Grounds for Play

“Excuse me, but are you photographing your own children?” the woman asks me. She is shrill and outspoken in that way that you can tell she lives on the Upper East Side.

“I’m not photographing anybody’s children. I’m photographing the playground.”

“You’re going to have to leave.” She responds definitively.

“This is for the press,” I explain. “I’ve spoken with the Parks Department and they gave me clearance.”

“Well, my husband is actually an attorney, and he’ll tell you that nobody cares who gave you clearance to be here.”

This continues for a few more minutes. Her voice grows louder and more biting. Finally, her husband arrives. People start glancing over at us. Having managed to draw so much negative attention in the span of 15 minutes in a public park, I give up and start packing my things.

“There are a lot of perverts out there,” she shouts as I walk away.

It’s tempting to see the recent history of New York City completely as a history of crime. Compared to many other modern, densely populated, and highly developed urban centers today, the central question in urban planning and renewal since the 1970s has been how to reduce crime, stabilize neighborhoods, and prevent urban sprawl in New York. All of this acquired a renewed sense of urgency following the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001, but the enthusiastic adoption of the broken windows theory was in place for the city’s mayors, police chiefs, and councilmen long before that.

And the thing is, no matter what complaints people raise against New York City’s problematic views of race, class, and civil liberties, it actually worked. Crime did drop substantially, though nobody really knows why (Scientific American and The New Yorker both recently offered great summaries of the most persuasive arguments). Through aggressive policing of public space, Times Square was transformed from a throng of porno theaters into a tourist hub. Gay bars and bathhouses were vilified as miasmatic cesspools for disease in the 1980s with the rise of the AIDS epidemic, and their windows were mostly shuttered. “Perverts” were driven out of public parks and, presumably, the spaces were made safe for playgrounds.

/ / /

“Sand and water.”

Richard Dattner’s voice crackles over the phone. One of the key figures in New York City’s post-1960 revolution in playground design, Dattner still boasts a quirky insistence when he discusses playgrounds.

“Sand and water,” he repeats.

I’ve asked him what materials he finds most interesting to use when building playgrounds. “Because they are infinitely malleable.”

It’s an image that continues to surface as I speak with designers of some of New York’s largest and most interesting playgrounds of past and present. Building such an unstructured and often abstract space in a dense urban maze often feels like you are literally “carving out a space in the city,” Sonja Johannsen, another preeminent playground designer during the 1980s, tells me—digging a hole and then refilling it with something more pliable and elastic. She echoes Dattner’s sentiment, adding that playgrounds are often the most interesting when they have the least amount of equipment, instead relying on their position in nature.

Hearing them describe their projects leads me to imagine the architect as the unseen hand in Eric Chahi’s god game From Dust. Some invisible yet animate force twists metal and cement as easily as if it were Play-Doh to refashion New York City’s façade of permanence into something new at a whim.

Maybe that’s not entirely fantasy. OK, sure, replace whim with 17 million dollars and five years of construction. But what these designers all have in common is an appreciation for the impermanence of their work. “Playgrounds usually have a shelf life of 10 to 20 years,” Johannsen explains. Materials need to be replaced or new safety regulations are passed, which invariably leads to a major rehauling of a space’s design. “People change things,” she shrugs.

“If I could only do one thing, I would do sand,” Matthew Urbanski tells me across the conference table of the Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates offices in Brooklyn. A principal at MVVA and lead designer of the Brooklyn Bridge Park Pier 6 playground—one of the largest and most expensive ever built in any of the five boroughs—Urbanski says that he hopes creating more malleable spaces might help prevent bullying and youth aggression. Children should be allowed to be alone, be allowed to step away from the aggression and competition of others if they want to.

Sand and water.

/ / /

Scholars of urban space often compare cities to living, breathing organisms. Then what part of this giant urban body is the playground? “Play” can seem like an effusive concept for urban planners compared to the overwhelming intricacies of, say, building the new subway line that’s supposed to be in the Upper East Side eventually (knock on wood). But modern playgrounds have their own contentious history as a New York fixture.

Mathias Crawford suggested in our Public Play issue that “playgrounds may be entering a new golden age.” As concerns with public safety decrease alongside the drop in criminal activity in parts of New York, a powerful upsurge in popular science and culture is recognizing the psychological benefits of unstructured time and activity in children’s lives. This lends play spaces a new seat at the table. As Dattner puts it: “There are a lot of young parents who are very concerned about their kids’ future and making sure they get to the right nursery school so they have a chance to get into Harvard. So suddenly they’re rediscovering play; it’s hot again.”

The history of playgrounds in New York City is as long and winding as anything else in the city (for a more definitive explanation, read Susan Solomon’s history American Playgrounds), but Dattner explains it like this: There was an upsurge in public interest from the 1930s to the 1960s, followed by a steep decline throughout the 1970s and ’80s when playground design largely stagnated, until interest renewed a little over a decade ago. When he began his career as an architect in the 1960s, a playground in New York City was usually “a sea of asphalt with discreet elements mostly made out of steel pipe—swings, see-saws, slides—on a dangerous hard concrete paving.” It’s easy for anyone who’s skinned their knees on much less treacherous surfaces to imagine the problems with this type of environment. Along with the landscape architect M. Paul Friedberg, Dattner was inspired by a playground project designed by famed architects Louis I. Khan and Isamu Noguchi. Adventure Playground became the first of five sprawling and inventive spaces Dattner designed for Central Park that still exist in some form today.

Children were given “real hammers, real nails, an outdoor fire,” he continues, “and they were surrounded by a lot of nature.”

As an artist, Noguchi was always staggering in its inventiveness and ambition—a trait that unfortunately made his work seem too complicated and untenable when it came to playgrounds, which were thought of in very functional terms when he attempted his designs in the 1930s. One recent article in the New York Observer describes his most famous structure, Play Mountain, as an intellectual challenge to the children who would play in it: the structure “would have filled a full city block with a pool, gymnasium, skating facilities and playground in the shape of a gently sloping, tiered pyramid housing a usable interior space.” Standard equipment, meanwhile, was “eschewed in favor of sculpting the earth into abstract mounds and peaks.”

In American Playgrounds, Susan Solomon describes the envisioned space as having the potential to “force its users to discover new activities, things that they had not been able to verbalize but that would emerge from confrontation with the structure.” The inspiration for this new vision of children’s play dates back to the German occupation of Denmark during World War II, when the Danish landscape architect C. Th. Sørensen noticed how children were using the detritus of wartime to build their own worlds for play. As Robin Moore of the Natural Learning Initiative explains it to me, architects started to notice that “kids had more fun with the playground when it was under construction” than when it was actually completed.

Its transition to America, however, wasn’t a simple transplant. Noguchi’s original concepts were rejected. By the time Dattner and Friedberg began building their Adventure Playground, Moore explains, the original concept of “adventure playgrounds” was diluted down to the label alone. “The originals were very child-focused,” he explains. The spaces were generally enclosed and supervised by adult employees called “play workers” or “play leaders.” This not only took the stress off individual parents to hover anxiously over their children, it encouraged children to take bigger risks and engage in large, loosely structured group activities. Children were given “real hammers, real nails, an outdoor fire,” he continues, “and they were surrounded by a lot of nature.” Using sharp objects around open flames, Dattner recalls, is something that American communities wouldn’t stand for.

Children in adventure playgrounds, in other words, were “creating their own community” by participating in it in a number of different ways. And what was more, their actions had tangible consequences—the sort of “variable, quantifiable outcomes” produced through participant effort that videogame scholar Jesper Juul uses in his very definition of a game.

There was a brief moment when something closer to the original vision seemed like it might survive in America. Ultimately, however, many crucial aspects were abandoned. “The play leaders lasted for about five years,” Dattner says. “The local parents would have a fundraiser and raise money to pay for that—because the Parks Department has never had a budget for that role.”

“If you go to some of the older parks around a place like New York City,” Moore says, “you can still see the marks painted on the ground showing where the play leader was supposed to stand and where the children would be grouped.” Slowly but surely, all these spaces were eclipsed.

/ / /

Financial concerns in the 1960s and ’70s led many of the most unique playground projects, such as Dattner and Friedberg’s collaboration, to be abandoned in favor of more permanent and stable structures. Moving parts like swings, ropes, and sand, the element that Robin Moore explained was most crucial to giving children a sense of creativity and interaction to their play, were largely deemed hazardous or flimsy.

More pragmatically than these broad social and historical dilemmas, however, was the rise of litigation against playgrounds in the subsequent decades. Urbanski explains that Americans are the most trigger-happy communities when it comes to lawsuits and liability for any equipment deemed dangerous or risky to children, which makes many playgrounds profoundly risk-averse. MVVA tends to order most of its play equipment from European manufacturers, finding many of the restrictions set by American manufacturers to be too limiting. Solomon echoes this in her book, lamenting the rise of the “McDonald’s model” that established a “cookie cutter approach for design.”

“The whole point of play is that you can fail.”

How do you then innovate in a cramped city where space is such a rare commodity? Today the largest and most interesting playgrounds (many of them designed by Valkenburgh’s firm) are “destination playgrounds”—expansive and majestic spaces, no doubt, but far more removed from urban life than the slides and swings sprinkled throughout Riverside Park. While inspiring, I’m left wondering what communities these are really made for. And then there’s the extremely limited space reserved for most playgrounds. Sonja Johannsen claims, for instance, that the minimum physical distance between the play space and the street needed to meet regulations for a swing set has all but removed them from the majority of play spaces in New York.

“Obviously you can’t completely reinvent a space,” Robin Moore says. “But you can get very close.” The idea for the renovated Teardrop Park—a cascading set of stones surrounding a single, massive slide and punctuated with fountains—was to make “the whole park into a playground.” Wedged tightly between several residential buildings in Battery Park City, the complex machinery of a swing set or carousel was out of the question. Unable to populate the space with such toys, Moore suggests, they instead turned the groundwork into one big toy. Introducing something as simple as vegetation or a community garden does not suggest play as immediately, but does stimulate community responsibility and ownership to ultimately engender a “creative environment.”

This is what strikes me as so essential about playgrounds, and what separates them from the forms of play we find in videogames. Every game is loosely defined by the dynamic formed between the player and their environment—call it a set of well-defined rules in a virtual space, as opposed to the strict physical realities of the natural world. Playgrounds live in a sort of nexus between game and play—they’re not entirely rule-bound systems, but they’re a fundamental location in real life to promoting experimentation and risk-taking. These things are second nature to gamers who dare to, say, climb a mountain in Skyrim, but freak out parents when they see a child tottering dangerously atop an insecure surface.

And that is ultimately the essence of play. “The whole point of play is that you can fail,” Dattner tells me as he airs his frustration for increasingly rigid safety concerns. There is a psychological and developmental element to this type of play, wherein a child thus learns the physical boundaries of their own body and the world around it.

Taken from a social perspective, as it inevitably must be considered in a public space such as a playground, play stands for something much broader: the ability to shape and control one’s environment. In Dattner’s 1969 book Design for Play, for example, he periodically breaks into an impassioned rhetoric remarkably similar to the language invoked in any public protest:

One of the most disturbing aspects of our modern technological society is that it is full of experience and sensory stimuli, but increasingly less under the control of most individuals. The recent riots in the slums of our cities are an expression of ghetto-dwellers’ frustration resulting from their inability to have an effect on their environment. The need to make some mark on the world one lives in is as fundamental as the need for food and shelter, but it is much more difficult to satisfy.

Play, then, is more than just fun. As Anne Frederick of the Hester Street Collaborative tells me, playgrounds and parks are like bars in that they increase civic engagement and social solidarity. The potential benefits go far beyond simply designing a space for play. Slate recently published an excellent series on the “Crisis in American Walking.” Simply put, Americans don’t navigate public space on their own two feet anymore. How will space be reconfigured in the coming years to suit such an atomistic and isolated social order?

Today, the most experimental playground in New York is David Rockwell’s Imagination Playground (which we profiled last October). At first glance, it looks like a very large Lego set, except all the parts are made out of polyethylene foam. Blocks, boxes, slides, and wheeled carts can be used to make ad hoc structures and vehicles. Many of the designers I spoke to were excited at the potential, but wary about its future success. When I asked Robin Moore, he called it a “valiant attempt,” paused for a moment, then added a moment later, “I’m not sure how exactly to apply it, but that’s all I’m going to say.” Frederick was more openly doubtful, saying pointedly at the end of our talk that “rubber blocks are never going to be as compelling” as the shapes they try to emulate.

Adults, however secretly, probably crave these sorts of unstructured play experiences.

The ideal age for playground use ends around 11. Alison Gopnik, a psychologist at U.C. Berkeley, reasons that this is when children begin to embrace and invent rules. You see this during recess, as suddenly everyone starts playing Freeze Tag and Hide and Go Seek. They also begin playing competitive sports around this time. Gopnik theorizes that transitioning into more structured environments, such as school, begins to reflect itself in play—games become more clearly a way to understand and navigate rules. But adults, however secretly, probably crave these sorts of unstructured play experiences—how else can the massive success of such loosely ordered games as Skyrim and Minecraft be understood? Even here the idea of play can be extended.

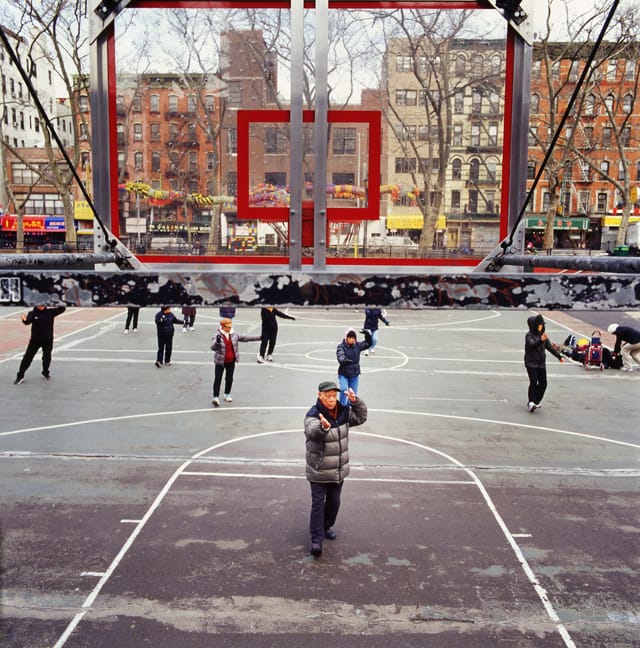

“If you look at something like parkour,” Dattner says, “[you see] adults playing in these same spaces in their own way.” Frederick agrees, adding that the process of designing new areas must itself be playful for a community to truly appreciate them. The ultimate goal is to create a space universal enough that, throughout each day, it’s constantly refilled and repurposed, transformed anew by play. She tells me to observe the Hester Street Playground down in Chinatown. I arrive early one brisk morning to see a group of elderly men and woman practicing tai chi next to the playground. Slow and somber, it’s a warming contrast to their jubilant children that trickle down Chrystie Street as the day goes on.

A few days later I was walking through Tarr Family Playground on the Upper West side of Central Park. A group of parents stood along the edges of the fence, watching as their children wove in and out of the wooden maze leading toward a large stone obelisk and slide. On the other side, two teenagers balanced themselves on opposite ends of a metal railing, leaping back and forth.

“It’s time to go, honey,” one father shouted. His daughter began to cry. The two boys continued their dance as the children faded away.

Watching them continue to perch precariously on the cold, slippery metal of the railing, I thought of the last thing Robin Moore told me when we spoke. Having consulted for so many playgrounds, I wondered, what was his favorite piece of equipment in New York City that was designed solely for play?

“Oh, that’s easy,” he said. “The giant metal dome in Union Square Park.”

“Why?” I ask.

Built by a silo manufacturer, the piece stands in Union Square for its impressive size and joyful irrelevance. Shining the dull silver of brushed metal, every time I pass by I see a child gleaming joyfully, standing proudly at the top. Eighty years later, and New York finally got its play mountain.

“Because,” he responds, and I can hear his voice beaming as well, “There is always a child standing beneath it with no idea what to do—he doesn’t know how to hold it, how to play with it. But he just enjoys it.”

Photographs by Yannick LeJacq