Getting mad at videogames

This article was written by Grayson Davis and originally published on Video Game Heart. For more of Grayson’s writing, you can check out the site and follow him on Twitter.

It was brought to us by our friends at Critical Distance, who find the best in critical writing about games each week. You can see more at their site, and support them on Patreon.

///

As I write this, I am extremely salty. I’m coming down from a series of embarrassing fighting game losses against anonymous online players. I watched from an almost out-of-body perspective as my fingers pressed buttons that my brain was screaming not to. My interior monologue was a repeating crescendo of “Why did I do that?” I’m mad at myself for bad decisions, for missed inputs, for realizing what I should have done and for some reason being completely unable to have done so. This is a self-evidently juvenile frustration—getting mad about video games, of all things!—which only makes it worse. My hands are shaking a little. I am not proud of myself right now.

it is an anger equal parts righteous and pathetic

“Salty,” as in angry, predates videogames by decades, but video games have claimed it as their own. The frustration of the struggling video game player is a unique phenomenon; it is an anger equal parts righteous and pathetic, a whimpering fury from someone very mad about something that doesn’t matter. The measure of how angry you are at performing badly, salt is key to understanding the culture of competitive videogames. For the audience, salt can be an emotional shift in the competition or the impetus of an amusing tantrum—part of the narrative. For the players, salt is a mental liability to avoid yourself or engender in your opponent—part of the game.

Most people who play videogames have witnessed salt even in casual competition. One player begins to mutter about incredible luck and cheap strategies, to audibly sigh after every setback, to look down at their controller as if something must be wrong here. At their peak, the salty player launches into lengthy tirades, explaining why they should be winning and everybody else should be losing. These complaints are hard to take seriously in actual competitive games, and they are obviously overblown in games like Mario Party. Salt is not mere frustration; emotional investment is part of the pleasure of competitive gaming. Salt is achieved at the point where that frustration irrevocably affects how you play.

More than myself, I am mad at my opponents. I’m mad at them not just for winning, but for winning with flawed, predictable, exploitable strategies. I’m mad at them for leaving the game right before I would have won—which, of course, was definitely the next match. I want to shout at them, “If I were slightly better at this game, you would have been obliterated.” I want them to understand in their bones that they did not deserve to win and that, in the balance of the universe, their victories are profoundly unjust. The center no longer holds. Yin now outweighs yang. We are talking cosmic bullshit.

Videogames are rarely that difficult. One does not need superhuman reflexes to mash buttons in Mario Party. If you practice a fighting game enough, the motions become mechanical. A few laps in a casual racing game is usually sufficient to understand the track. Even in games requiring high skill, the people you play with are rarely that much better than you. They are your friends or family or teammates, people you play with all the time.

You make decisions that are bad in theory and bad in practice

The question running through the salty mind is “how?” How am I playing this badly? How am I losing so much? How am I losing to him? The problem feels almost existential. Combos you executed in training mode mysteriously stop working. You find yourself blundering through turns on courses that never give you trouble. You make decisions that are bad in theory and bad in practice and you somehow screw them up even worse.

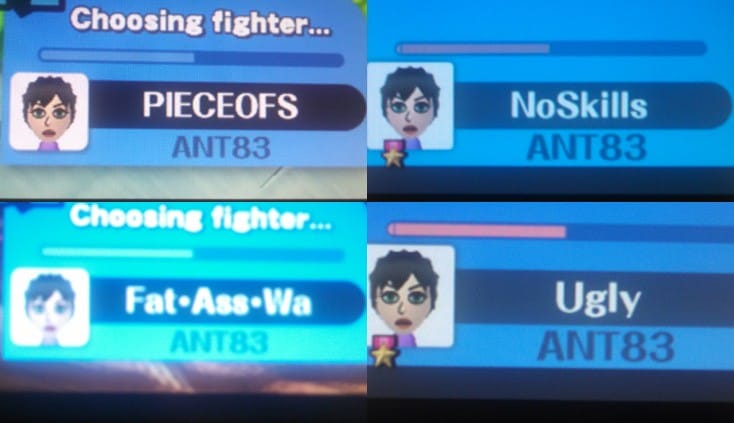

Commentators of fighting games will often remark on the mental state of the players. Although the characters they control don’t express emotion, players communicate a breadth of feeling through their actions: calm, nervous, excited, frustrated, angry, salty. Salty players insist on bad strategies. They continue making the same mistakes in the irrational belief that the justice of the universe will transform their impending loss into a deserving win. Sometimes you win a round and can sense, even through the impersonal veil of online play, that you made the other player mad as hell. Play enough Street Fighter online and you’ll receive a private message telling you to go fuck yourself. You can almost always feel these messages coming.

The driving thesis of salt is not “I should have won” nor “you should have lost.” To be salty is to believe that there is a “should” at all, that competition has a moral arc with a rightful conclusion. Competition is just a thing that happens—more often than not, a thing of no particular significance. Deep down, we all know this. Right now, I’m angry that my cartoon fighter failed to knock another cartoon fighter off the screen.

One match from a 2013 fighting game tournament perfectly summarizes the problem of salt and the plateau it can represent. FSP, a talented Street Fighter IV player, squared off against a random competitor named, in a delightful irony, Gandhi. Gandhi played in a spectacularly terrible fashion, making random, sometimes bizarre choices. He played the game at an astoundingly low level for someone attending a major tournament. Against most competitors, Gandhi would have been a quick and perhaps amusing speed bump along the tournament path. The tournament commentators thought as much and couldn’t contain their laughter.

As the match progresses, FSP falls victim to increasingly ridiculous attacks. He makes and repeats obvious mistakes. He isn’t playing badly, exactly. The problem is that FSP is trying to play well, but Gandhi doesn’t behave like any rational player. You beat such players by playing patiently and defensively, two qualities compromised by frustration. FSP is visibly upset on stream, but you hardly need to see his face to recognize his anger. The commentators state that he shouldn’t lose, but that doesn’t change the fact that he does.

Salt is why good players lose to bad players and why good players stop getting better. Casual players decide, quite reasonably, that a video game played for fun should not make them angry. Hardcore players dig in their heels and insist their losses are the game’s fault or the opponent’s fault or anybody’s fault besides their own. These players probably are skilled when playing at their peak. Inside the hypothetical “if I hadn’t screwed up” tournaments of their mind, they’re great. But while they’re winning in their imagination, other players are winning in the real world, including players who are far worse.

One of the most obnoxious memes in competitive gaming is to tell a struggling player to “git gud.” This sentiment often reflects the self-righteous hostility that makes gamer culture so unpalatable, and many players with legitimate frustrations have been rebuffed by some poorly photoshopped picture. But, at its core, getting good is the inescapable answer to the problem of being bad. Salt is infuriating but it’s not inevitable; it’s a self-serving mindset that offers up every possible reason for failure except “because I’m not good enough.” And usually—as frustrating as it is and as little as it matters—you’re just not good enough. It’s easier said than done to get better, but the first step is admitting you have to.

///

This article was written by Grayson Davis and originally published on Videogameheart. For more of Grayson’s writing, you can check out the site and follow him on Twitter.

It was brought to us by our friends at Critical Distance, who find the best in critical writing about games each week. You can see more at their site, and support them on Patreon.