Final Fantasy X / X-2 enshrines the series’ awkward teenage years

Videogames, we know, are still growing up. They are just now finding their place in society, they often pretend to be more mature than they genuinely are, and they have a lot more potential than most people give them credit for. Games as a medium are replete with adolescent fantasies draped in the trappings of adulthood: machismo, hyperviolence, profanity, tasteless nudity. You can’t browse a catalog of games without stumbling over a dozen such titles: Grand Theft Auto, Gears of War, Saints Row. These games offer a smorgasbord of immature delights for teenagers who’d like to pretend to be adults or for adults who’d like to indulge their teenage impulses.

So it is refreshing, in returning to Final Fantasy X and its mostly goofy follow-up, to find stories which are actually about teenagers, which tackle adolescent themes without any pretension of being “adult.” These are stories about finding one’s place in an unfamiliar world, trying to live up to the legacy left by one’s parents, coming to terms with loss, and trying to negotiate when to put one’s own selfish needs above those of the people that surround you. They’re stories about finding love for the first time, and fighting to keep it, and figuring out what to do when that seems impossible. They are stories about being a teenager, and for all the adolescent fantasies that populate the medium, stories like these are seldom treated with any kind of sincerity and depth of character. Final Fantasy X is so genuine and full of heart that it stands out even thirteen years after its release. Final Fantasy X-2, well, it’s perhaps a little less sincere–but it’s so mechanically engaging that it’s likely to keep you enthralled while you wait for the moments of sincerity and heart to reveal themselves to you.

These games offer you two parallel but decidedly different trips through the world of Spira, a tropical paradise inspired by the architecture and climate of Southeast Asia. The first journey tells the story of the impulsive, somewhat spoiled Blitzball player Tidus, and it is an exercise in negotiating the contrast between Spira’s idyllic locales and the shadow of imminent death that hangs over them thanks to the colossal avatar of destruction known as Sin. The second journey, which focuses on the demure, polite ex-Summoner Yuna, shows you Spira through a much different lens: with the constant threat of Sin removed, what do the world and its inhabitants do with their newfound freedom?

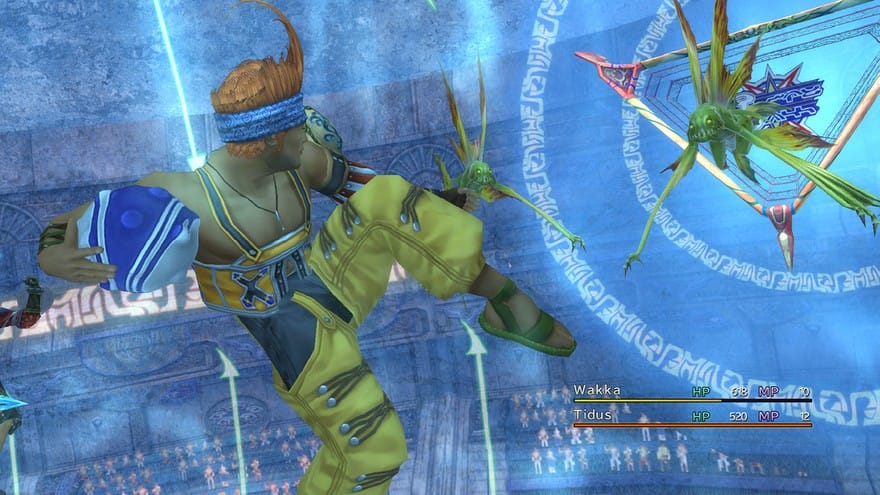

This two-pack, then, makes sense, not just as a completionist collection but because games complement each other. Besides having wildly different tones, they’re also structural inverses: By virtue of being a pilgrimage, FFX’s story and navigation are mostly linear (though perhaps not quite as extremely linear as Final Fantasy XIII). FFX-2, on the other hand, allows you access to every point on the map from its very first chapter, and its episodic nature means that a considerable bulk of its content is sidequests. The battle systems in the two games are also opposed: FFX has true turn-based battles, which encourage thoughtful consideration of one’s attacks and swapping in party members who can best deal with the enemy at hand. FFX-2, by contrast, has what is perhaps the most frenetic battle system in the entire franchise, with allies and enemies often acting nearly simultaneously.

Both types of combat remain compelling, even today. But going back and playing these games so long after their original releases is a little bit like getting an honest look at yourself when you were a teenager: There’s much that seemed totally normal and understandable to you at the time that now appears, well, less so. Though the typically handsome cast of characters has received a set of HD facelifts, they still jerk around like puppets, practicing pre-determined choreography that only sometimes conveys what it means to. It’s not helped by the voice acting, which in the English language version varies wildly in quality, from emotive to cringeworthy. And make no mistake: there are a lot of cutscenes in these games. The ratio of watching-versus-playing is pretty high here, and FFX doesn’t give you the option to skip its story sequences. (FFX-2 affords you this courtesy, at least—but only if you don’t care about your completion percentage.)

While Final Fantasy X-2 smooths over some of the awkwardness of presentation, its real weaknesses are more deeply entrenched. Although it’s superb to have an entirely female playable cast, some of the skimpy outfits and magical-girl-style costume changes wink too hard at you, elbow you in the ribs a little too frequently. Though FFX has its fair share of exposed skin (black mage Lulu’s outfit, in particular, causes some heavy sighs), FFX-2 takes its Charlie’s Angels premise as an excuse to go wholly overboard with the idea. You can fiddle with the settings in the menu to shorten or remove the costume change sequences, but there’s no option to give Rikku some performance fleece when you’re visiting snowy Mt. Gagazet.

And the reasons why you’ll be sending these women so ill-dressed for adventure across the globe can be questionable. A number of missions will see you performing such exciting tasks as handing out balloons to passers-by, attempting to find mating pairs for monkeys, and advertising a theme-park company. You aren’t obligated to engage with all of this stuff, but that doesn’t stop it from feeling like filler. You will be obliged to engage with recurring comic villain Leblanc, who is almost certainly more aggravating than you can imagine, and Rikku’s brother, who is two steps away from being a Borderlands Psycho.

If you can get past all of these artifacts of 2001-era game design, however, there’s an enormous amount of virtue within both games. Tidus’s story, from his origins in futuristic Zanarkand through Yuna’s pilgrimage to defeat Sin, offers perhaps the most dramatic character development of any protagonist in the series. For all the awkward cutscenes and stilted voice acting, the game’s final act is surprisingly moving. The scenes in Final Fantasy X-2 in which Yuna is forced to confront the specters of the past, both her own and Spira’s, are potent. The parts of the narrative that aren’t graceful don’t stop Spira from being a beautiful place to exist in for a few dozen hours.

Or, at this point, a lot more than that: this is two 40-50 hour games, each of which has received new optional bosses, summons, and job classes; a hefty “bonus dungeon” for FFX-2 that plays much differently than the main game; a couple 30-minute story sequences (one of which bridges the gap between the two games, one of which acts an epilogue to the whole journey). While not all of these additions provide substance, that central experience is lovingly presented. Like any thirteen-year-old, its awkwardness sometimes obscures its sincerity, and it can be disdainful of your time. But like every thirteen-year-old, it’s got powerful, worthwhile stories to tell, if you have the patience to sit down and listen.