The Goat, the Devil, and DOOM

The first time Black Phillip, a perfectly normal-looking goat, appears in Robert Eggers’ 2015 horror film The Witch, the viewer is struck with a sense of unease. This isn’t any fault of Phillip’s. If anything, he should be the most reassuring aspect inthe gloomy story of a 17th century family’s exile to the New England wilderness. Within an atmosphere of dread and fear, Phillip all but mugs for the camera in every one of his scenes. He gives his shaggy head a puzzled cock in the middle of a somber barnyard tableau with perfect comedic timing. He rears up to waggle his stumpy front legs in a funny little dance as twin children call his name. Despite everything he does to counter it, though, Black Phillip remains a menacing figure. His horizontal pupils, great curved horns, and matted beard, lingered on by the film’s camera, form a knot of unconscious concern. He’s a goat, and goats can be disturbing.

///

id Software’s 2016 iteration of DOOM is full of monsters. The player, assuming the role of the semi-mythological Doom Marine, works to beat back the forces of hell spilling into a sci-fi Martian research base. Zombie-like creatures shamble through the opening moments—fleshy training wheels whose fumbling movements and crumbling bodies ease the player into the game’s combat systems—but are soon overwhelmed by a more threatening group of demons.

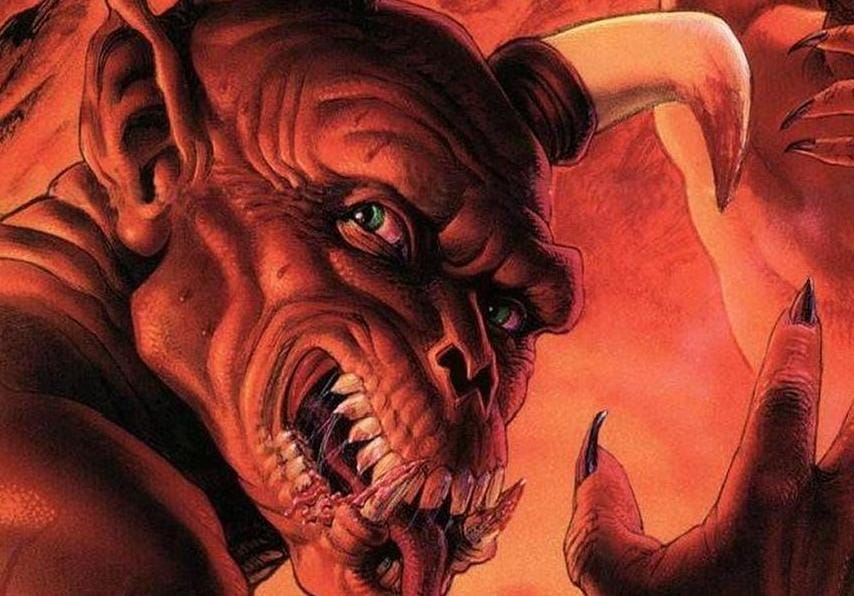

Goat physiology is spread throughout DOOM’s enemy design. Taking its cues from the 1993 original, id blends goatish features directly with human figures (the minotaur-like Baron of Hell and the hulking, massively horned Cyberdemon) or has its characteristic eyes, horns, hooves, and legs incorporated into flying skulls, musclebound “Pinky” demons, and floating, spiky Cacodemons. Though more insectile than mammal now, the fire-throwing Imp, first depicted on the 1993 DOOM’s cover as a smirking, horned beast-man with tongue lolling out between pointed fangs, retains a goat’s springy movements and short, muscular legs.

Each of the game’s demons look as discomforting as expected. Their bodies are warped versions of human and animal—a perversion of nature that recalls the 19th century occult illustrations of Jacques Albin Simon Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal (1818) and Eliphas Lévi’s Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie (published in two volumes in 1854 and 1856). The creatures, like the haunting sketches lining the pages of European demonology and black magic books, unsettle the audience by hearkening back to imagery designed to prod at the nerve centers of a Western cultural tradition whose fears revolve, naturally, around its dominant religions.

///

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when the goat became associated with evil, but a likely source is the Torah and Old Testament’s Book of Leviticus. In detailing the ritual behavior provided to the Israelites from God, Leviticus’ text introduces the concept of the scapegoat—a literal goat, metaphorically burdened with a community’s sins, sent away to die in the desert. The practice (thought to be fairly common in ancient Near Eastern societies) stems specifically from verses in Leviticus in which Aaron is instructed to “cast lots over . . . two goats, one lot for the Lord and the other lot for Azazel. And Aaron shall present the goat on which the lot fell for the Lord and use it as a sin offering . . . (Leviticus 16:8-9).”

The importance of “Azazel” in this verse has splintered theological interpretation. Some take the word as a compounded term meaning “complete removal” while others consider it the proper name of a fallen angel (who is again referenced in the apocryphal Book of Enoch as the first teacher of human vanity and weapon-making). In either case, the goat chosen not to be sacrificed, but cast out, is decided by supernatural chance. And, regardless of exact interpretation, the end result is the same: the goat, through no fault of its own, becomes an embodiment of sinfulness.

a literal goat, metaphorically burdened with a community’s sins

///

DOOM 2016’s easiest difficulty level is represented by a small human skull in a military helmet. As the player moves it up to the highest challenge setting, the human skull progressively morphs into a goat’s. The hardest setting—“Ultra-Nightmare”—is a mutation of the previous level’s straightforward goat skull, the nubs of bone near its temple jutting out into larger horns. The implication is that tougher gameplay—increasingly vicious demons, better equipped to rip the player apart in more frequent death scenes—equates to the game’s evil enemies growing in power.

This is a suggestion DOOM makes again and again throughout its levels. As the story requires the Doom Marine to travel from the corridors and laboratories of the moon base to the bowels of hell itself, the difficulty is raised proportionally—a natural coupling of gameplay challenge and narrative progression that echoes the structure of the first DOOM.

Hell is the demon’s home, and the Marine’s incursions bring both swarms of fearsome monsters and a change in visual design denoting a departure from the human world. When the player first steps through one of the game’s hell portals, she finds herself in a landscape of jagged cliffs spiraling down to stone pits ringed with spikes and patrolled by snarling beasts. The sky swirls a nauseous ochre and the logic of human architecture is distorted. The only pathways are nonsensical routes navigated by jumping across floating rocks and running the bone-lined corridors of labyrinths.

The most familiar landmarks are twisted stone gates, which are quite regularly emblazoned with glowering busts of goat skulls, eyes staring down at the player in silent menace. In providing reference points from the natural world, id decorates its version of hell with the skeletons we leave behind in death and, to maintain a sense of pervasive dread, the skulls of goats. Even outside of its demonic enemies, DOOM marks the presence of evil with references to the animal.

///

As the New Testament built on the Old, Christian thought further entrenched the association of sinfulness with goats. The Gospel According to Matthew foretells the return of Christ on the Day of Judgment, describing “all the nations . . . gathered before him” (Matthew 25:32) before being separated into two groups. The next verse sees Jesus “. . . put the sheep on His right, and the goats on His left.” (25:33)

To the “sheep” Jesus says: “‘Come, you blessed of My Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.’” (25:34) And, to the “goats”: “‘Leave Me, you cursed ones, into the eternal fire which has been prepared for the devil and his angels.’” (25:41)

Sheep and goats are metaphorically distinct throughout much of the New Testament and nowhere is that clearer than in Matthew’s account of Judgment. The loyal sheep stands in for those who will be saved; the goat, on the other hand, is a stand-in for those who will be sentenced to eternal damnation.

As Christianity ascended to prominence in the 4th century CE Roman Empire, the symbolism of the New Testament became more literally tied to the image of the goat. Hellenist figures, like the forest-dwelling fauns and satyrs—especially Pan/Faunus—were goat-like in appearance, and closely associated with Dionysus/Bacchus, the god of wine and fertility who represented unbound, ecstatic thought, drunkenness, and sexual freedom. The influence of these figures—gods linked to an earthy sensuality opposed to the physical denial of Christianity—would go on to inspire associations with goats and sexuality in neopaganist Europe.

The end point of witch covens—groups of women frequently imagined to retreat into the wilderness, worshiping Satan in the guise of a Pan-like goat—would last to the present day. Francisco Goya’s witch paintings, particularly the 1797-8 Witches’ Sabbath, are striking examples (as is 1797-8’s Witches’ Flight, directly referenced in The Witch’s final scene) of the form taken by the devil. Female sexuality, terrifying and necessary to repress in a staunchly patriarchal time and place, ends up mixing with Satanic worship and a renewed spiritual connection with nature in Western popular culture.

represented unbound, ecstatic thought, drunkenness, and sexual freedom

Combined with the following centuries’ rising interest in occultism, these depictions of goats would entrench the animal as an ominous figure. Throughout the approach to modernity, centuries of Christian thought were repurposed in an era defined by a mixture of rationalist, romanticist, and transcendentalist exploration. The scapegoat of Judeo-Christian scripture found itself a focal point for pagan worship as Pan and occult spirituality as the Eliphas Lévi-drawn Sabbatic Goat and Aleister Crowley-worshiped Baphomet. Its current symbolism as a recurring figurehead for the oppositional practices of Satanists shows its enduring power.

///

The goat is a perfectly nice animal. It’s intelligent, friendly, and, as a cornerstone of human agriculture, has provided us with milk and cheese, mohair to make clothes, and help with clearing land and transporting goods. Just the same, the goat has been historically maligned for long enough that its place in Western popular culture is defined not by affection, but a fear cultivated to the point of instinct.

In The Witch, Black Phillip is, taken on his own terms, adorable and a possible source of comfort in hard times. Viewed by the film’s 17th century Puritans, though, Phillip absorbs centuries of mythological association to become something much more frightening. In DOOM, the goat similarly embodies our fears, the physical characteristics of an unassuming animal used as cultural shorthand to create demons that the player can shoot and rip into piles of gore without a sense of guilt.

In both cases, goats become something far more than animal. They, like the ancient scapegoat, are burdened with metaphysical traits—sin, terror, evil—that humans must find a place for. They become monsters and demons, removed from the natural world to carry the weight of concepts that are often too dark and too difficult for humans to wrestle with on our own.

Header image: San Michele al Pozzo Bianco