The gamer-core nihilism of Earl Sweatshirt

Earl Sweatshirt has just released the best album of his career. It glows, instantly apparent, off of I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside, which the 21-year-old emcee produced largely by himself. Mostly, what you hear on the record is Earl moving out from under the tutelage of Tyler, the Creator, the supposed leader of the Odd Future clique. Tyler has always been an insufferable fuck, the type of endlessly familiar, internet-born Angry Young Man™ that spews rape jokes and calls you a faggot when you don’t laugh along. The subtext of many early Odd Future thinkpieces insisted that IRL the gang was just the product of a damaged world—look, they’ve got gay friends—but there were other indications that IRL Tyler was a bully, quick with a tackle or a headlock, and a Bieber-esque boy-prince, insistent upon his own every whim. One important early piece dubbed the crew “the /b/ boys” for their ability to fuse 4chan troll culture and hip-hop. “There is no compass,” Sean Fennessey wrote of their morality, “other than, maybe, the Internet—and the Internet has no compass.” This corporate brattiness drowned out the more interesting voices of the group.

Earl, for example: he, too, is an awful person, but he’s a talented one. Even his earliest and worst releases showed an uncommon love of language, words tumbling in delirious cartwheels over each other. That Tyler does not appear for a single second in any capacity on I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside, and that it is also Earl’s best record, is not a coincidence, is what I’m saying. Earl has called it his “first album,” and it feels like it. It’s his first without Tyler.

Image via Cam Evans

Tyler also doesn’t smoke pot, which I don’t trust in a rap producer. I do not have this problem with Earl: this album is in many ways a paean to the drug, as you may tell from the title. He has referred to the album as a snapshot of a period of remarkable depravity, in which he retired momentarily from the public eye, drank endless amounts of Hennessey and smoked pot for days at a time. From deep within that bombed-out wash of intoxicants he’d punch out beats and rise to breathe out effortless verses, which eschew the endless Eminem assonance of his early work for lived-in but no-less-gnarled rhyme schemes. While Em (and even current Kendrick) might lean into every syllable, Earl shows a Danny Brown-like faculty of performance, with a deeply emotive delivery that rises and falls in accordance to those knotty rhyme schemes. The rare two-verse track “Faucet” exhibits this entire range in just three minutes.

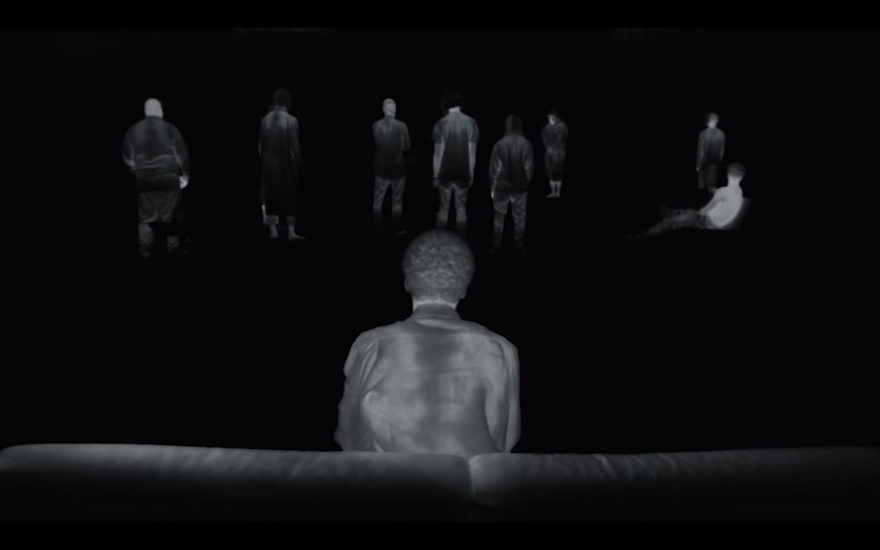

It all has, in the laser focus of its intoxicated, boyish anger, the feel of wandering into the wrong comments thread, or pairing up with some half-ass clan in an online shooter. And yet there’s pathos bleeding out of the record. At times it feels like a wry, indoors-kid parody of a rap album; “Inside” is all golden-age shimmer, with somnambulant “Hey!”s that hit like a low-bitrate clip from Yo! MTV Raps. The Silent Hill synthesizers of “Grief” evoke not the game’s torture-porn horror but its protagonists’ unbearable melancholy, which is made even clearer in the video: a glimpse into the bro-cave of blunts, couches, and dudes holding controllers. In one shot Earl is shown sitting on the couch, seemingly miles away from the other people in the room. The weed and the passive attitude toward whatever’s on the screen are a vessel for dissociation, almost a submarine. His previous album, Doris, was named after his grandma, who died during the recording. Here he submits to that grief.

Even the warped VHS lines of the cover art suggest loss. Early Odd Future efforts felt like haunted houses in which the jump scares were rape jokes; this album feels like a physical space very literally inhabited by ghosts. Earl’s grandma sometimes alights on the couch next to him mid-verse; he passes her the bottle, unfazed. Rappers have been lionizing their moms and grandmas forever—the Clipse briefly celebrated their grandma for teaching them to sell drugs, then apologized to her for sharing the family secret—but the women in Earl’s family are refreshingly human. His grandma’s death hangs over the entire record’s sense of malaise, but, as with real grief, she comes up in passing, in small ways. His sentences seem to glitch to include a dead person. Why go outside when the people you want to remember are haunting your living room?

His attitude toward his mom is even more singular. She was once vilified for sending him to a reform school in Samoa (what Earl has called “baby prison”), but here he treats her not as antagonist or saint but as his teacher, a sort of intellectual north star. He told NPR that he’s proud to play the record for her, despite its darkness and ugliness, because “it’s clear”—that that marks it as worthwhile and different for her. The other great rap album of 2015, Drake’s If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, provides a similarly direct portal into the psychological topography of an asshole. Like Drake, Earl has triumphed over douchiness by virtue of clarity.

But while Drake’s brand of louche loathsomeness can be traced back to at least Parisian parlour culture, Earl’s problems—and triumphs—are more urgent. In 2010, Fennessey called Odd Future “the perfect rap crew for our time: Where we all live on the Internet, alone. … Where you can say anything and hide in the shadows of blog commenter anonymity or meme Tumblrs or fake Twitter accounts.” These were unscrupulous but innocuous people at the time, but in 2015 the light is much harsher; we know how startlingly literal those threats can be, just how legion those anime avatars and Guy Fawkes masks are, how at a certain volume Twitter threats become actual assaults. But if Tyler is the poet laureate of the Gamergate set, then Earl Sweatshirt sounds increasingly like their redemption. Hip-hop held his toes to the fire, and he relented. The pursuit of dopeness yielded clarity. The angry young man has found an anthem; more interestingly, he has found a mirror.