High Scores 2014: 15-6

Header image via Ollie Hoff

///

(Click here to read part one of our Best of 2014 list.)

(You’re currently at part two of our Best of 2014 list.)

(Click here to read part three of our Best of 2014 list.)

(Click here to see the rest of our year-end coverage.)

///

15. This War of Mine

War is hell, and every ounce of This War of Mine is carefully designed to make sure you know it. While managing a group of civilians caught in a massive conflict, players will be faced with scarcity, illness, despair, hopelessness, and choices with powerful consequences. There are no heroes in This War of Mine; only survivors, whose morality is whittled away over time as the survivors become pragmatists, driven by a need to overcome and justifying abhorrent acts in the name of survival. Not everything is grim, however. Beneath the thick layer of desperation, there’s a slice of hope that shines through at random moments—whether it’s a tender encounter between survivors, or the surprise drop of supplies from unknown saviors. From start to finish, This War of Mine is a drastic departure from the power fantasy many war games have become, and this is what makes it so unshakeable.

— Cassidee Moser

14. Shadowrun: Dragonfall

I didn’t truly know Picasso until I saw his lithographs. Behold this wonderful shit! Their economy of form makes you wonder if anything can be perfectly expressed in a few pencil strokes. (Then you look at a Monet and remember that, no, it cannot.) The drawings are arguments for simplicity, a reminder that every literal or figurative brushstroke an artist employs should have intentionality behind it. Else, what are you muddying the canvas for?

Shadowrun: Dragonfall is what it needs to be. It’s a turn-based RPG that foregoes many of the genre’s characteristic excesses. It has no voice-acting, because its gloomy electronic soundtrack and self-consciously literary writing set the mood just fine. Its story is specific and patient. Over time, the world and its characters unspool. The battle system and skill trees are not uncomplicated, but they’re learnable. The game trusts you’ll get the hang of it.

How exhilarating it is, to encounter art that trusts you. You feel like you’ve met a new friend.

— Colin McGowan

13. Alien: Isolation

The aesthetic of Ridley Scott’s Alien will always be something of an anachronism, decidedly moreso now than at its release in 1979. The pixelated screens operators use to interact with the derelict freighter and its automated systems seem almost as alien today as the beast that hunts the crew.

The Creative Assembly latched onto this concept with the grip of a goddamn facehugger for Alien: Isolation. The eerie green glow emanating from retro-future consoles are coldly oppressive. Interfacing with the devices onboard the Sevastopol Station is as clunky and slow as it is nerve-wracking, especially when the xenomorph slithers into the area. Plasma torches, signal jammers, makeshift weapons, and the iconic motion trackers all force the player to confront a future where technology has failed in its utopian promises by turning our dependence on machines into a source of horror and vulnerability. Though this theme isn’t exactly new (even for games), Alien: Isolation’s commitment to retro-future kludge makes every attempt to progress an anxiety-inducing fight against the technology that holds us hostage. The game makes desperate engineers of us all, combing through the wreckage of our own invention and hubris while something even more dangerous stalks us from the shadows.

— David Chandler

12. Sportsfriends

It feels weird to include a compilation on a year-end list, but Sportsfriends isn’t so much a disparate collection of games as it is a singular tribute to joy. In a year that saw games like Nidhogg and Samurai Gunn become favorites, it’s clear that local multiplayer is officially a thing, but Sportsfriends trades directly violent adversity for something far more ridiculous. From the multi-jumping cutie-dunks and adorable attacks of BaraBariBall, to the bastardized pole-vaulting action of Bennett Foddy’s Super Pole Riders, Sportsfriends eschews traditional videogame knowledge and skill for things that are mechanically and aesthetically childlike. They’re not bad or malformed, but pure, simple, and gleeful: tools untouched by the weight of the outside world. A reinvention of a stick and ball.

In the throes of a frantic game of Hokra’s odd sport, or the screen-neglecting spatial arena of Johann Sebastian Joust, all that remain are you, your friends, and your controllers. Each game taps a delight so pure that even losing can feel like winning. As Ramiro Corbetta (developer of Sportsfriends’ Hokra) put it in an interview: “I was trying to basically get people to yell at each other a lot.” Mission accomplished.

— Paul King

11. Threes!

We all learned quite a bit this year because of Threes!. It refreshed and expanded the boundaries of our multiplication tables while also bringing us into a conversation about the intricacies of copyright law and the market impact of so-called “clones.” At its basic level, Threes! is ingenious design—a simple yet profoundly original premise that is fundamentally resonant. Take the basic swipe action of touchscreen interactivity combined with some elementary school math exercises and a dash of spatial awareness and you’ve got the basic idea. Threes! is like one of those old sliding tile puzzles with less complicated maneuvers but a wider possibility space for viable actions. However, the game’s Tetris-like appeal in today’s App Store climate means that a glut of copycats, some more blatant knock-offs than others, have also flooded the market, vying for players’ attention. As a result, Threes!, along with being the progenitor of this new genre, is the artisanal, premium version of the tile-sliding, number-matching game. The jazzy music, goofy sound effects, quirky sense of humor, and punchy visual style lend the experience an actual sense of character on top of its already inventive game design.

— Dan Solberg

10. Bayonetta 2

Who loves Christmas more than Bayonetta 2? It’s not just that the game starts on Christmas Eve and ends with its villain turning from a man-sized snowflake into a golden ornament. No, Bayonetta salutes the holiday by giving us a senseless amount of stuff, burying us under jets and high heels and power armor and chainsaws that you wear like roller blades. We may have killed God in the first game, but not believing in Santa, Bayonetta 2 tells us, is “sacrilege.”

The series has always mixed the sacred and the profane, apparently just to see what that looks like. The gold and stone masks of its divine bosses fall away to reveal raw baby faces and huge lizard eyes. A trail of purple flowers and kisses leads from heaven to hell and up the holy mountain where a god of chaos lives. Someone’s showing off, really: Bayonetta’s combat base is so smooth that Platinum can improvise anything over it. The whole cosmos is there for style’s sake.

Everything in Bayonetta builds from the Verses, the boxed and graded enemy drops that compose every chapter. Platinum’s Metal Gear Rising was a shredfest that asked you to walk into a wall of death, but Bayonetta is about stepping back and opening up space, allowing wild elaborations on a familiar theme. The game’s strength is its flexibility, and it’s showing that off again when it showers you with toys. The Moon of Mahaa-Kalaa lets you counter attacks by flicking the directional stick at them, a trick that recalls (but actually predates) MGR’s parries. The Chain Chomp, one of many baffling Nintendo tie-ins, bites enemies without being told to. And the nastiest rhythm in an action game this year belonged to the spinning Salamandra chainsaws, which buzz back for an extra cut if you release the A button just as their teeth glow red.

Bayonetta 2 is not as long as its predecessor, but it feels more stuffed with ideas. The brakes come off the plot and it barrels through time and space going wherever it wants. I’ve played both games to death, and I am no closer to a unified theory of Bayonetta. I only know that it’s a gift.

— Chris Breault

9. Desert Golfing

I haven’t stopped playing Desert Golfing since it came out. But with few exceptions, I couldn’t really tell you anything specific about it—here was a rock; there was a cactus. After a patch, bottomless holes became filled with water which billowed up into a tiny splash whenever I hit a ball into them. And after more than 3,000 holes and nearly 10,000 strokes, it all blends together: the only thing to do is move forward. Hitting the ball slowly becomes a meditation: touch the screen. Draw back the finger. Desert Golfing finds a middle-ground in the Zen of spacing out somewhere between Angry Birds and archery.

It’s impossible to ignore Desert Golfing’s appeal, even when it perhaps should have none: the mechanics are nothing new. Golf is nothing new. The landscape, while eternal, could also just be boring. But each hit of the tiny white representation of a ball—and its tiny, false, hollow representation of the sound a golf ball makes when struck—is just one more piece of an addicting experience that somehow comes together into something that is greater than the sum of its parts.

All of this makes it easy to dismiss, or even to jokingly (or seriously) refer to it as Normcore, Trollcore, or ____core. I think this speaks to the game less as a game and more as a cultural monument. Chances are I’ll never finish it; chances are you’ll never finish it either. It’ll just sit there on an iPhone, in the same way that Kenneth Goldsmith’s conceptual poems sit on a bookshelf. Both are fully realized by just being; the reader/player engagement is only secondary to their existence.

And yet, here I am. Hole 3315, stroke 10,029. A deep pit separates the ball from the hole, a small crater resting just behind an overhang. The flag is a bright, pointy yellow, and the sky and the hills converge into a deep, saccharine purple. I know they used to be orange. I couldn’t tell you when they changed.

— Paul King

8. Nidhogg

Nidhogg begs to be played in a room full of people. Half of the fun is the screaming and laughing that will ensue, and the other half is the smug satisfaction of watching your opponents try not to throw the controller across the room when they lose. The back and forth of the swordplay becomes hard to watch, but there is always that surge of adrenaline accompanying a particularly hard-fought kill. It’s like watching a tight, well-choreographed dance—except someone dies at the end, and the room laughs and lets out a collective sigh of relief.

It helps that the game is an audio-visual feast. You’re ducked down and hiding in grassy fields as the music picks up pace in the background, waiting for your opponent to run directly into your trap. When you die, your blood stains the level like brightly colored paint, and by the end of a long match, the floors are covered in blues and greens, pinks and yellows, in a gorgeous display of carnage. But even if this rainbow-washes the violence of this game, there’s something nevertheless unsettling about the dominance you feel watching your player rip your opponent’s spine out. Even when you are just tiny, pixelated players, you feel god-like. Normal humans don’t do that kind of stuff. Supernaturally powerful beings do. But even gods get scared. You can take off running towards your finish line as fast as your legs will carry you, but you know your opponent is going to be waiting for you right behind the next door. Right over that next ledge. Crouching in the grass. And they’re a god, too.

— Kelsey Sidwell

7. Mario Kart 8

Mario Kart 8 hit the pavement screeching. If you’d played any Mario Kart prior to this (as most have, it would seem) you had a good idea what to expect here: this was made to order and aimed to please. For myself at least, the hours spent mastering the poetry of drifting or even just cruising for thrills in the previous iterations of this game were not in vain, especially when traversing all these tracks I’ve grown to love and groaned to lose in throughout the history of the franchise.

Nintendo could have stopped there and I’d have been satisfied, if merely. But then there are the elements I didn’t even know I wanted: Anti-gravity sections of every track? On paper I scoffed, but in play they edge this up from a regular race to a competitive roller coaster. Highlight clips? In all honesty, if at first the game itself only had my interest, it was the GIF avalanche of delightful and often chuckle-worthy replays (AKA the now-ubiquitous-for-a-reason “Luigi Death Stare”) that solidified my attention. Toss in more reliable online races amongst friends and strangers alike and I begin to see how a classic can be improved by degree.

But even the familiar elements that been upgraded to match my contemporary sensibilities. The visuals are finally as slick as the controls dialed in from generations of play-testing (and the sloppy motion variant is fun, too). My cherished sport bike now shimmers with a colorful pop that holds tight to the cartoonish thrills and bedeviling physics particular to Mario Kart. The live big band soundtrack swings and shuffles the mood onto “playful” rather than “bloodthirsty competition.” Visible skid marks can be found on later laps, making every course feel lived in. And let’s not forget the old and new playable racers who come in large, medium, and small; the 50-100-150 cc’s of “fuck you blue shell” and other item-based mayhem; and nail-biting ghost-chase time trials.

Mario Kart has defined casual videogame racing for decades by focusing on a good time like blasting a friend’s balloon with a well-timed green shell, a solid whip around that asshole Iggy on a curve, and skirting by a piranha plant that’s nipping at my tailpipe. Here, in its eighth incarnation, this rowdy playable cartoon is executed to near perfection, a churning chaos of participatory spectacle.

— Levi Rubeck

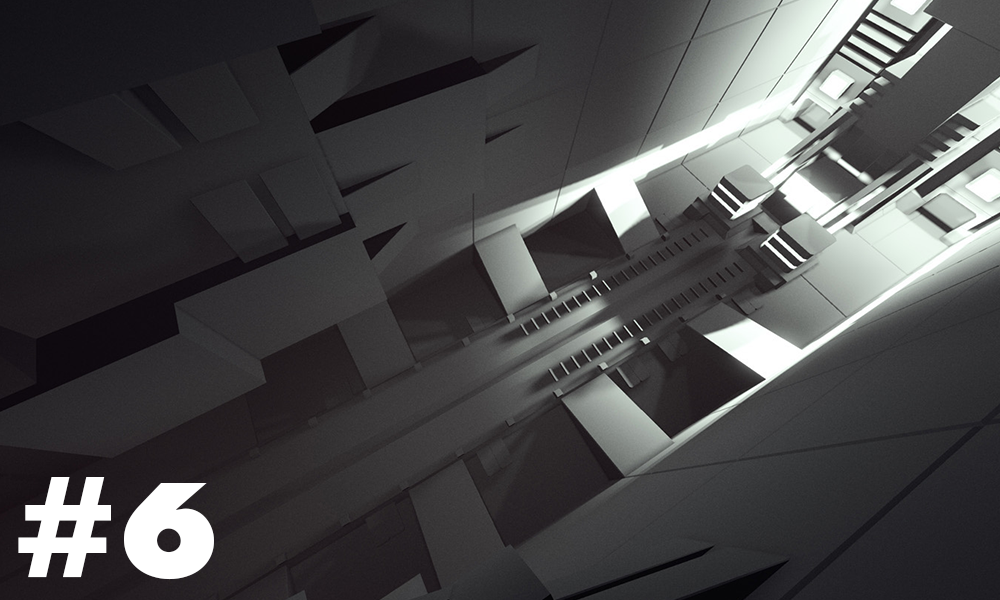

6. NaissancE

At its most basic level, NaissanceE is a conglomeration of stone structures, all pitched at different heights, angles and volumes; all struck with different chords; all connected through blinking transitions into a vast concrete symphony. It asks you only to walk and wonder for the most part. You devour befuddling mists of masonry with only a passing gaze. At times, you jump between stark walls pocked with nameless windows, leap to ziggurats. And, at its impossible depths, you clamber across grand sci-fi metropolises that are both busy with detail and strangely unoccupied.

It is as if you have been let loose within a series of those high-concept design pieces that architects occasionally draw up but are never materialized. Sometimes, orbs of light guide your curiosity through dark mechanical intestines, other times a hulking corridor will dictate your direction towards a shaft so colossal and ungodly complex that you feel as if the universe has opened its gargantuan maw for you to stare nervously into it. It’s a production that manages to be claustrophobic and vertiginous—a dissonant chorus of the infinitesimal and behemothic. The motifs that tie it all together are those of chiaroscuro, brutalism, and a dynamic filmic quality. In short: it is otherworldly and it is huge.

There are puzzles to solve among all of this; wordless as ever, realized as tableau of monolithic entities. And dangerous pipework divulges the game’s biggest mistake: adding frustration to first-person platforming. These set-pieces are needless (and sometimes painful) diversions from the root fascination but, thankfully, are only blips in what is arguably this year’s most beguiling journey. And it’s certainly the most striking debut in videogames of the past 12 months, with Limasse Five delivering a prodigious opus from a position of obscurity, asserting a rare confidence in its complete vision.

— Chris Priestman

///

(Click here to read part one of our Best of 2014 list.)

(You’re currently at part two of our Best of 2014 list.)