Four Things I Learned While Writing a Book about Super Mario Bros. 2

Editor’s Note: Our long-time writer Jon Irwin recently published a book documenting the artistic history and legacy of Super Mario Bros. 2. It’s available now, via Boss Fight Books. We asked him upon its release what he learned digging so deep into a single game.

—

Out of all the sequels in the Super Mario series, the longest-spanning, most consistently popular and highly acclaimed game franchise in history, Super Mario Bros. 2 is the strangest and most important.

Twenty-six years ago, the videogame starring Mario and three of his friends landed on American shores with a resounding roar. That first game was a phenomenon, the likes of which happen once or twice a generation. Super Mario Bros. for the NES would soon become the best-selling game of all time. It sold Nintendo’s first console in the West on the promise of arcade-quality games in the home. In the course of a few years, Mario had gone from the anonymous rescuer in Donkey Kong to the leading face of an entire industry, bounding into the mainstream off a wave of branded products, a Saturday Morning cartoon, and a big-screen advertisement masquerading as a Hollywood movie.

Had Super Mario Bros. 2 been a big ol’ Bob-Omb, though, none of this would have happened.

While writing a book on the game, I sifted through the past twenty-five years to explore the story of this pivotal, underappreciated and misunderstood gem. Here’s four things I learned.

1. If Harvard Business School accepted one different applicant in 1983, Nintendo’s fortunes may be dramatically different today.

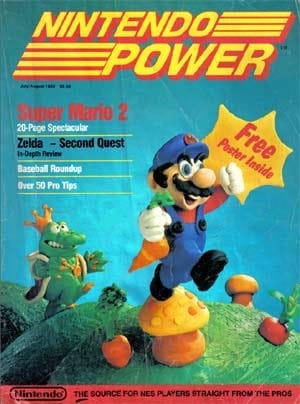

Gail Tilden worked at Nintendo of America for over two decades. She helped launch Nintendo Power, the first game magazine of its kind in the west (helped along by a clay-sculpted cover for Super Mario Bros. 2). She was instrumental in taking Pokemon out of Japan and selling it to the rest of the world. Her final task was spearheading the marketing campaign for the Wii. She left the company in 2007, Nintendo at the peak of its innovation and success.

In an interview, she told me that she almost left the company after months. Her husband was awaiting a response to his application to Harvard Business School; she took the job with Nintendo but told her Redmond, Washington-based employer she would have to quit if her husband began school in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Lucky for her, and the House of Mario, Harvard said no.

2. The Character Select Song is longer than you think.

Not all research yields history-shaking what-if scenarios. A good amount of my time working on the book was spent playing the NES game, but also listening to it. Certain in-game songs provided the requisite inspiration for, say, a chapter on composer Koji Kondo’s contributions to the medium. One track in particular surprised me.

A significant addition to Super Mario Bros. 2 was its ability to play as one of four characters. As many players have come to know, SMB2 was in fact a reskinned version of a popular Japanese game, Doki Doki Panic. (Director Kensuke Tanabe, in an interview with Wired’s Chris Kohler in 2011, let slip that Panic was actually based on a tossed-out Mario prototype; all those who proclaim SMB2 as “not a Mario game” do so on thin ice.)

The second screen you see after powering on the game portrays four characters framed by red curtains. “Please Select Player” the text reads. A charming ditty plays, sounding like background muzak for a game show. Mario, Luigi, Princess Toadstool, and Toad stand before you, awaiting your choice. Each character’s strengths are different. Luigi jumps higher, Toad runs faster, the Princess can float. You likely knew this.

This videogame from 1988 still has secrets to share.

But did you know that if you do not immediately select Toad (the clear choice), and instead sit on that screen for longer than two phrases of the initial riff, the song transforms and goes into a tiny bridge that veers toward the hallucinogenic before returning to the opening bars and repeating ad nauseum.

Maybe you’ve heard that part of the song a thousand times. I had not. It made me realize how many tiny corners of games are left underexposed, never to be seen or heard by its players. And if this relatively simple videogame from 1988 still has secrets to share, how rich and vast must the games of today be?

3. You can jump in mid-air.

During the course of my research, I was lucky enough to meet and talk with Andrew Gardikis, a kind young gentleman who lived an hour south of my then-apartment. He also happened to hold the world record speedrun for Super Mario Bros. and, at one time, Super Mario Bros. 2.

I might have written the book on the game, but Gardikis wrote the TAS—that is, the Tool-Assisted Speedrun, a video produced via emulation that allows the runner to methodically plot out the exact fastest route through the game. By slowing down the action, sometimes to the single frame, one can manipulate the game in ways near-impossible to reproduce during a normal run. Doing so can uncover secrets or tricks otherwise unknown, some of which can be used in an official attempt.

The game program translates that data as something it’s not.

One trick he showed me was a simple maneuver that, if employed in specific spots, could cut down your time dramatically. If you run toward an enemy and jump right before you hit them, you can, if done correctly, jump again in mid-air. Your character sprite overlaps slightly with the sprite of the enemy. The game program translates that data as something it’s not, e.g., “Luigi is standing on a Shy Guy.” You can normally jump while on top of enemies. Now, even though you’re soaring through the air, that slight overlap causes the game to think you’re still on solid ground. So you can jump again. And possibly attain heights allowing you to skip a section of the level, making your overall time faster.

4. There’s more warp zones yet to uncover.

After a year of research, playing, writing, and re-writing, there is still so much about Super Mario Bros. 2 I don’t know. Nintendo keeps a tight lock on the doors; many documents and records remain inaccessible. With Nintendo’s history and their continued ability to recycle ideas in novel ways, the influence of Super Mario Bros. 2 becomes a fluid, living thing.

I recently stumbled upon a writer with a self-professed obsession to the very subject of my book. One hypothesis from his blog damn near made me breathless: that the fairies in Super Mario 3D World (2013) were descendents, at least artistically, from the tiny creatures in Super Mario Bros. 2 known as Subcons you see only once, during the end sequence, for about four seconds.

Images and ideas will continue to fold over themselves in ever-richer ways.

The real-world consequences of this connection are less than nil. These creatures have the same genetic makeup of any artist’s flight of fancy, which is to say they do not exist. But the callback is thrilling because of what it suggests. Videogames, as a medium, have been self-aware for some time. But it takes time for these self-referential nods to gain meaning. Entering their fourth decade of mainstream acceptance, images and ideas will continue to fold over themselves in ever-richer ways. Paul Simon was only able to write Graceland because of the pre-existing rhythms of another culture’s music. Hollywood’s golden age of the ‘70s lifted traits and cues from decades past and subverted their meaning; Casablanca’s romanticism begat Chinatown’s nihilism.

We’re finally reaching that point in games: It was only six years ago that both Braid and (Super) Meat Boy gave us refracted visions of what a modern-day Mario could look like. Such connections can be made beyond fellow developers, though, and become starting points for the kind of critical analysis or personal reflection taken for granted as necessary responses to other mediums such as music, film and literature. As they continue to evolve, videogames demand close, careful attention—even if, sometimes, it was all just a dream.