Gabriel Knight and the birth of mature storytelling in games

The praise of a “mature storyline,” most evident in reviews and critiques for videogames and Young Adult fiction novels, tends to be somewhat tricky terminology. Because while it may sound like a compliment, the distinction is usually only made when critics have become accustomed to otherwise juvenile material. Always, the “mature storyline” compliment is given with an air of surprise. In tones that say, “Oh! I didn’t know your type could be relevant to actual life. How quaint.”

But the terminology usually points to a slow but steady path of legitimization for a medium in the eyes of mainstream culture. The recent surge in readers, writers, and consequent quality of Young Adult fiction, for instance, surely stems from a decades-long process of de-stigmatizing the genre. The movement’s gained so much momentum, in fact, that lengthy, dissenting opinion pieces against it are already cropping up in the likes of Slate magazine.

Games seem to be experiencing a similar momentum, receiving more and more critical attention by Time and The New Yorker. But arguably, a lot of the medium’s flux can be traced back to unlikely early sources. Jane Jensen’s release of the classic point-and-click adventure Gabriel Knight in 1993, for example, was one of the first time games ever received the “mature storyline” label. The tale of a New Orleans ladies-man turned detective into voodoo-related murders, featuring tasteful uses of violence and a romantic subplot that managed to titillate rather than look laughable, was virtually unseen in other videogames of that time. Now, after Gabriel Knight’s recent re-release, and with the distance of a couple decades’ reflection, it’s time we understood exactly what made it such a singular story in the medium. And to do so, we’ll have to highlight an attribute not often associated with mature storytelling. Because Gabriel Knight’s biggest gift to videogames remains, without a doubt, the ideal model for a hot male protagonist.

Gabriel Knight remains, without a doubt, the model for a hot male protagonist.

In an article entitled “WRITING HOT MEN FOR GAMES? Yes, please,” Jane Jensen defends her tendency as a developer to write mostly male characters, in response to those who would criticize her for not tackling the underrepresentation of her gender in the medium. “The truth is, when I write a male character I am writing him from a female perspective, as a kind of fantasy,” she explains. “I write male characters who are hot simply because I enjoy it.” (Emphasis hers.)

In a medium where most protagonists are male and, well, beefy, you’d probably assume the “hot male protagonist” trope would be rife. But you’d be wrong. Because, as Jensen explains in detail, the qualities of a true HMP (hot male protagonist) are far beyond that of the male power fantasy evident in most other game narratives. Sure, Duke Nukem may have the biceps for the job. But when I play as him, I get the sneaking suspicion that he wasn’t created with me necessarily in mind—not even a little.

Yet sometimes, whether by happy accident or because of queues picked up from other mediums, game studios have caught glimpse of the HMP as Jensen (and I) qualify him. And boy does it make a world of difference. Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, for example, was the first game with heavy combat I ever managed to play as a young girl all the way to the end. And you can bet your ass I wasn’t sticking around for the game’s female companion, Farah.

I stuck around because I’d fallen head over heels in love with an unnamed, arrogant young prince. He wasn’t your typical prince—not the Disney kind, anyway. He made lewd jokes, and seemed somehow attractively tragic. I had to keep playing, no matter how much I struggled with the combat. Because my prince was telling me a story: how could I possibly abandon him before reaching the end? In Sands of Time, you see, the game’s narrative is framed by the prince’s narration, as he retells the story to some unknown audience. It’s a brilliant device, allowing us to see past his otherwise off-putting egotism, giving him moments of human vulnerability, and even sprinkling the action with enough romance to make it one of the more relatable storylines I’d encountered in a game until that point.

The ending of Sands of Time reveals that the prince has been retelling the story to the companion who had been beside him every step of the way. Due to some time-reversal shenanigans, Farah can’t remember their adventure together. So the prince must recount their harrowing journey to the very woman he ended up falling in love with. In this way, a female audience frames the entire story of Sands of Time. And maybe that’s why it, along with Gabriel Knight, is lauded as an earlier example of “mature” storytelling in videogames. While they may not have been from a woman’s perspective, these narratives certainly didn’t ignore the female gaze like so many other games did (and still do.)

You can imagine my sense of betrayal once that game’s sequel came out, and my prince inexplicably became a petulant, brooding, uncharismatic emo-bro. What had happened to the intimacy of Sands of Time, those moments of vulnerability that had rendered my prince a true HMP?

Well, for starters, the female frame was gone—if not eviscerated. In fact, the closest the sequel came to a female “character” was an Empress of Time who was more jiggle physics than person. And while the Empress might’ve served someone’s fantasy, she only served to remind me of the target audience I wasn’t a part of.

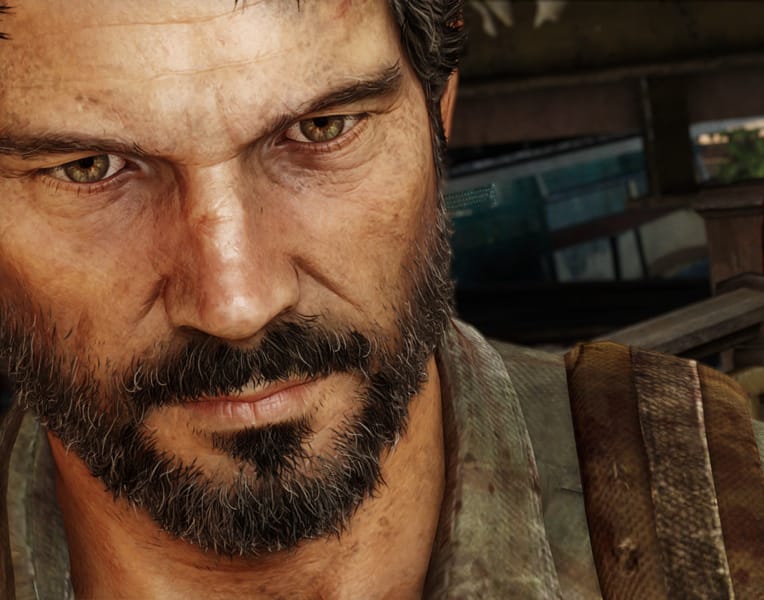

As Jensen points out in her article, companion-oriented narratives have recently become a way for game designers to tell stories that aren’t from the female perspective, but at least address it—while also including plotlines broader than the realm of pure machismo. The “boy-gets-girl-boy-loses-girl-boy-gets-girl” trope, evident in both Walking Dead and Last of Us, is a trope Jensen traces back to typical romance plots. Both those examples show how the shift needed to solve the underrepresentation of women in games is not about the number of female characters on screen. Because my sense of exclusion in Prince of Persia’s sequel didn’t come from the protagonist suddenly changing sexes. It excluded me because the female perspective suddenly became irrelevant to the entire Prince of Persia universe.

Games like Gabriel Knight and Sand of Time, as well as The Last of Us and The Walking Dead, all represent more than just good storytelling for the medium. They’re games who’s narratives incorporate a more realistic spectrum of perspectives, a perspective that goes beyond the so-called target audience. Gabriel Knight made people stop and say “I didn’t know games could do this” in 1993 in part because most game narratives in 1993 did not bother addressing the needs and desires of more than one aspect of gender. When other games did try to address more than one gender at the time, it usually went about as far as slapping a bow onto a yellow ball and calling it Ms. Pacman.

Game narratives are finding legitimization in broader culture just like Young Adult fiction is finding legitimacy in literature: by speaking to layers of perception outside a single demographic. As author Meg Wolitzer says in a recent New York Times article, writing YA fiction feels like, “I’ve been given access to a pure form of the complications involved with being young, now filtered through the compassion, perceptions (and barnacles) of my older self.” That hybrid perspective, between young and old, has allowed YA fiction to reach people in ways High Literature (capital H, capital L) never really could. With a broadening audience and growing list of contributing authors, the genre seems to resonate with whoever is or ever was a young person—which is everyone, right? According to Wolitzer the YA “book in your hot hands at that very moment solves all your desires and needs,” regardless of age. Just like Gabriel Knight’s hotness satisfies the ladies-man fantasy, as much as it satisfies the ladies-who-like-sexy-men-with-southern-drawls fantasy.

Gabriel Knight’s hotness satisfies the ladies-man and ladies-who-like-sexy-men-with-southern-drawls fantasies.

I’m not saying that the solution for more mature game stories lies necessarily in getting more female developers writing more HMPs, though of course that never hurts. Sands of Time, Last of Us, and The Walking Dead were all games written mostly by men—and I wasn’t the only one who found their male protagonists more relatable or datable. What’s most valuable is aiming for multi-gendered and multi-personed approaches to storytelling, rather than zeroing on the assumed needs of a small percentage of players.

And if that means more HMPs in tight jeans, then I’m sure you won’t be hearing any complaints from either me or Jane Jensen.