Flying high on the unfriendly skies of Hohokum

I am in an empty, inky expanse of red so bright as to appear almost violent—so rich in red it appears opulent. The hue is Caligulan in its redness; it’s cocaine red, raw meat. Other reds tremble before it; it is the God-Red.

I float through a circle, out of this beaming space, and I am in a field of faded purples and oranges. I wiggle a bit and set off at a soar, down the faded field. I am the wind that shakes tall plants; farmers hide in their hats as I sweep past; I flower the trees and rouse sleeping beasts. I find another circle, and float through it, and am somewhere else.

///

One thing I’ve accepted about myself in the past year or so is that I play games too quickly. I blast through them in a straight line. I google optimum starting stats; I fast-travel upon completing a mission to the next one; I settle, delightedly, for the bad ending. In the battle-hardened realm of Dark Souls 2, I was a cowardly, sniveling climber, sprinting from one challenge to the next and then peaking behind the shoulders of greater warriors as they felled great beasts in my name.

Wevs. I still beat it.

Hohokum, for all its sprightly exterior, seems designed to infuriate someone like me, and, I’m thinking, most of the people who play it. “It’s not fun,” people will say when they play this game. “It’s weird.” It insists upon a measured sense of pace that is absolutely alien to modern media, let alone videogames. The game consists of 15 “playgrounds,” which are large, animated 2D spaces that you move through, activating things by touching them. This is meant to be a delight, and it is—vibes sound, drums kick in, berries explode, your controller pulses. But after awhile you realize that these playgrounds are also puzzles, and these puzzles eventually need to be solved.

The catch is that you can’t; their solutions just sort of occur. I spent 20 minutes circling through a field of floating logs before I realized I needed to dong a bell somewhere far afield; all those logs, which occupied maybe 90% of that playground, never meant a thing. Donging the bell made a little widget appear elsewhere. What did it do?

This “playground logic” flies in the face of my laser-guided gaming efficiency, which is something of a global obsession for me. During long-distance drives, I cut from the inside of one curve to the inside of the next, regardless of lane, in an attempt to shave feet off the total distance. Sometimes at night I’ll stand paralyzed for five minutes, attempting to fit the five or so things I want to do into the remaining hours of the day with maximum economy. (I’ll decide: Put laundry in on way out for run, go on run, get groceries on way back, move laundry before re-entering house, shower while oven preheats.) This is spectacularly monotonous, and, I realize, unremarkable stuff. Complaining about the paucity of hours in the day is the great trite complaint of our time, but it reflects real anxieties. At Pitchfork, Lindsay Zoladz recently put it well:

These days, my daily internet behavior is depressingly predictable: Every morning I’ll click on more articles than I’d ever have time to read, clutter my browser with tab after tab after tab, and then at some moment every afternoon I’ll finally admit my own mortality and close all the things I didn’t get to. (…) I’m sort of ashamed to admit that I have occasionally caught myself thinking, “I wish I could listen to more than one thing at the same time.”

It’s that sense of mortality that hangs over our need to absorb everything. I will die with books unread—Snow Falling on Cedars, for example. I’m never reading that shit. And so I juggle a handful of games at a time, keenly aware that there are already more out there than I’ll ever play. Part of the problem is that games demand our attention absolutely: you can’t passively play them. Jamin Warren has written about how Mountain attempts to solve that problem, taking a step toward a more human-centered game design, one “that takes the life you have and builds experiences around them, and not the other way around.” One cannot play Mountain well—or, everyone gets to play Mountain well. Mountain doesn’t care.

You’ve got all the time in the world. And there are these bubbles to pop.

Hohokum, too, thwarts our efforts at optimization. Eventually, while playing it, the efficiency impulse begins firing, and the smell of a solvable puzzle wafts into the air, and the game politely stops you. Loll, it insists, with a smile. And when you get antsy again, having exhausted that playground’s tiny delights, the game says, slightly louder and clearer, and this time not smiling: Loll.

And so, eventually, you do. You loll. You pop the bubbles. You re-build the rollercoaster by doing things like activating some lights hanging over in the corner. You find a key; it does nothing. You pop a lot more bubbles. At one point you pop bubbles for like fifteen minutes, the soundtrack at a vague ambient hum the entire time, until you sort of somnambulantly pop the final bubble and the screen erupts in an enormous Swedish disco orgasm. You enjoy this for awhile, then you go back to the rollercoaster thing. It has reset. You find more bubbles. The neocon businessman Jack Donaghy, on the sitcom 30 Rock, once advised, “Never go with a hippie to a second location,” the idea being that you have then ceded control of your day to someone with no control over theirs. Hohokum emulates the feeling of going with a hippie to a second, and then third, and then fourth location, ambling from one curious errand to another, until eventually your sense of time has collapsed, and you are on the hippie’s clock, and you are on the hippie’s couch, and your phone is dead, but why worry?, you tell yourself. You’ve got all the time in the world. And there are these bubbles to pop.

When people call Hohokum weird, this is what they’re talking about: not the amount of time Hohokum demands from you, but the lurching, alien way it demands it.

///

I stumble through a circle and happen upon an enormous wedding cake rising out of an ocean of wine. It’s night, and synthesizers pulse as softly as the stars. We are all hazy with wine, and love is in the air. I unite a bride and groom and I pour wine into the mouths of the attendees. We grow hazier. There is wine. There are synthesizers.

Minutes pass.

///

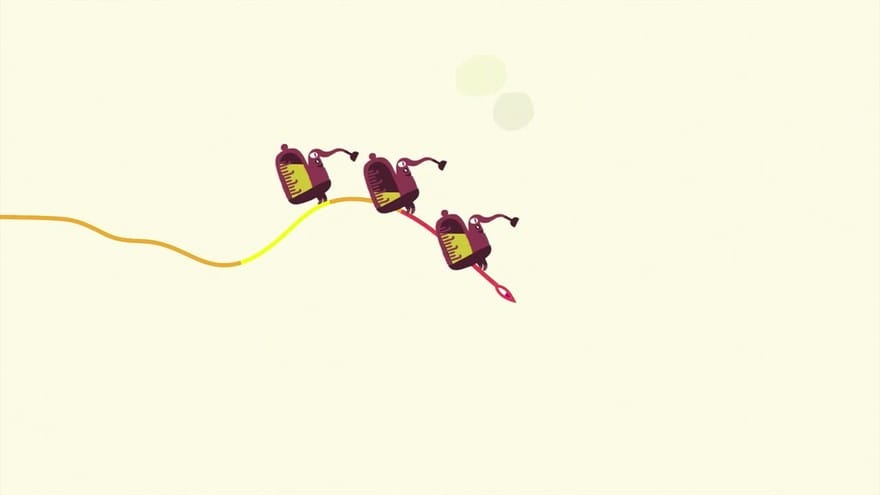

Anyway: good god, is Hohokum pretty. Artist Richard Hogg has designed a superflat world of decisive palette—cream, that omniscient red, a handful of cool blues and purples, each taking turns dominating the screen. We glide through these as an eye on a string—an instructive choice of protagonist. The colors are arranged across strange assemblages of architecture. A cave, dotted with butterflies, spirals out to a series of floating islands. Long lines of foliage dangle from enormous Indian statues of elephants and turtles. I get trapped in some graph paper, a set of breakable boxes that appears to be making fun of traditional game design, then I go to outer space. Then I go inside of a bubble. You get the picture.

It is probably the game’s greatest accomplishment that it manages to match this palette with this soundtrack—which kicks and floats, all xylophones and skittering beats—without being insufferably twee. It is exactly one “story scene” away from sucking, some grand Poo-Ball telling us to unite the village or whatever, and mercifully that story scene never comes; the colors and the music remain unimpeachable and uninterrupted. Characters (more eyeballs on strings) are introduced with names like Eli and Harriet in single-screen flashes, providing backstories that blissfully disappear on impact. We go right back to whatever we were doing—which is, typically, whatever.

But Hohokum ultimately pulls its punches. You can do whatever, if you want, but eventually you’ve got a puzzle to solve. Bad puzzles are easy to design; good puzzles (whether easy or hard) require logic, care, even a touch of the narrative Hohokum pointedly rejects. Good puzzles tell a story in their physical parts. Over time, Hohokum demands story, even as it tells you it doesn’t have one, and it demands progress, even as it works so hard to act like it doesn’t. Mountain’s pause screen, too, claims that keyboard and mouse both do nothing, when in fact they move the camera and play music, respectively. Mountain needs to embrace what you can do in it, and Hohokum needs to embrace that it does have goals.

As these and other games etch out a future for this medium—one which does not demand mechanical fluency and unlimited free-time—they could look to snark less at the mores of the form. It’s sort of like waking up on that hippy’s couch the next morning as she heads in to work, shooing you away. It’s all well and good to have a job, and I should be heading to mine, too. But why didn’t you tell me you have to work? Why did you invite me over in the first place? Which person are you, and which one are you hiding from?

///

AFLOAT IN A SEA OF RED WINE, LATER—Everyone is drunk, everyone is in love, and I am bored of this party. I do curlicues in the starry sky. I touch my controller, and it sings to me. The ocean bobs down, and I, eye on a string, spot it at last: the switch. My ticket out of this joint. I barely have time to wonder what sort of clown architect would hide something so important below sea level, but what do I know: I’ve been drunk for days.