Glue Gun

Mario delivers a deadly left hook to Solid Snake; Snake falls unconscious, and the citizens of Animal Crossing roar with applause. The Super Smash Bros. series—and other brawlers like Marvel vs. Capcom, Street fighter X Tekken, and Square Enix titles such as Kingdom Hearts and Final Fantasy Dissidia—relies on the collision of crossover characters for its appeal. Videogame crossovers have been around for several years, but they remain indebted to a long tradition of collage.

Collage has its origins in 200 BCE with the invention of paper in China and 10th-century Japan, when pieces of paper were cut and pasted to decorate haikus, a type of poetry that often juxtaposes two ideas or images. The revolutionary sense of collage doesn’t come into prominence until 1912 with Georges Barque’s Fruit Dish and Glass. Braque, who worked in the same building as Pablo Picasso, purchased prefabricated wood grain and attached it to his drawings. Inspired by Barque, Picasso began using pre-existing materials in his work, dubbing it synthetic cubism. Just about anything became fair game for collages: rope, clippings from newspapers, sheets of music. No longer did artists have to create from scratch—they could choose from a catalogue of readymade materials to create new experiences.

Take a look at the more recent collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (1956) by Richard Hamilton, and we can see the advantage of collage: An image of the moon replaces the ceiling; a man appears holding a tennis racket-sized lollipop. Hamilton uses the cover of a Romantic comic as a painting on the back wall, and a collection of other advertisements creates an entirely new room using material from various magazines. Although each clipping comes from a unique source, each has its own embedded meaning that collides with the others in the image. Much like in the videogames I mentioned above, each clip is a character with its own background. Taken out of its original context, the character brings part of its history into the new work, juxtaposing characters, narratives, game mechanics, and aesthetics.

In the Kingdom Hearts series, Disney fans will recognize the oddness of innocent Disney characters teaming up with the often sexually charged Square Enix characters. There is a collision of innocence and sexuality here—of the simultaneous childhood and teenage nostalgia that comes with watching Disney and playing Final Fantasy.

Even mechanics can be cut out of one game and pasted into another. While lost in an illusionary maze in Baten Kaitos (2003) you have to play through a vintage level of maze-based The Tower of Druaga (1984). Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune (2007) combines the mechanics of platformer, shooter, and cinema. You are supposed to be playing an action movie. It’s a collage of game mechanics that sometimes work together, but other times stand completely separate—like when you get into a car in a game where driving was a foreign concept.

The Malygos encounter in World of Warcraft similarly disorients you. To control their character, players memorize a specific pattern of buttons, called a rotation. But in the last phase of the Malygos fight, players encounter a different set of controls for the vehicle (a dragon) they must commandeer. The vehicle comes from daily quests and Oculus—the unpopular five-person dungeon—into the context of a 10- and 25-person raid. This is where groups often fail, because they can’t seem to control this rogue mechanism. There’s a moment of disorientation when a game presents a new but recognizable element in a different venue.

Just what is it that makes today’s videogames so different, so appealing? Videogames are building on the tradition of collage. Like the artists before them, developers have started creating new experiences from the systems and characters we already love.

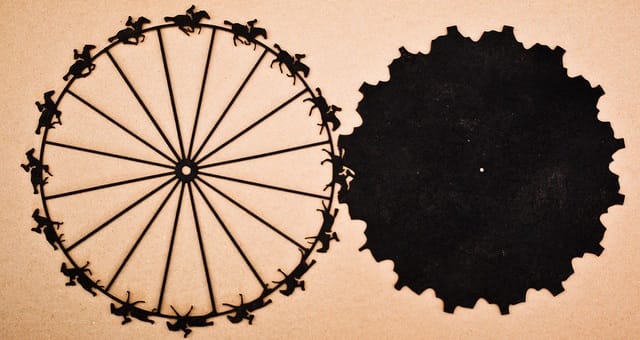

Image: Hannah Höch