Gareth Wrighton: Breaking Fashion's Virtual Reality

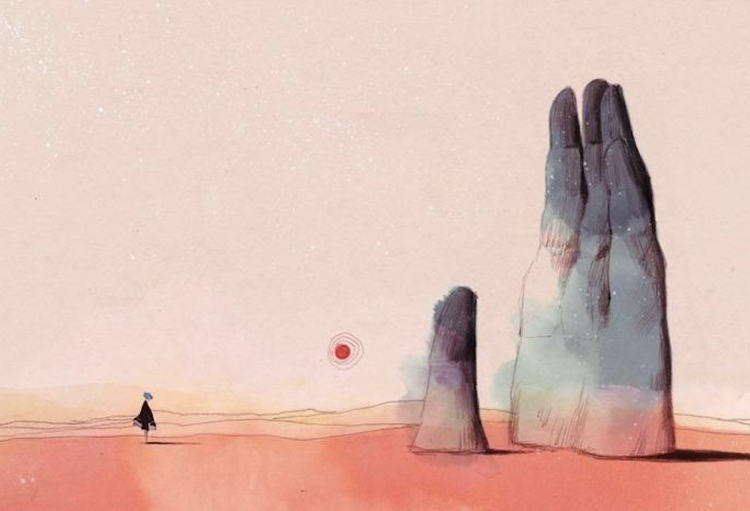

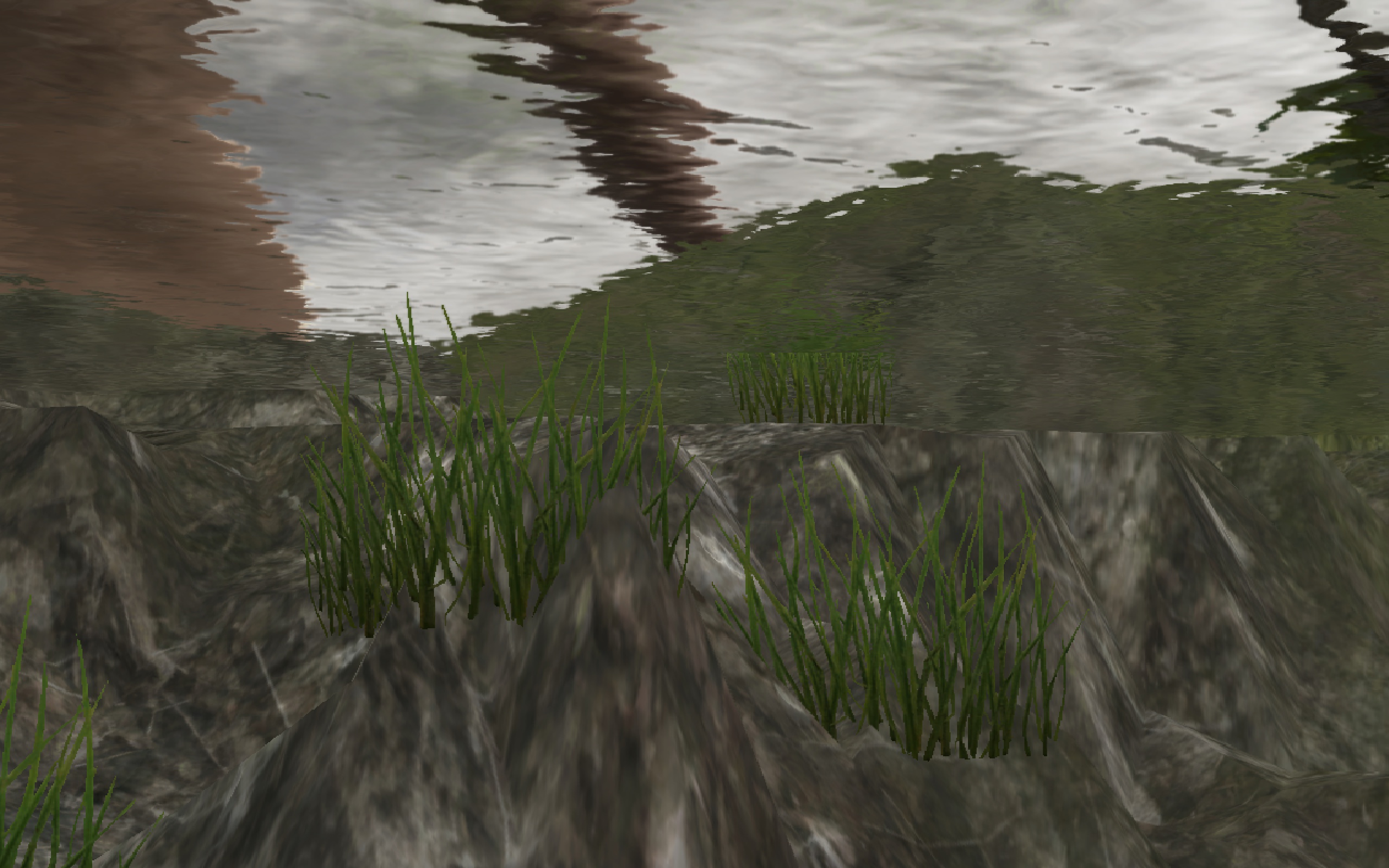

For Gareth Wrighton’s final project at renowned fashion school Central Saint Martins, those parading his garments weren’t statuesque models. They were zombies roaming around a derelict shopping center. While his peers crafted printed magazines or designed websites, Wrighton presented his designs through a post-apocalyptic, anti-capitalist computer game titled The Maul. Viewers traverse a decaying 3D environment built in Unity, interacting with Wrighton’s knitted garments as lo-fi, pixelated, digital objects. Since then, The Maul has manifested as a tangible runway collection and will re-emerge later this year as an expanded online store.

For the London-based designer, it is critical to think of garments both as objects and images. We sat down with Gareth to speak about what it means to make work with digital dirt and detritus, how glitches in game engines serve as design inspiration, and how fashion is inherently—and has always been—virtual.

You went to Central Saint Martins for Fashion Communication, and The Maul was your degree project there. Can you talk more about the origins of that work?

I applied to Saint Martins in 2011. I thought I wanted to do fashion design, but you try everything out when you get there. I realized how much I loved fashion photography, and there’s a great pathway within the Design degree called Communication. It’s everything except making clothes—the imagery, websites, styling. The people in my class are some of the most exciting young talents in fashion now. It was a proper, old-school fashion education.

The outcome of the course is to make a magazine. It takes a whole year—you find your passion project. I got this itch to do a video game as a magazine. There were loads of impetuses to it, but the main one was this idea that printed magazines are bound by a spine; a cover. There’s a linearity to the way you go through it. I thought, Oh, that’s so stale. It’s the same with fashion film; there’s a final render or edit with a beginning, middle, end. So I thought, Well, what if I built a 3D environment?

It’s up to the audience to explore it in their own way. I latched onto the idea of dead malls, which are dying because of online shopping. I thought it would be beautiful to recreate the architecture of those spaces as destroyed, decaying. What would it mean to build that meticulously in a game? To make something that’s falling apart and defunct, with the character you play running around it wearing clothes that I had made?

You’re also a self-taught computer programmer and video game designer. How did this DIY education shape the more rigid, formal education at CSM?

I hated studying design at college because it focused on designing clothes I wouldn’t want to wear.

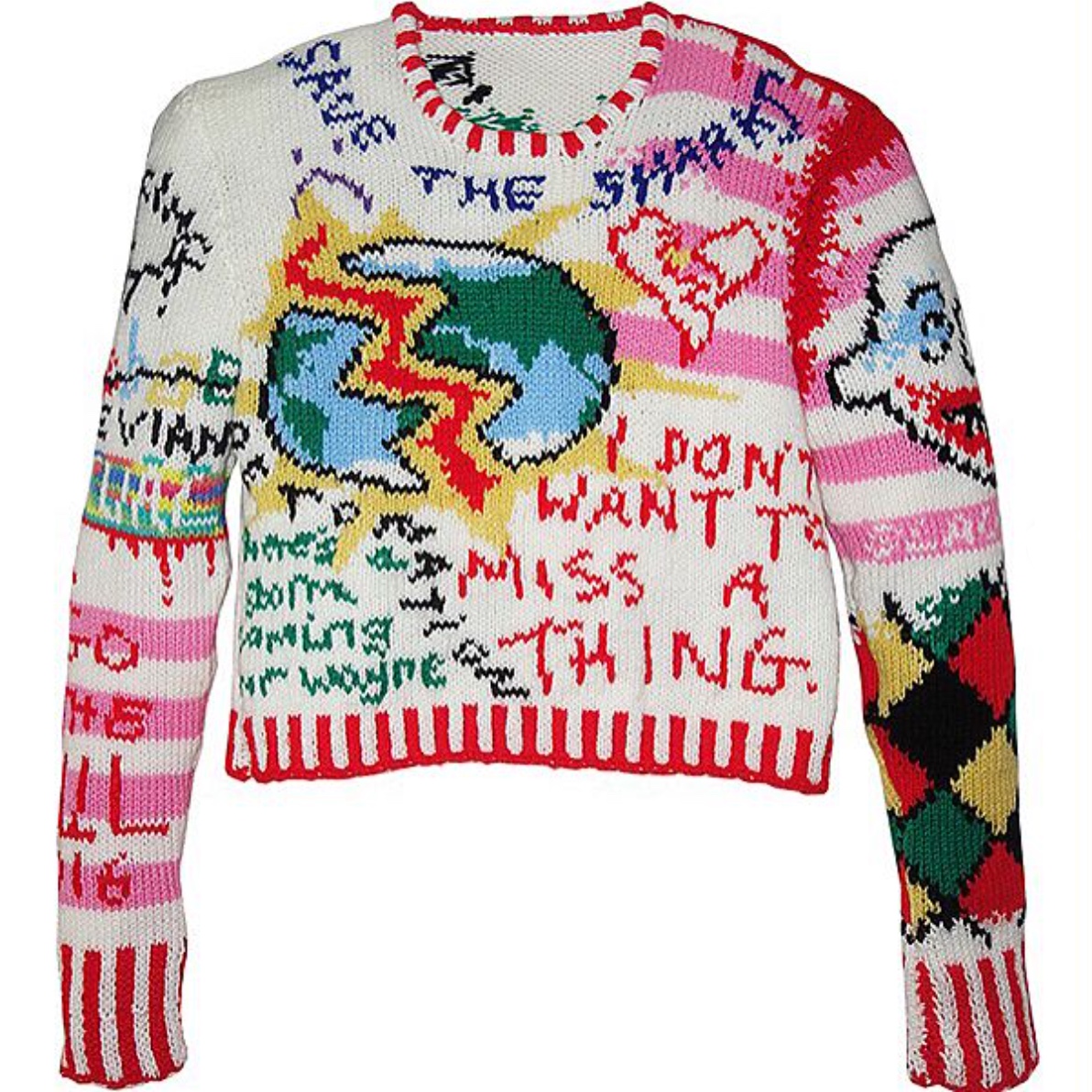

I watched lots of knitting tutorials on YouTube. The clothes I make aren’t innovative or groundbreaking, but it’s what’s going on within the materiality, which is where my ‘journalism’ is. I’m making jumpers, and the power in that is that jumper is pixelated.

I made The Maul on Unity, which I also learned through YouTube tutorials. I’m reluctant to call it a game … the plot is there is no plot—it’s this decaying monument. Anytime I had to do something new in the engine, I was YouTube-ing it. It was amazing, the YouTube Unity scene in 2016.

The way you use decay and degradation as a motif throughout your work is interesting because digital has a connotation of being ‘perfect’ or technical; seamless or sterile.

I’ve been obsessing over what is the grunge equivalent to digital fashion. That’s what I really want to play with—not remaking grunge, but the ethos of grunge, the apathy, the angst, the lo-fi. What is digital dirt? That’s what The Maul is to me—it is falling apart at the edges, amateur. It reminds me of the way kids made album covers on a Xerox machine. Unity is free—it’s such an accessible tool! I couldn’t afford to fly a plane to an American shopping mall, so I had to make it digitally.

That was the impetus behind making the Maul as a video game: using whatever’s around you, downloading free third-party assets. It’s the same as cut-and-paste collage. I was also obsessed with apocalyptic cinema—Michael Bay movies and narrative tropes in video games. It’s such a fun motif to play around within the fashion sphere, which is refined and crisp. That’s something I doubled down on when I started showing tangible fashion shows. How can I embrace these horrible, dark themes with a flippant attitude?

Environmental details from "The Maul" (2016).

The Maul started as a video game. This past year, you re-fashioned it into a tangible fashion show on the runway called ‘A Day at the Maul.’ What was this translation process like from the game space into the real world?

The live-action Lion King was in the cinema at the time [laughs], and I thought, I need to remake one of my projects. With the original iteration of The Maul, I spent 120 hours hand-knitting a jumper, but you could only interact with it through playing the game—so it was this degraded pixelated, blurry object. And I thought, I’ve done the animated one, let’s do the real thing. Let’s take advantage of the runway. That was The Maul live-action.

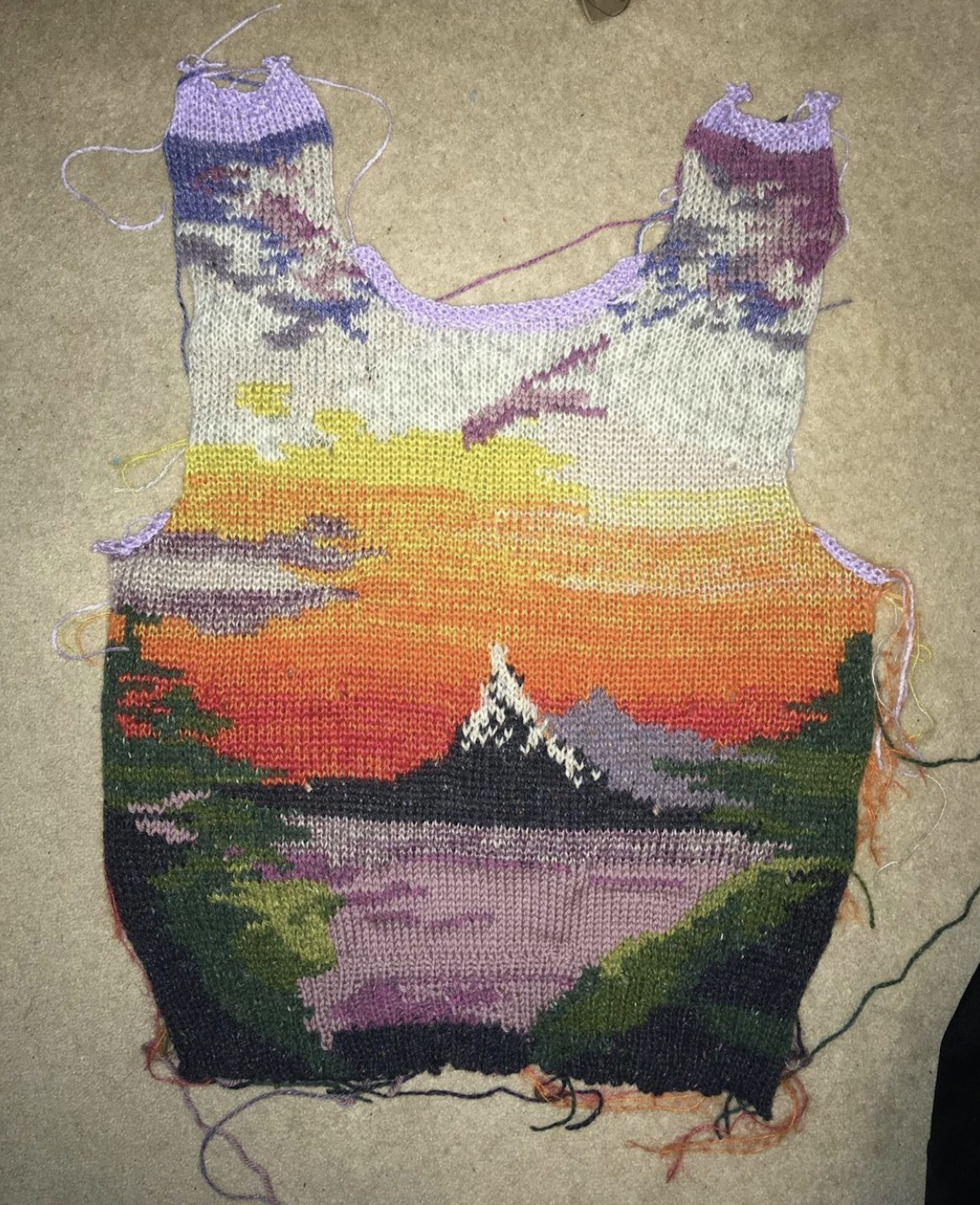

On the topic of remaking, your process often incorporates multiple rounds of interpretation; of translation across digital and physical mediums. One jumper is your interpretation of Jenna Marbles interpreting a Bob Ross painting—it’s similar to computer programming in how it’s iterative. Can you talk more about these layers of translation in your pieces?

Jenna Marbles is an iconic woman. She is the 2010s to me; the perfect reference of that time. It’s an intricate jumper—a virtual landscape, one that’s come from my head, and no landscape in particular. I was watching Jenna Marbles following a Bob Ross painting tutorial. Then people started uploading videos of themselves following Jenna Marbles following Bob Ross. It’s that shared thing on YouTube where it becomes a web, and things get so spread and disparate. I thought, It’d be so bloody meta if I followed on my knitting machine, Jenna Marbles following Bob Ross. It’s a blurring of the online and the offline, and I don’t always get away with that successfully. That’s one of those pieces where I thought, Everything I want to say is in this piece.

It’s similar to the t-shirt you’ve made that says “Lamps in Video Games Use Real Electricity,” which draws attention to the relationship between online and offline, too.

I remember seeing that meme and thinking, I’m not into printing memes on clothes. I see memes like it’s someone’s original work. The night before the show, I was fed up and thought, let’s put that on a tee-shirt. It was an important statement to put in front of a fashion crowd in particular. The people who come to my shows aren’t the people who know the video game memes.

It makes me think of how I opened my second show with a knitted mocap suit. It’s one of my knit balaclavas, but it’s got these felt balls. The idea of someone mistaking a mocap suit for a look asks if digital fashion would replace the runway. I was onto something because fashion had to become digital for the last five months. To open a show with that suit and just say, Y’all ain’t shit, this could change at any time… and it did.

How do you generally go about your research process? How do you come across these precise historical moments and decide to create a look or line around them?

That first show was Autumn/Winter 19, and it was the 50th anniversary of Altamont—the disaster festival that ended the swinging 60s. The impetus for that collection wasn’t videogame-y at all; it was thinking about the grander narrative of the failures of free love, environmental catastrophes, and the hypocrisy of Americana. What would that look like through my British eye?

The initiative I was with, Fashion East, gives you three shows. So I thought, Let’s do past, present, future. For the second show, I read about Jessi Slaughter, which is more in line with contemporary ideas of virtuality and digitality. I was thinking about video game girls and the men who played with them behind the screen for that collection.

For the final show, I thought, we’re going to do the future, it should be a remake of the Maul. So already, it’s this meta thing. In the West, the mall is seen as the end spot for the horror movie. It’s full of canned goods and ammunition (and that’s why it makes it such a great video game location!). It’s shelves of ammo, health packs, and medical kits. I was also thinking about the iconic zombie flicks of George. Those three shows are this little ‘American Trilogy,’ I call it. As I was making it, it became my own language, and those references manifested into a coherent idea.

I’m being antagonistic by saying to the fashion crowd that these things mean something. It was a big commentary on contemporary Americana, but also when I’m showing a forest fire on the runway, it means something to the industry. It says that we’re using up the earth in a way we can’t keep up with. There are so many layers to it.

One of Gareth's knitted jumpers, posted to the artist's Instagram page.

Can you talk about how working in Unity has shaped your process? What are the greatest challenges in the engine?

I made headpieces out of Cheetos. When you’re making stuff with a video game engine, and you drag the wrong texture to the wrong object, you accidentally re-materialize the material. An armchair texture becomes a big Cheeto or something. I thought, It’s that glitch in the matrix that tells you that something is wrong. I make bonsai trees out of Cheetos, or a whole cardigan covered in guitar plectrums or jingle bells. It was this idea of these really straight-faced objects going down the runway in a corrupt way. Like, this file’s incorrect.

There’s nothing more tasteful than black trousers and a cardigan with a little bow tie. But then the cardigan is encrusted in kawaii, girly hair clips. To me, the original material is lost in translation—that’s the phrase that I’ve landed on now. The second something goes viral on Twitter, the initial intention is out the window, people have already made up their mind about it. They know what they want to say about it to a fault. I hate that, but that’s the world—you put something in the framework of the runway, it takes on its different meaning.

I was into the idea of showing on a runway because it frames the pieces in a certain way. Ultimately, I want to show clothes as a video game—that is the future of fashion communication—but I wanted to put it on the runway first to show just how much it doesn’t want to be there. I’m fighting back.

How does casting models for a tangible runway show compare to building an avatar or model online?

I work with casting people who have good eyes—they can actually get people to arrive for the show on time, and that’s good enough for me [laughs]. Within that, a lot of the models in my shows are art and fashion students, just kids. My friends have told me that my models look like me, which is funny, but it is true. It’s almost that narcissism thing, of you projecting yourself on your model. The way that I send looks down the runway is how I dress anyway.

The childhood game I grew up with was The Sims 2–it’s the perfect game to me. Casting [in the real world] feels like you’re playing The Sims—you’re playing dress-up, and you’re creating characters. Each runway look is a little story within it. The second show we had, the Sailor Moon look, is the classic trope of video games. The idea was combining these little virtual girls [the garment] and then the seedy boys [the models] playing with them.

When I’m making a virtual model wearing a virtual garment, it’s like puppeteering. It’s the current huge thing happening within the fashion industry of talking about treating models with respect—asking for consent for them to wear certain looks. You know, Can I fix your bra? You don’t have that when you’re dealing with a virtual avatar model, which is weird. You lose touch with reality. I remember it falling into a dark place when I was making The Maul—it became that cliche of the artist with his doll’s house. It’s a pure manifestation of someone’s vision that’s not altered by the circumstance of things. When it’s me making a virtual environment, it’s a hundred percent my vision… sometimes I think no one man should have all that power [laughs]. It’s easy to get lost in it.

Showing with real models brings you back down to earth. These people are bringing them themselves to your world, and I find it incredibly humbling. Also, you have to pay real models—so suddenly, you’re down on the ground when your free virtual avatar doesn’t take a day rate today.

How do you see the relationship between making work digitally and with your hands?

I’m incredibly tangible and hands-on. For all my digital work, I have to print out, cut up, and stick it in a book. If I can’t see it, if it’s not in my periphery—if it’s in a folder on a desktop—it doesn’t exist to me, it escapes me. I’m very much notes, sketchbook; hands-on. My desktop is the messiest thing, but I think that adds to my work.

My work looks like the work of someone that has poor organizational skills [laughs]. It looks like all my open tabs on the browser— a clusterfuck of reference after reference—disparate ideas, no linearity at all, just like the web. I have massive respect for these designers that do a whole collection in one color or one fabric, and it’s a collection. That’s why I’m hesitant to call myself a designer. It’s not a collection. It’s this abundance—a thrift store—of objects.

That’s the only way I can talk about contemporary issues because everything goes now. You can dress up as a goth one day, and then you dress up like a cyberpunk kid the next—there’s no one style anymore. That’s what my work is about. It’s a style-surfing of the 2010s.

What happens to all the tangible garments that you make that are meant to just be shown online?

They are all in a big wardrobe, and sometimes they get called in for photoshoots. I love it when celebrities wear them. It’s like pop art. Tim Walker just shot Dua Lipa wearing my cap full of ice cream. She looks like a video game avatar wearing it.

Much of your work is viewed online through social media or videos. How do you think about your different audiences? How has the reception been on social media versus the fashion world?

It’s so different. My tangible shows are part of Fashion East. That’s the show at London fashion week where they give kids a small budget, and you put on a show, and the world’s fashion press comes to it. These are people that go to 80 shows in a month. They see the same things—the same clothes walking down the runway, the same models. So I tried to use my shows to do none of that, like a cut the crap spectacle within those confines.

We closed A Day At The Maul with a model covered in ketchup and mustard. It’s cheesy gory, but it’s also warpaint. But it doesn’t actually mean anything—it’s the model-as-hotdog as a thesis. So the fashion audience is going to love you for trying, and they’re going to tell you to get the fuck out of here and never show your face again. [My work] lends itself better to social media. That audience can’t get into the show because they don’t have the credentials, and not everyone can get to London.

I’m terrible at social media. I like making physical works, I valued them way more than Instagram. I need to work on that because, for someone obsessed with digitality, I’m scared of it. Maybe it’s because I respect it so much.

Even on platforms like Instagram or Twitter, which are meant to be neutral or non-hierarchical, there’s still algorithms or a grid, for example. Those are still structures you have to work around.

All I want is to make these little video games, but it’s hard to share it with people. There is no Instagram for gaming. I end up sharing a video of a game, and I’m like, I don’t want to do that because it’s now you’ve ruined it… now you’ve made it linear. The whole point is that you’re bringing your audience in, and you’re making them complicit. They’re participating in it.

Maybe the next generation of technology will make that possible. All I want is an Instagram for gaming where I can share these little interactive moments with an audience, and it’s not rendered into a file. I did this commission for this online store Browns in June, and I made a pixel art video called After the Goldrush. But it’s a video, not a video game. My struggle with that was like, I just want this to be a game.

You’re expanding The Maul into a more developed e-commerce platform for the web. Could you talk more about that?

I’m excited to relaunch the Maul—to apply everything that I’ve learned in the last four years to it. It will exist within the browser—it’s vital that it’s no longer a downloadable object for the desktop. At the same time, I understand that technical limitations will inspire what makes the project good. Of course, so much of my audience interacts with my work through mobile. You click the link on Instagram, and it takes you to the mobile website, and that’s another limitation. You can’t have that video game experience on mobile Safari in that way. But I’ve got the content there, I’ve got a body of clothes that I want to share.

The act of selling is also the piece. It’s not the clothes, it’s The Maul! It’s this cursed online shop; fashion’s worst nightmare, chaotic. A big inspiration point for the relaunch is that every online shop has these white backgrounds. It is the gallery wall of our time. How can I play with that image? How can I make my online shop this horrible space that’s half-flooded and with a sparking vending machine?

I’m a fine artist more than anything. It takes talent to design clothes, you know—I knit and make offensive t-shirts [laughs]. I just respect designers too much to call myself a designer. I know what I want the Maul to be like, it’s making it happen is hard because I am so self-taught. I stop and think, What if I studied video game design? What would I be doing? What if I studied knitwear—would I be making a better caliber of product? But I realize every choice that I’ve made has added up into this body of work.

There’s something exciting about being neither here nor there.

My work is corrupted, it’s wrong, it doesn’t fit. It’s not compliant and refuses to participate in the bullshit. The more I add to it, the more it makes sense.

At the same time, I should relish the fact that I actually don’t know what the hell I’m doing. I should lean into the fact that The Maul is this horrible video game, an online store that doesn’t run on any device and will blow up your computer. Once, I was showing the Maul at a university. I ran it on a Macbook Air, and it totally gave the computer asthma. It was running so hot! And then the whole presentation just shut down. I thought, Maybe that’s the point…that’s just the most inept online store you could ever imagine.

“Once, I was showing the Maul at a university. I ran it on a Macbook Air, and it totally gave the computer asthma. It was running so hot! And then the whole presentation just shut down. I thought, maybe that’s the point.”

Where do you see the fashion world headed in terms of virtuality or digitality?

I’ve learned through these concrete runway shows that I’m obsessed with virtuality, but virtuality has nothing to do with digitality. The definition is in essence, but not in actuality. You can’t buy anything because the Maul was not open. It’s just an idea in a moment in time.

Fashion is inherently virtual. On online stores, they’ll bulldog clip a dress tighter to the model, and then they forget to Photoshop it out. So the models are posing with these bulldog clips down their backs. The dress doesn’t fit that way, but they want you to think it fits that way. On my 3D models in The Maul, I’m still going to render virtual bulldog clips on them. It should be this perpetual banter between physical and digital. I like the idea of the CGI garment that doesn’t fit properly.

The Maul should be the worst online shop every step of the way. It’s like buying a pair of stonewashed jeans with holes in them that are brand new, but they’re meant to look worn. The more you pull at the threads, the whole world of fashion unravels. It all comes back to this idea of virtuality.

Credits

Interview conducted in October 2020. Edited and condensed for clarity.