Firewatch and the great American landscape

Steven Poole put it beautifully in his book Trigger Happy (2000): “the jewel in the crown of what videogames can offer is the aesthetic emotion of wonder… such videogames at their best build awe-inspiring spaces from immaterial light. They are cathedrals of fire.”

Cathedrals of fire. Sit on that for a moment.

I’m at my computer and the screen is burning, roaring with the light of the sun. Steven Poole’s got a point.

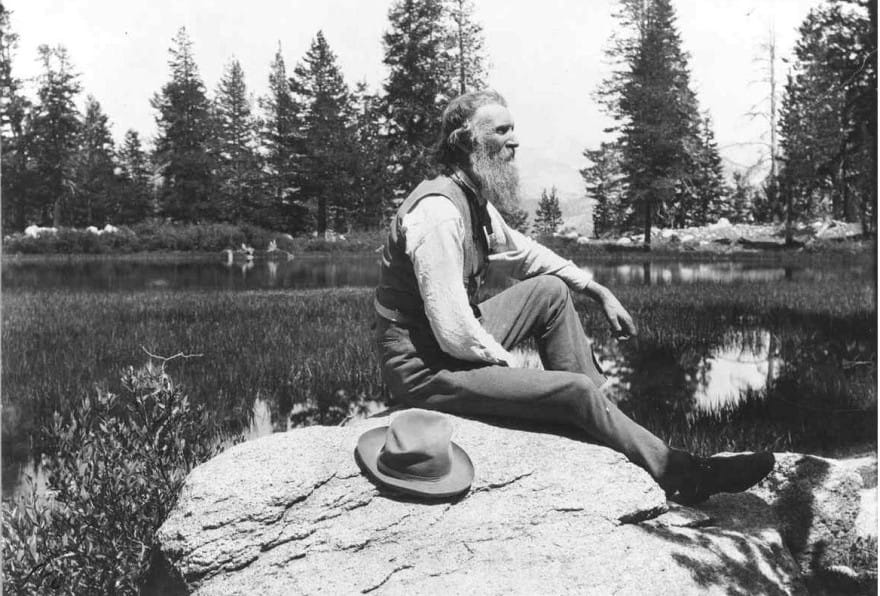

Wonder is hardwired into the history of videogames. It’s there in the labyrinthine mazes of 1997’s Castlevania: Symphony of the Night. And it’s there in the sheened cityscapes of 2007’s Mass Effect. Firewatch is part of this tradition, but it also fits into a longer-standing history of wonder and the natural world, a history borne in the Romantic movement of the 18th and 19th centuries. It’s also part of a more specific American heritage incorporating both literature and paintings, from the vast landscapes of painter Frederic Edwin Church to the words of John Muir, the founding father of the American national parks. And even though Church and Muir were documenting different landscapes—Church concerned with New England and Muir with the Sierra Nevada mountains—they share a visual lexicon.

Firewatch stands in solidarity with these representations. There are the great red mountains, coated in the rising or falling sun, and the conifers that stretch upwards with their blackened silhouettes. And that sky. Wow, that sky; it’s deep blue almost eclipsed by the constellations given free roam away from the light pollution of the city. Firewatch owes its existence, in part, to the work of John Muir and his role in the creation of the first national parks. If Muir loved those lands into the American consciousness, then Firewatch does a damn good job at trying to keeping them there.

A TERRESTRIAL ETERNITY

It’s fitting, then, that Firewatch inherits some of the fanatical zeal that characterized much of John Muir’s literary work, particularly My First Summer In The Sierra (1911). It’s a difficult read now. The style is florid, almost too much, but it conveys such exuberance, a supreme affection for the place, that it eventually wins you over. Muir speaks of how “the west is flaming in gold and purple, ready for the ceremony of the sunset… A terrestrial eternity.” Firewatch has these ceremonial moments, too. They’re there when Henry, fire lookout and protagonist, climbs out of a cave and sees the night sky for the first time, alive with stars. And they’re there when he comes across an abandoned cabin; the door falls through to reveal a vista, pines in the foreground while mountaintops stretch into the distance.

These are tightly designed moments that are hyperreal in their perfection, but they’re also distractingly artificial. Like the landscape painters of the 19th century they capture imagined moments, moments so perfect and full of drama that they couldn’t possibly have occurred in real life. Thomas Moran, in his painting ‘Nearing Camp, Evening on the Upper Colorado River, Wyoming, 1882’, went so far as to entirely eliminate the settlement that compromised his pre-industrial fantasy. And in Albert Bierstadt’s ‘Sunset in the Yosemite Valley’ and Frederic Edwin Church’s ‘Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860’, light dominates the pictures with such an elemental drama that it could only have occurred in the minds of the artists.

But for these artists, and Muir, the majesty of nature was bound up in religious devotion. These images of America present the totality of God, imbued in the world and every living thing. Muir observed that, “God himself is preaching his sublimest water and stone sermons.” He was acutely aware of the deep history of the place, of the way in which hefts of rock were carved by glaciers millions of years ago, how these created not only the sheer cliff faces but also the lush meadows found in the Yosemite region. And in these lush meadows he could fully indulge his botanical tendencies to discover the detail, the variety in natural life.

And this detail, that flourishing of life, is there in Firewatch’s imagining of the Wyoming wilderness. One of the first things Henry does in the game is inspect his new home, the firewatch lookout. There’s his typewriter, a nod to Jack Kerouac’s Desolation Angels (1965), and there’s the assortment of pots and pans, a thermos, outdoor paraphernalia needed to enjoy a long summer stationed in the middle of nowhere. And there on the wall is a poster detailing the common flora of the Shoshone. There are the trees: Blue spruce, Cottonwood, Lodgepole Pine, Aspen. And the shrubs: Birch Shrub, Alder Shrub, Mock Orange, Sagebrush. And there are the flowers: Prairie Fire, Filaree, Golden Aster, and the Tailcup Lupine. Firewatch inherits Muir’s eye for detail, and in doing so tells us to pay attention to our surroundings. It’s detail specific to the Shoshone National Forest, and it helps breed a deeper understanding of the place. Muir, I suspect, would be pleased.

DISCOVER THE DETAIL, THE VARIETY OF NATURAL LIFE

There are, though, important ways in which Firewatch contradicts the ethos of Muir, particularly in its attitude to exploration. Muir was never bound by predetermined routes or existing pathways. He travelled where he wanted, usually in search of some unrecorded species of plant, somewhere he felt was untouched by human interference. Muir was not even bound by mountain faces. On one particularly wild occasion he quite literally surfed an avalanche to the bottom, escaping with only minor bruises and cuts. But in Firewatch, Henry is bound by the paths Campo Santo have laid out. He maneuvers up and down the rock faces the developers say he can. Even in the meadows, usually surrounded by gentle rock slopes, he’s unable to step onto the smallest of rocks, to move off the beaten track. I know Henry’s meant to be clumsy, a bit heavy on his feet, but it felt counter-intuitive, antithetical to the naturalism—stylized, sure—the game offered. It left me feeling frustrated, duped at times, by a videogame that seemed to promise the great outdoors but wound up giving me an elaborate facade.

But Firewatch is a more personal account than Muir or the landscape painters could ever muster. Muir was looking for something in the Sierra Nevada mountains that lay away from the “clocks, almanacs, orders and duties,” of the lowlands; he was looking for freedom and meaning in “Nature’s cathedrals, hewn from living rock.” And painters such as Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Thomas Moran saw God too, but they also saw man’s personality—his potential for exploration, resilience, and conquering. Firewatch steps away from these religious and colonial considerations, these big outward looking ideas, to focus on the intimate stories we as humans bring to the wilderness.

Henry isn’t looking for anything in the Wyoming mountains other than escape. In a beautifully executed introduction we learn of his and Julia’s relationship and it’s sad, inevitable breakdown caused by her early-onset dementia. Likewise, Henry’s friendship with Delilah, his lookout colleague, unfurls gracefully through radio conversations as they try to unpick the histories of one another while simultaneously creating their own. And then there’s the tragedy that lies at the heart of Firewatch’s mystery, the events surrounding Ned Goodwin and his son, Brian. Each of these characters is struggling, unable to cope with their own social or familial pressures. They are driven to the nearest end of the world they have, the Shoshone National Forest, to escape reality.

Maybe in this regard John Muir and those landscape painters are not so different from the characters of Firewatch. Perhaps in striking out into the wilderness alone, those 19th century forebearers were leaving behind the same sort of troubles Henry is running from. Muir certainly left behind a difficult relationship with his father, a relationship that included not only beatings but “heart thrashings”, episodes of intense shaming. Henry experiences shame, too, but for his own inadequacies following Julia’s diagnosis.

CATHEDRALS OF FIRE

And honestly, Henry could do worse than escaping to the exquisitely rendered mountains and forests of Firewatch. It’s a world that delivers wonder with such frequency and to such great effect that it borders on the fantastical. But it’s also strangely limited by the potential the visuals present. Those instances where exploration is curbed, where Henry is hemmed in, threaten to derail the choice the vistas, and also the conversations, work so hard to maintain. You’re reminded, in those moments, of the inherent artificiality of the medium. Steven Poole’s metaphor, “cathedrals of fire,” holds up. Cathedrals may point to the sky, to the realm of (im)possibility, but they’re ultimately limiting; they enclose rather than release us. Firewatch is much the same. It’s a beautiful, beguiling place to spend some time, absolutely worth it while you’re there, but sooner rather than later you’ll yearn to shed its shackles, to get off the beaten path.

Header image via Wikimedia.

Firewatch image via Flickr.

John Muir image via Sierra Club.

Forest image via Wikimedia.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.