group of adamant Pokémon Go players trawling your local park to realize how quickly we humans are to abandon our reality for another. And so we can see how our tendency to predict the future, as useless and fearmongering as it can be, is able to bring the public consciousness into a position where it may at least consider the philosophical questions that are deeply connected to our current form of existence.