It must be difficult to make digging—a naturally repetitive and laborious activity—enjoyable. Do you remember your first digging game? Mine was Watch Out Willi!, an enhanced PC port of Atari’s Stone Age Deluxe. Willi, represented by the disembodied head of a caveman, had only one desire: to eat cabbages. Despite the basic motivation, traversing the cabbagepatches required a bit of finesse, digging away dirt and pushing boulders to reach the leafy greens unscathed. The environment did not disrupt flow; it was a source of it. Constant cabbage collection produced a feeling of accomplishment and forward momentum.

I rode high on the whimsy of getting lost—up until a point.

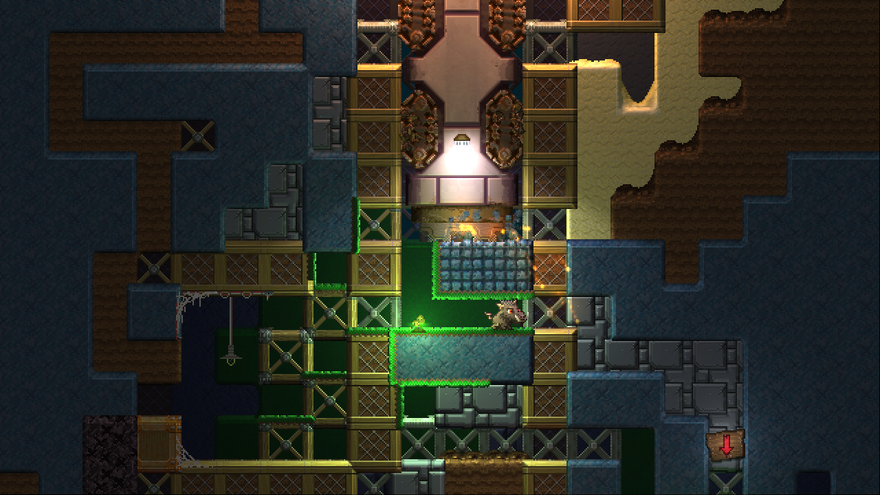

By contrast, Full Bore literally dropped me into a huge excavation site with little explanation where to go next. My new boss, accusing me of thievery, told me I needed to recover his gems. Scattered throughout the game, these took a decent amount of digging strategy to reach. But those puzzles did not propel me so much as the simple joy of digging with no particular direction or purpose. There’s a certain satisfaction in clearing a path through earth that seems impenetrable at first glance. Those dirt tiles were no match for me, a small but fully capable boar. Slamming my head into the ground and watching nearby sand tiles disintegrate was a tangible delight, as was manipulating solid rock walls into staircases. I aimlessly explored dozens of areas, collecting gems as I felt like it. I rode high on the whimsy of getting lost—up until a point.

I happened upon a boar with a welding torch. He offhandedly told me he needed something to get his machine running again. Until now, the one-sided conversations with the other boars had been flavorful but inane, so my immediate reaction was to shrug the request off as more window dressing. After cycling through the areas I had already explored a few times, I realized this was serious: the guy needed my help, and I needed him to be helped. And so I learned that those gems I had been happily collecting thus far were useless. Two options became clear: I could either continue solving puzzles for gems in the mines, or move the story along and open up fresh areas to explore.

This feeling, of being pulled in two directions, stuck with me through most of the game. The story tugged forward, the collectibles rooted me to the spot. The gems may have been the initial motivation to dig, but they never came up in meaningful conversation again. After a few screens of messing around with blocks, I was far more interested in speaking with an easy-to-get-to character than dislodging the gem a few levels above him. This also applied to the scattered computer terminals, which spoonfed cryptic messages in a manner not unlike those in The Swapper. The messages didn’t make much sense on their own, but together they attempted to explain the supernatural elements of the game, including its convenient warping stations. As the story revealed itself to be more grandiose and otherworldly, I cared less and less about those once-alluring gems.

Getting lost in this game is equally fun and frustrating, in almost exactly even measure.

Eventually I didn’t care about them at all, because finding a new area to explore felt like a soft reset for my nerves. My core skills never changed, but at least Full Bore consistently introduced different types of tiles to play with throughout the game—laser tiles, crumbling tiles, exploding tiles—I had the chance to play with all of them, whether I gunned down the main path or spent some time chewing on the side puzzles. But after agonizing for 10 minutes over one stuck gem, I had to move on. (I had to overcome my sunk-cost syndrome and pretend it wasn’t there). The climax of the game locks you into short, self-contained puzzles that directly challenge all of the digging knowledge you’ve acquired in the game. I relished this section, freed at last from the game’s labyrinthine map.

The majority of Full Bore is a balancing act—charging blindly through the map may incite agoraphobia, while obsessing over a particular nook for too long yields claustrophobia. Getting lost in this game is equally fun and frustrating, in almost exactly even measure. I would have liked a little more direction, moving through these extremes. Then I could just do what I, and digging games, do best: I could dig, confident in the knowledge that I was headed in the right direction. As it was, though, I’d have to try find the flow of dig-and-push myself and let it carry me away. Whenever I felt stuck, or questioned why I was digging, I took a break by running myself into a solid wall. My determined boar rammed its head into it over and over as I held down the directional key. Watching that for a moment usually gave me enough reason to continue.