The fierce independence of the No Man’s Sky soundtrack

Samizdat—literally “I self publish” in its native Russian—is a term that buzzes with connective meaning. First used by the poet Nikolai Glazkov, it describes the banned political essays, literature, music, and poetry that were circulated by makeshift independent presses in the Eastern Bloc. A response to the extreme censorship of foreign and dissident works during the 1950s and 60s, samizdat publications were emblematic of a fierce spirit of independence, produced through unlikely means. Carbon-copied verse, hand-typed novels, even bone records cut from old X-rays, were distributed by hand, passed from trusted friend to trusted friend, to be read or listened to in the deepest parts of the night, under a flickering candle.

So when the word comes up in my conversation with designer Caspar Newbolt about his work on 65daysofstatic’s soundtrack for No Man’s Sky my ears prick up. Newbolt, director of Version Industries, is responsible for the idiosyncratic art that adorns 65daysofstatic’s new release, but to call him a cover designer would be a great disservice. He is one of the collaborators that make up 65’s wider creative circle, and his work with them has been a decade-long relationship of thoughtful design. “I was talking with the band a few days ago,” Newbolt explains, “and one of them used a word that I think really encapsulated everything that we’d done here together. That word was samizdat.”

music for an infinite universe

Newbolt is a hard man to pin down. When I ask him about the sigils that mark the cover of the album design, or the fractured main image he dodges the question: “It’s always my interest to not explain a great deal,” he says, before politely adding “so that the work can speak for itself as much as possible.” His reasoning is sound: “we’ve had a lot of questions already about what it all means, and like a good record or film I think there’s a greater value in people forming their own interpretations.” But he does, after a little pushing, give me a thread to follow, that word— samizdat. And it’s a good thread, one that sets my mind running when I look at the art that surrounds the album.

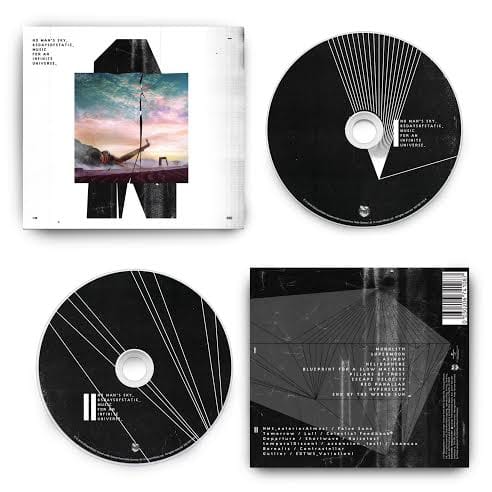

It’s there in the cover’s heavy wear; a texture that might have flowered from a photocopier or scanner—digital and analog decay creeping in at the edges. Then there’s the central painting, by collaborator John DeLucca, which is split like a photographic plate, or perhaps just cut with a photoshop marquee, the clean breaks betraying neither one origin nor the other. A monolith of sorts sits behind, peppered with more copier noise, its sharp angles part alien sigil, part choppy-scissor cut-out. In short, it looks like an elegant bootleg, an artifact of digital and practical processes of distribution, rich with error and obscurity. This theme is carried across its iterations, in the branching diagrams that adorn the CD, and the four chopped and blocked landscapes that lie inside the chunky four LP boxset.

For Newbolt, this aggressive treatment emerged from navigating the disparate styles that defined both No Man’s Sky’s saturated dreamscapes and 65daysofstatic’s black-market chic: “No Man’s Sky, the game, is clearly a tremendously well executed project with a strong, pre-established aesthetic.” He explains that “the game’s soundtrack was similarly composed and structured in the way few have ever been before. Faced with these facts I had to conceive a visual that somehow spoke to these different concerns, and that helped you see and hear the music through 65’s own eyes and ears.” The result was the obscure, ambiguous design you see now, one that splits from the game’s clean lines by muddying them with layers of noise. For Newbolt, this was not just about style, but legacy. “What you see in the artwork is the No Man’s Sky aesthetic filtered through 10 years of knowing a band who, like the game’s procedural score, never stop trying to find new ways to express themselves.”

But what of the soundtrack itself, how does it navigate the disparate styles and demands of No Man’s Sky and 65daysofstatic’s differing identities? The first track, “Monolith” is a good indication. Drifting in on building layers of guitar drones before locking into a clipped drum beat, it feels instantly recognizable as part of 65’s own style. Yet, before long, that conventional intro decays into a urgent synth line, which leads us willingly into the face of some glorious, reverb-rich fuzz. Everything is gathered, layered, stretched, crushed, and by the time groaning errors light up the dark drumbeats like glitched suns, it’s hard to feel you are listening to the same track. It’s decay at high velocity, built on repeating structures that fall and build in a linear form designed to transition you from one state to another. This journey from signal to noise and back again is what animates the album.

Each of the other tracks in this collection possess their own territory on this spectrum. “Supermoon” (perhaps the most recognizable, having been used in No Man’s Sky’s trailers) sits at one end; the 65 signature drum-beat a guideline through lilting layers of bright-eyed piano and spaced-out choirs. It feels like comfortable place for 65, a building set of rifts that push for euphoric release, sprinkled with those blippy synths they handle so well. “Asimov” seems like it might occupy the same space until a mid-song lull lays the ground for the closest the album gets to an almighty drop, one that through hammer-blow drumbeats and some rare unadorned strumming feels like the most post-rock this band will ever get.

“Heliosphere” and the perfectly named “Blueprint for a Slow Machine” reroute the path, wiring us directly into a Proteus-like world of twinkling digital flora and fauna, albeit with an ever-present bedrock of dark drones. This is true science-fiction territory, with “Slow Machine” even launching itself as a Vangelis tribute act before suddenly churning into an interlocking structure of drum machines and dysfunctional electronica. Yet both refuse to reach the end of their five minutes without those crowd pleasing guitar riffs and beat-perfect drum rhythms sneaking in and brashly taking over the show. As though to provide a counter argument to that point, the following track, “Pillars of Frost,” marks our arrival the other end of that signal to noise spectrum: a washed out and frankly beautiful wall of distortion. Here is the split plate, the sharp edges, the flowering grain across a distant landscape. The empty and yet full air of another earth.

Having stranded us on that shore of noise, the album senses that it is time to bring us home again. The piano returns in “Escape Velocity,” laying down a scale of footfalls to guide us to whatever craft will bear us back. It is built of the familiar; “Red Parallax,” the shimmering new; “Hypersleep,” and the ornate mechanisms present in the uplifting form of “End of the World Sun”. From this far end, it is easy to see it as a journey in both one and many parts, its total structure possessing a distinct shape that is mirrored and distorted in each of its pieces. 65’s strength has always been in their synchonizationation of the analog and digital, shaping seemingly contrasting sounds into coherent landscapes. As an album, No Man’s Sky: Music for an Infinite Universe feels like a powerful actualization of this process.

And we should call it by its full name, because 65 deserves recognition for producing an album with its own independent spirit rather than just a soundtrack. Perhaps it is because they have pushed the ambient, procedural soundscapes that will accompany much of the game onto a second Soundscapes disk, allowing their 10 tracks the breathing room they need. This second disk, a set of glittering backdrops that wander easily across the tones of the album, dragging out moments to eternities, makes for a strong companion. There is something pleasing about the rudimentary parts of the track titles, such as “NMS_exteriorAtmos1” or “ascenion_test1,” that point not just to the exploratory processes used in their making, but also that bootleg aesthetic that feels central to the album and 65. The grouping of the tracks, their aimlessness and impregnability, play beautifully into the sense that this second disk is a mysterious artifact, the kind you might find on a dusty CD-R, etched with marker pen letters in some impregnable alien language.

This is perhaps the clear point of unity between No Man’s Sky and this album: Not only do they share concerns and ideas, but the same sense mystery and obscurity as well as an obsession with the artifacts of a digital world. Rather than simply mirror each other, or form an obvious hierarchy, this allows these two distinct works to sit side by side.

Listening to the album, and perhaps guided by its layers of building fuzz, I couldn’t help but think of the band HEALTH and their work for Max Payne 3 (2012). One of the all time great soundtracks of any game; inventive, surprising, and beautifully produced (just listen to the track “Shells” if you don’t believe me), I was surprised to find out that it marked a dark period for the band. “When the game came out, most of our fans were just like, ‘When are you guys gonna do anything?’”commented bassist John Famiglietti in an interview with Pitchfork, adding “our fans have been aggressively pissed at us for the last three or four years.” Perhaps this was because, unlike 65, HEALTH’s soundtrack was released as a wandering set of mismatched tracks, gathered with the Emicida track from the game, and plastered with the game’s cover art and an “OFFICIAL SOUNDTRACK” tagline. In short, they gave up their independence, or had it taken from them.

Speaking to Newbolt it’s clear that, at least in part, we have No Man’s Sky developer Hello Games to thank for 65 avoiding this unproductive approach. “Hello Games are big fans of 65daysofstatic.” he explains, “in understanding 65 the way they do, they very much wanted them to approach the soundtrack the way they’d approach any of their own albums.” But it is also clear that the album’s independence didn’t come without a struggle. And in a project as big and with as much potential as No Man’s Sky, it’s not surprising to hear that there were some battles along the way. Newbolt sees that conflict as all part of what the band does: “As a partnership we’ve come to learn over time that our best work doesn’t come without a good fight. We simply have to keep pushing each other to articulate what we really want to say, whether that is to each other or to others.” Who those others were Newbolt doesn’t make clear, but he makes it clear that the focus of both the band and himself have been and always will be firmly on what they want to say, not on how others want them to say it: “Naturally this often comes in spite of what the expectation from outside parties might be, and in this case the expectation was of course very different from any of our previous projects.”

from signal to noise and back again

In a way, it seems that 65, and Newbolt, weathered that particular storm through a sense of aesthetic unity. “I’ve known and worked with the band for 10 years now, and twice have toured with them in different parts of the world,” Newbolt says. “In this time we’ve come to understand and trust each other.” This trust is what allowed Newbolt to produce such distinct work for the album’s cover. “I was given a copy of this soundtrack early on and I knew, as ever, that being responsible for creating visuals for this record would push me to do some of the best work I’d ever done.” In a sense, this idea of trust, but also of collaboration is central to the successes of No Man’s Sky: Music for an Infinite Universe as a total work. The trust of Hello Games instigated the idea of an album to sit alongside the game, not in service of it, and the clear trust between the band members and its collaborators allowed them to follow through on this idea.

That samizdat slogan, “I self publish,” also implies the idea that “I self define.”. With that in mind, we can see how 65daysofstatic’s insistence on their artistic independence, their fierce sense of individuality in their music and their self-knowledge as a creative group of collaborators have led to the creation of a defining work. No matter the success or failures of No Man’s Sky, the band and their collaborators can feel safe in their own independence, and in their desire to pursue their own intentions. It is the alignment of ideas that makes for strong collaboration, not the rule of one single, all-powerful idea. In that way, projects like this become a game of listening, not just to others, but to the directions of the work itself. As Newbolt puts it: “We’re never really out of touch, but it takes a moment to tune back into each other’s frequencies.” This truth suggests that among all that noise, there is signal after all.