High Scores: The Best Videogames of 2015

Header image and artwork by Caty McCarthy

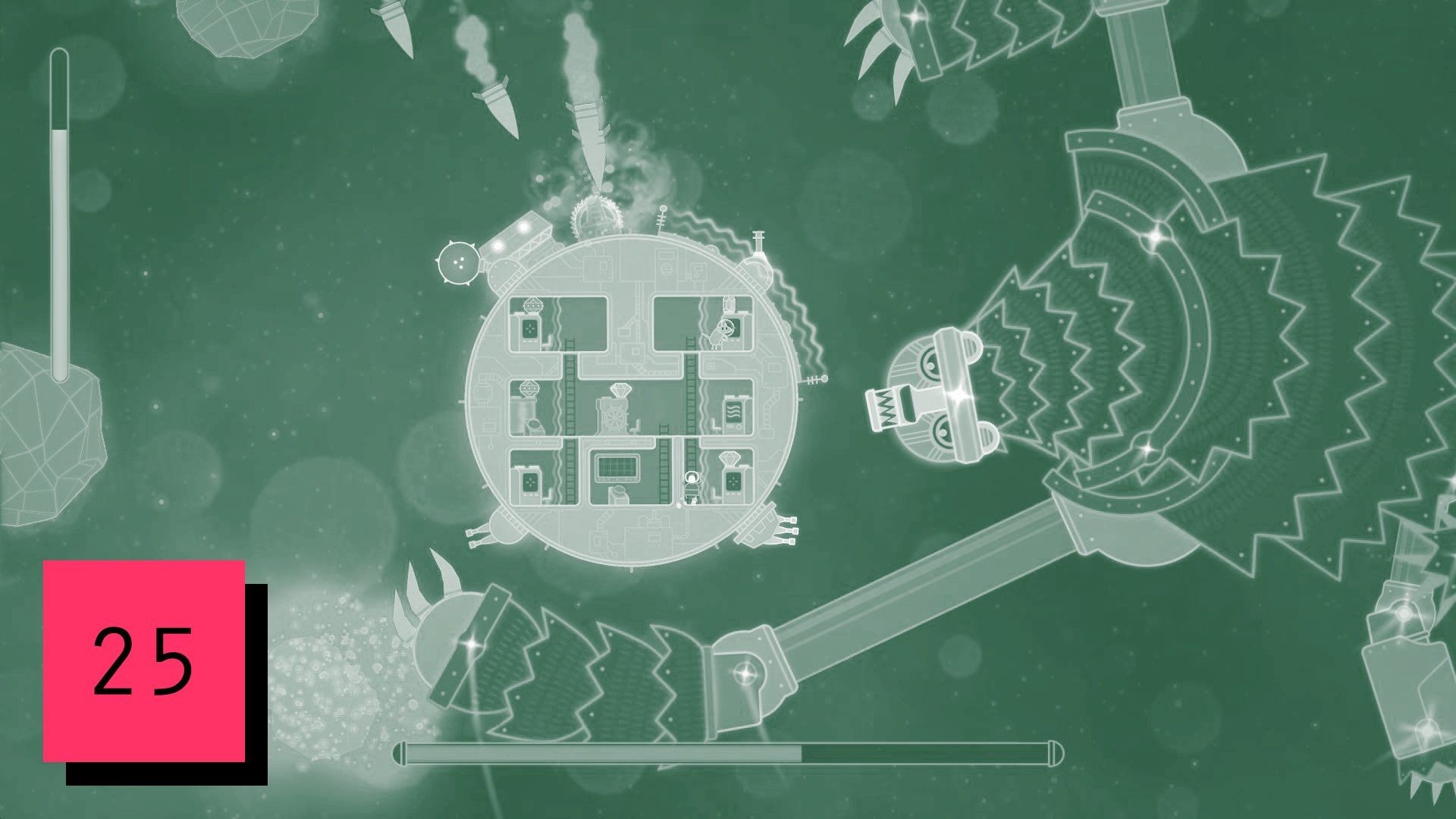

25. Lovers in a Dangerous Spacetime (Asteroid Base)

Neon cuteness belying hardened spacefaring carnage. A manic platformer disguised as a cheerful shoot-em-up. Lovers in a Dangerous Spacetime is a lot of things, and all of those things are descending on you at the exact same time.

With the evil forces of anti-love surrounding you as you save imprisoned space bunnies, Lovers works best with two players sitting side-by-side, working together against near-impossible odds. An AI-controlled dog or cat can accompany you on your suicide mission, but facing down increasing waves of enemies next to your IRL buddy is where the game ramps up into the sublime.

Lovers succeeds in bringing two people together as more than just teammates. Every time I’ve played the game, I’ve had a blast with whoever was helping me out. Whether it was one of my best buddies on the couch or the 12-year-old girl who picked up a controller at Seattle’s EMP game exhibit, we fought bravely, laughing and cheering each other along until the bitter, adorable end. –Davis Cox

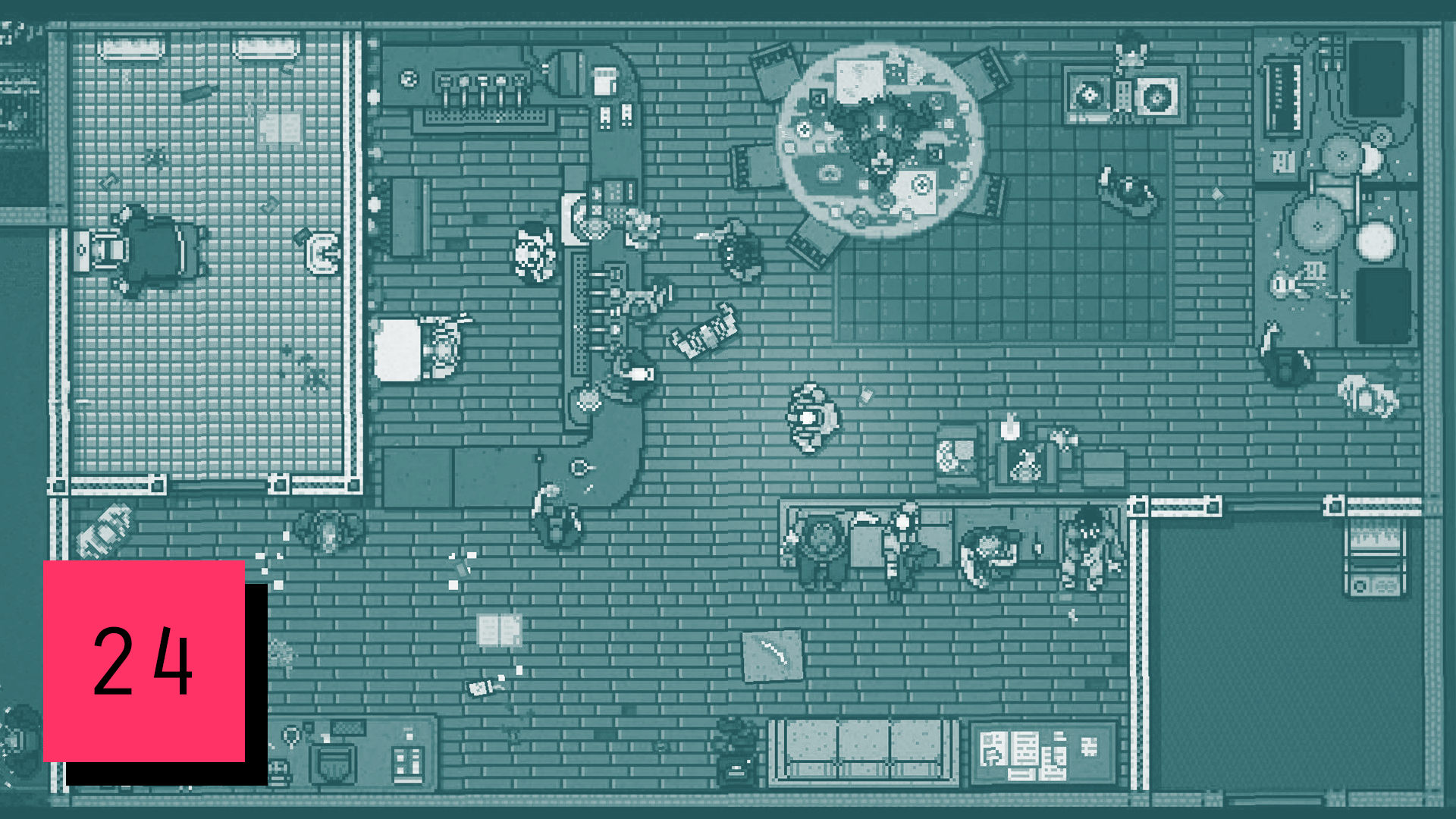

24. Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number (Dennaton Games)

Saturated with blood, Giambattista Marino’s “Massacre of the Innocents” is stanza after stanza of old fashioned 17th-century baby murder. Ripped, gutted, and obliterated in bloody ecstasy, the poem is unrelenting mayhem. I kept thinking of it as I played Hotline Miami 2: Wrong Number, a game of massacres and splattered organs with its own pulsing meter, all in the surreal tradition of its predecessor. The formula is freshened with a spread of intrepid methods for clearing rooms of faceless Russians, etc., though I died probably five times for every single bald mobster I slaughtered. It’s chaos wrapped in neon with a plot that Pynchon would blush at—which is to say, it’s thrilling.

It is also a direct reflection of America’s gun-obsessed culture of violence. But if Congress refuses to fund the CDC’s scientific studies on violence, we must approach that culture through culture, and Hotline Miami 2 holds up a gilded, throbbing mirror. Like “Massacre of the Innocents,” Wrong Number isn’t intended to be taken literally. Some games dissect violence, others mawkishly attempt to glorify it, but Wrong Number is nearly immersion therapy. We confront the monsters within us through cultural works so that we might better understand ourselves, and Wrong Number cranks the gain, paints with bullets and pizzaz, dabbles with inscrutability. It juices the weird feelings we generally avoid in the name of entertainment, and is all the more powerful for doing so. –Levi Rubeck

23. Pillars of Eternity (Obsidian Entertainment)

Anyone making the “nostalgia bait” argument about Pillars of Eternity, the successor-in-everything-but-name to the Baldur’s Gate series, is a cynic. Pillars of Eternity proves, as Divinity: Original Sin did last year, that revisiting older frameworks provides fruitful opportunity to perfect classic videogame styles, while at the same time smooth out the kinks that have made many classics obsolete and sometimes utterly unplayable.

Pillars of Eternity plays it largely by the book, with that familiar overhead angle and tense, pause-heavy combat. Instead of burning down the pantheon to erect something new for its own sake, tweaks were made to push back and improve upon the formula. Hit points weren’t replaced, just augmented with endurance to create a new concept of short-term health versus long-term health. The stats and their interplay don’t tear up the D&D character sheet, but they’re mercifully free of arcane concepts like THAC0.

These changes aren’t statements. They are refinements. The success of Pillars relies on constraint—both the constraint of working within classic models, and the constraint observed in updating the model. Even though it invokes the games we loved as kids, Pillars doesn’t need players to equip their Rose-Colored Glasses of Halcyon Days. It wants you to look forward. –Darren Davis

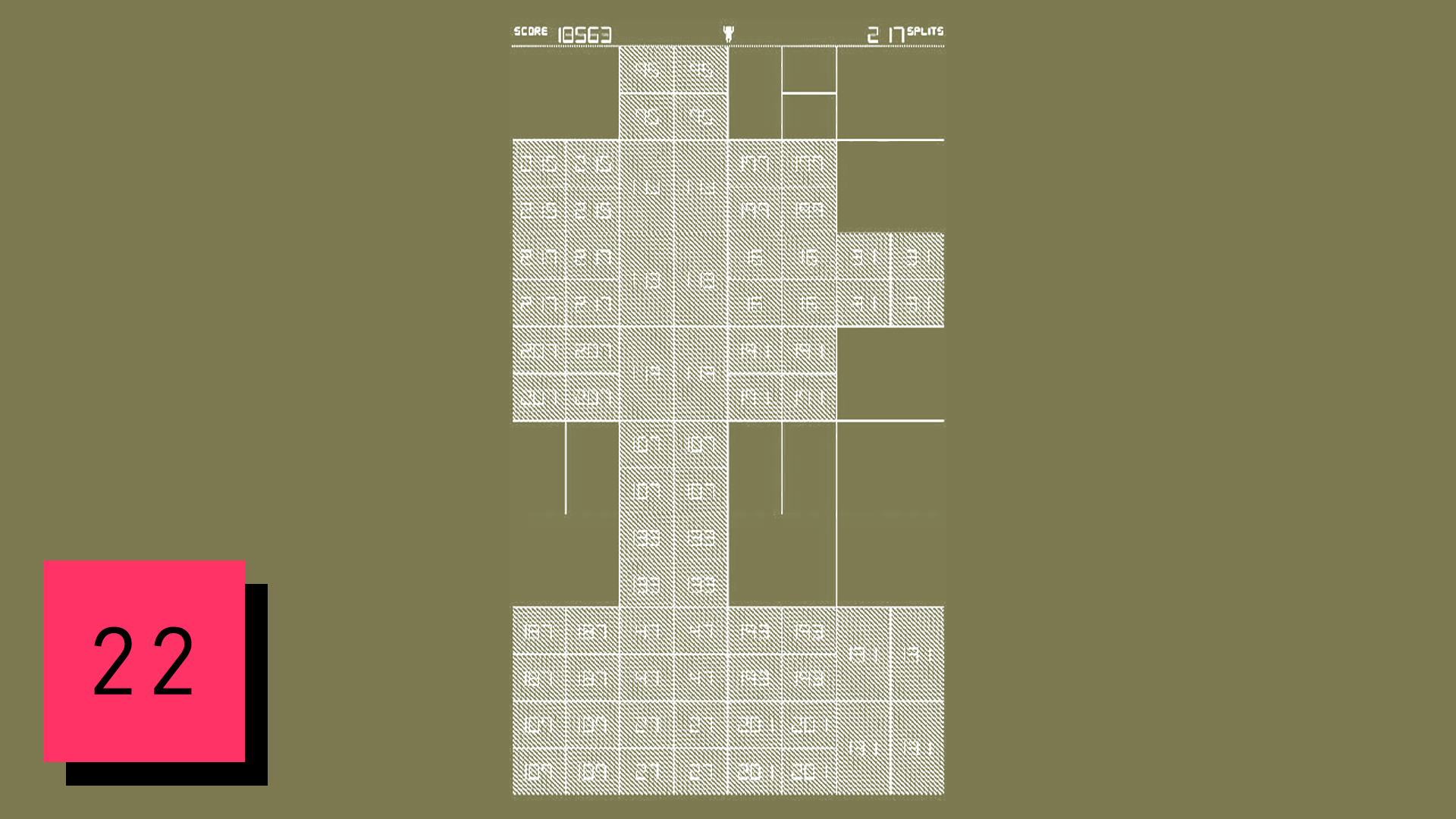

22. SPL-T (Simogo)

In September, SPL-T crash-landed on our planet like an elegant alien drone. It was released as a surprise, with no more PR run-up than a few winky notes on Twitter. To those familiar with Simogo’s impressive repertoire of recent games—story-heavy titles like Year Walk, Device 6, and The Sailor’s Dream—SPL-T was especially baffling for its design: a simple, two-color arcade puzzler, a story told in nothing but numbers on a grid.

That’s all there is to it, right? Tap a few times, make a few splits, and you can just walk away aaaaany time you want. But not so fast. By the time you wrap your head around SPL-T’s rules, its dark mathematical powers have already dug into the folds in your brain. SPL-T possesses a kind of puzzle magic that feels elemental; it’s a game that you could see the ancient Egyptians playing, if only they had smartphones.

Suspicion lingers about whether SPL-T really is as simple as it seems, especially given Simogo’s history for hiding tricks up their sleeves. Some point to the file size of the game, saying that at 70 megabytes, a game so ruthlessly spare must be hiding something. Others point to the inexplicable flashes of text that appear extremely infrequently at random times in the game.

Maybe SPL-T is exactly what it seems—in which case, Simogo has created another beguiling game, solidifying their status as one of the most multifaceted teams working. On the other hand, maybe it won’t be long before we all figure out SPL-T’s secrets, in which case we’ll be talking about it again in 2016. –Chase Ramsey

21. Sylvio (Apostrophe)

If it’s an error, it’s in the realm of the unknown. The supernatural tends to live in the discrepancies of the technological. Spirits only show themselves in the floating orbs of video, angels whisper in the white noise of radio, while the devil murmurs on a Wings record playing backwards. We’re even making fireside tales these days about videogames of an unknown origin or their uncomfortable, almost sentient glitches. We are captivated and terrified of the ghosts in the machine. You take that terror with you in Sylvio, even if its hero shrugs them off.

Juliette Waters is not afraid of ghosts. She seeks them out professionally, driving into abandoned theme parks, hospitals and other clearly inadvisable locales to document the buried, miserable histories and the dead disclosing their own eulogies. While you have a weapon—a glorified tennis-ball shooter—and you can fight, the threat of harm isn’t what’s chilling, but a stuffy, dense atmosphere. That danger is all around you even if it can’t kill you. It’s toying with you.

Bad history and continuing omens. Fear itself. The main focus on the game isn’t busting ghosts but recording them, proving what you just saw was real and manually, faithfully, combing through magnetic tape for glimpses of dialogue. As Juliette casually strolls deeper into hell, the player turns into geeked-out Shaggy, hestitating in the doorway and asking if it this is completely necessary. For Juliette, it is. –Zack Kotzer

20. Alto’s Adventure (Snowman)

In Alto’s Adventure, every run down the mountain starts with a single echoing note, a chime, ringing through the mountains, almost as a statement of definition—“You are here,” it says, and it begins.

As you begin to descend, a two-chord alternating arpeggio and a first set of four llamas—always the same notes, always the same four animals, the same verdant green isosceles pines—give the world its initial movement. As you progress, things will vary a bit. The sun sets and rises, framing the slopes in dusk, darkness, and dawn. A woodwind melody is added to the piano. You pass through forests and towns. You use an incline to launch yourself into the air. You stay there forever, until the ground rises to meet you. You land soft or hard. The single note sounds again.

It is almost unimportant that Alto’s Adventure is a snowboarding game. Its representation of snowboarding is so idealized, so simplified, so perfected as to bear little resemblance to strapping one’s feet to a piece of fiberglass and sliding over the cold, sharp, particular snow of a cold, sharp particular day. The world of Alto’s Adventure is as smooth and flawless as the glass of your touchscreen. It is color and movement as attention and meditation, a statement of presence, and a method of being within a world with just enough room for you to offer up your own imperfection. It is a gift, the one thing that was missing.

This rhythm, slide and fall, is what brings the sharp, perfect world to life. It is the one way to make the chime ring again. –Gavin Craig

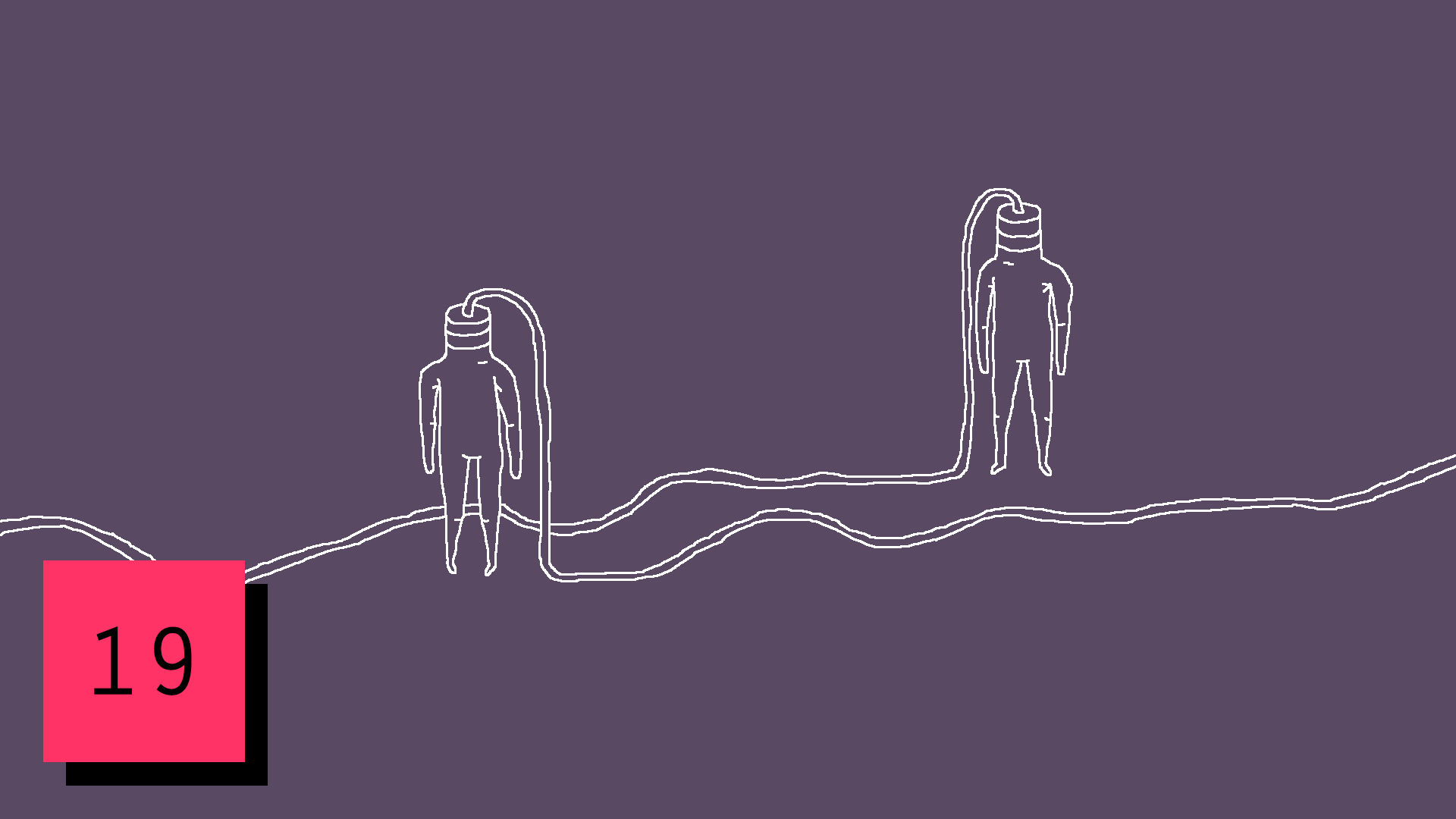

19. Plug & Play (Etter Studio)

A wet finger in a socket. “Don’t put that in there!” a mother cries out. Bad baby. We all learn this. At first it’s our fingers, but as we grow it expands to our nosiness, our ideas, our perversions. Keep your hands to yourself. And everything else, too.

Plug & Play has us toy with these lessons that run through our lives. It stretches out across humanity. From its disturbing allusion to Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam,” with two elongated fingers and a choral harmony, all the way up to you, clumsily wrestling with the cords like a nest of plastic vipers behind your TV. The plug- and socket-headed cast of peculiar anthropoids act as subjects. We tease, bully, and bring them together in love. They act out the confusion of heartbreak and the ease with which violence can escalate between us. Genders are implied, as a plug becomes a socket by passing its symbolic metal prongs in a shocking act of defecation.

It has the range of a Pasolini film, trading vulgar images of sex and sleaze with a philosophically charged visual poetry, all of it cleverly cut and underlined by a faint tragedy: us searching blindly in life for meaning and love. That it does all this in 10 minutes and through a series of simple interactions speaks of its potency. Whether you find it plainly weird or you see deeper into it, Plug & Play lingers, much like its lasting image of a plug-in finger made erect or flaccid at the push of a button. –Chris Priestman

18. Metamorphabet (Vector Park)

When I was a child, one of the most popular books at the Phil-Mont Christian Academy elementary school was Animalia by the Australian cartoonist Graeme Base. Animalia was a book of letters but also a book of discovery, in which each page comprised a letter of the alphabet consumed by an elaborate setpiece of animals starting with the same letter. There was peacock’s plumage and hairy hogs hurrying home and crusty crayfish and you get the idea. What’s important is that 1.) I was old enough to read on my own, thus removing the need to learn my letters, and 2.) there was a puzzle wrapped throughout. Base hid his own face and many other objects through these monographs, encouraging one to discover the story within the story of these letters.

The idea at the heart of Animalia–that letters in and of themselves can be metaphors for ideas and objects–was profound to me as a child, and came alive again to me in Patrick Smith’s Metamorphabet. A deceptively facile toy-like thing, Metamorphabet is both the learning tool of choice for the touch generation and also an ode to the subtlety of the form and contours of the Latin alphabet. Bugs bloom from a bird’s beak atop a bearded B. Neighbors peak out from a towering N. An elephant E precariously balances atop a rolling Earth. Each scene is preganant with a healthy mystery, and each letter is presented with a sans serif simplicity, awaiting only your prodding to begin its metamorphosis. As a writer, it’s a reminder of the possibility of not just words, but the lowly letter, the building blocks upon which each written thought blooms. We forget this old simple truth when we send texts or emails in a way but Metamorphabet breathes new life into these shapes again. –Jamin Warren

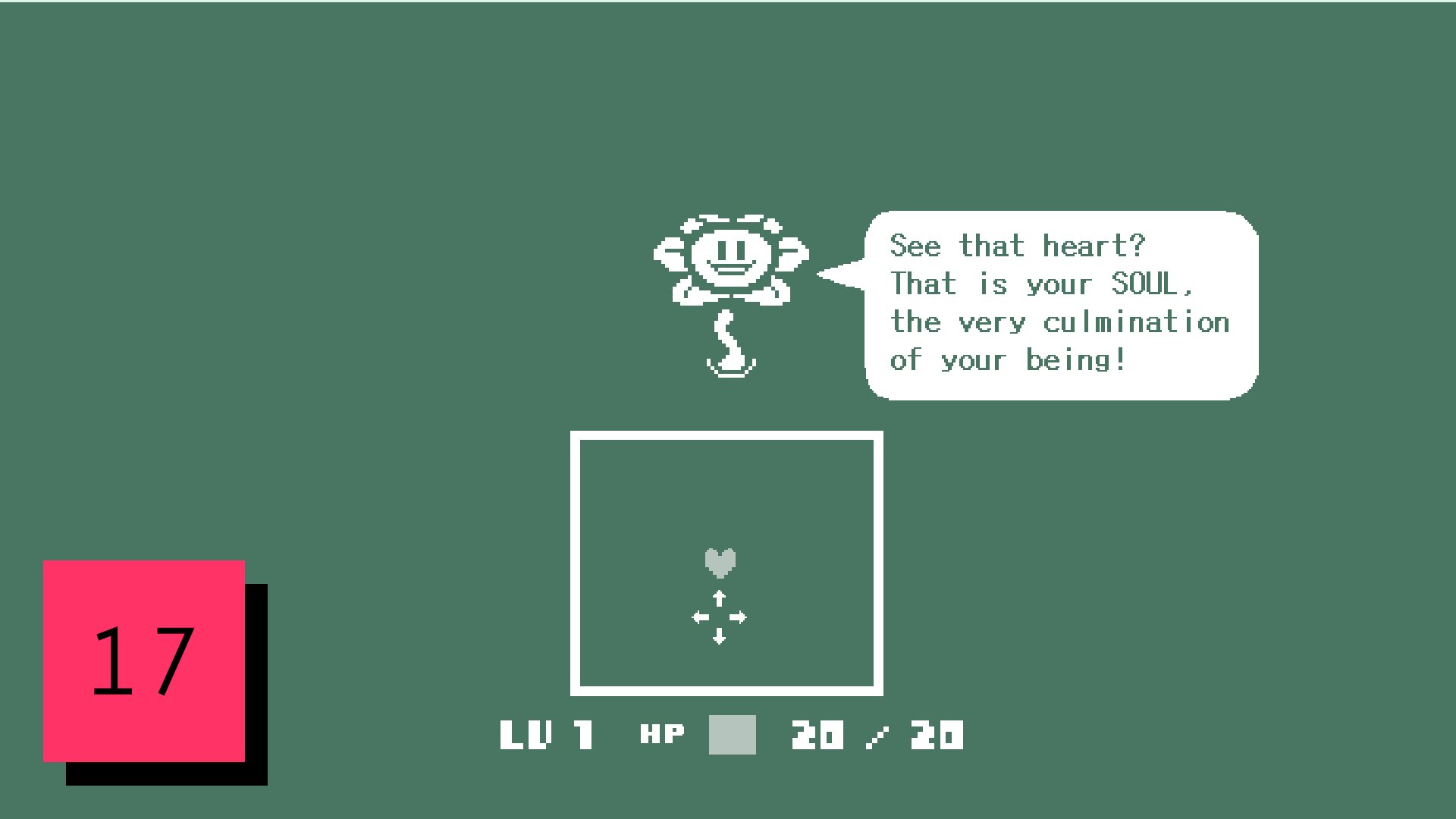

17. Undertale (Toby Fox)

Many games would rather keep how you do things separate from why you’re doing them. Shoot a bunch of dudes and earn a cutscene. Battle through a dungeon before chatting up the residents of the next town. Like ships passing in the night, mechanics and plot float along beautifully detached from, and indifferent to, the other. Undertale, however, collapses the space between them. Setting you loose in a claustrophobic world of moody chiptunes and quirky misfits, the game asks you to move beyond genre cliches and conventional grinds and engage with it on a deeper level. Everything you meet is a potential friend or villain. Instead of being scripted, the game’s truth is inextricably linked to the player’s own.

Calling into question the very idea of enemy encounters, Undertale mixes conversations with combat, tearing down the traditional barriers between towns and dungeons, making every space a unique new opportunity to be negotiated. Designer Toby Fox’s flat, high-contrast aesthetic serves only as a retro disguise for a much more advanced and ambiguous geometry of human emotion and morality. That Undertale handles such interpersonal complexity not only with narrative charm and precision, but also a sleek interactive design that makes combat and dialogue as twitchy as a Contra level, only clarifies the breadth of its achievement. –Ethan Gach

16. Sunless Sea (Failbetter Games)

Even in a year rich in Victoriana, Sunless Sea rises up as uniquely in communion with that era of empire. First is that reference to Coleridge’s Kubla Khan contained in the game’s title, a connection to opium dreams, romantic lyric and a world oriented from a logical West to a mythical East. Into those symbols of romanticism Failbetter Games feeds the decay and doubt of early modernism, generating a powerful literary voice. Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Lovecraft’s The Call of Cthulhu hang like great spectres over both the steamship voyages and the subterranean setting of the game, but there are deeper connections to be plumbed, the “Hollow Men” of Eliot’s Wasteland, the “Kimmerian lands” of Pound’s Cantos. The game is as unforgiving as these epics, rewarding eager explorers with little more than impregnable stories and mysterious artefacts. The mutiny of crews on dark seas, a shipwreck webbed in spider silk, the stygian depths of a postman cult. Those who dare to wander come back with irresolvable tales, filled with half-understood words and names all but lost to the wind. There is wit, too, in colonies of regal guinea pigs, or the utility of a wretched mog, and a playful teasing that tempts you into terrible decisions of unclear provenance. But all ends are played out in a minor-tone, and all Sunless Sea can truly promise is a drunken stumble down a salt-warped path of sodden stories before the inevitable dark. –Gareth Damian Martin

15. Life is Strange (Dontnod)

When the first episode of Dontnod’s Life Is Strange dropped, way back in January, there was no way to predict the juggernaut it would become. The lumpy, post-Telltale adventure game became a syncretic whirlwind, refracting teenage girlhood through everything from Twin Peaks to Hideo Kojima. It is the grand symphony to Gone Home’s hushed ballad, both of them mining a similar vein of longing and nostalgia.

Naturally, it didn’t all work. Notably, the script never quite grasps teen patois, although it improves with successive episodes to a point where the finale’s pivotal reprise of the game’s first moments throws the difference into cringeworthy relief. But it understands the outsize pain, confusion, and uncertainty of teenage life on an elemental level. You might say that under its clumsy bluster there’s real heart; it’s a young-adult videogame both in form and content.

The story of Life Is Strange manages to make its central mechanic of time-travel into something metaphorically rich: what wouldn’t a teenager give to be able to game his or her way into every clique at school? To always say the right thing? To be able to help anyone out of any situation? This is the game’s true triumph: at every turn it neatly folds meaning into action, until the unfairness of the climax becomes indistinguishable from the unfairness of life itself.

Dontnod navigate the story’s most affecting moments with admirable grace. A suicide attempt; the discovery of a hidden grave; a montage of apocalyptic portent set to Mogwai: they’re all given space to breathe and resonate. Nailing those beats means that the sillier contortions of the time-travel plot have something to anchor them. Time travel may work for the game mechanically, and metaphorically, but as a sci-fi layer to the plot it never feels like anything but a gimmick. None of it is as compelling as the game’s quieter moments.

To that end, the game also boasts a simpler accomplishment: it is the story of two female friends, presented honestly and without prurience. Their dynamic is thoroughly and sensitively explored, in a way unprecedented by games at this level. Yes, Life Is Strange overreaches at times. But when the particulars are this well-drawn, a few clumsy moments are easy to forgive. –Zach Budgor

14. Soma (Frictional Games)

Rare is the artwork that does not assume life is worth living, but instead challenges you to make that discovery for yourself. While SOMA has been praised by many this year as a thoughtful treatise on transhumanism, I think this is too narrow a pigeonhole; it is a masterwork, simply, in humanism.

At its onset, the game presents itself as something you’ve played a thousand times before: sci-fi horror beset with evil robots, ethically questionable scientists, and a dose of protagonist amnesia. Okay, you think, time to once again discover that some things are best left undiscovered, to learn that the real enemy is our own hubris, and to nod in smug satisfaction as whatever villain is at the core of this story finally realizes that any effort to cheat death will inevitably corrupt and crumble.

None of these tropes come to pass. The robots aren’t evil and the scientists were trying to make the best of a catastrophic situation. This isn’t a game about the folly of seeking immortality, but about the depths to which you are willing to go (literally: the game is set deep in the ocean) in order to preserve life. In the act of playing something that feels familiar, you come to realize you are experiencing something daring and new.

Frictional Games borrowed elements from their earlier work, namely Amnesia: The Dark Descent, without succumbing to the temptation to emulate them too closely. SOMA is more exploration than running-and-hiding for your life, more pathos than terror. It is fine-crafted horror of the existential variety, wrapped in a mesmerizing glitch-art aesthetic. Recommended for anyone still grappling with what it means to be human. –Alexander Kriss

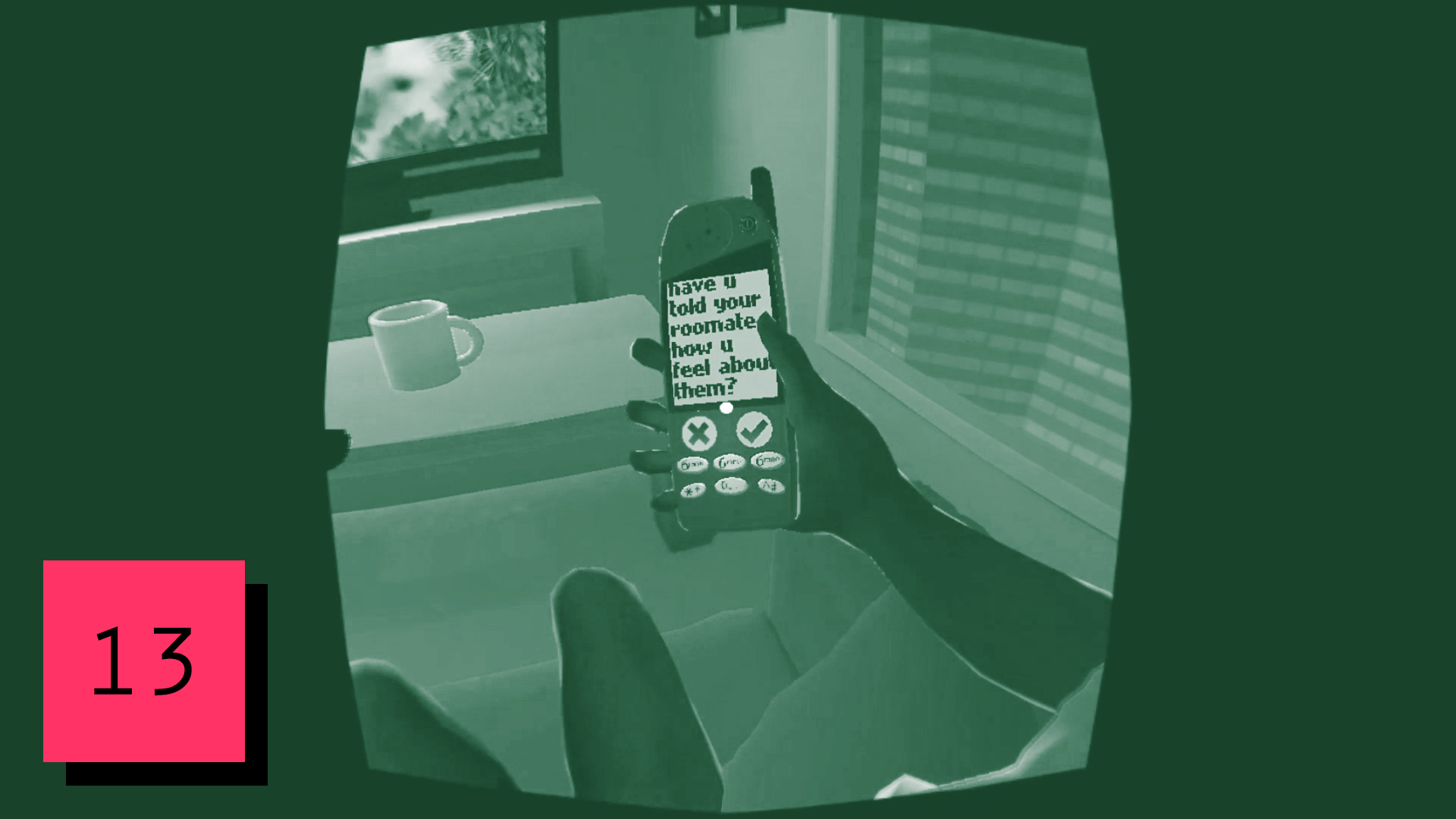

13. Sonic Dreams Collection (Arcane Kids)

“Stare deep in his eyes” reads a text message from Dr Eggman, encouraging you to make the final move in seducing your roommate, Sonic the Hedgehog. So you lean in, angle the cursor until it’s lined up with Sonic’s glitchy, flickering pupils and watch as his face collapses in on itself, forming a swirling portal which sucks you and your phone into another world. This is Sonic Dreams Collection, and when you stare into the eyes of the eponymous hedgehog, you are looking down the barrel of a gun, into the darkest reaches of internet porn subculture.

Every bizarre image returned in a Google search of “Sonic rule 34” slithers its way into Dreams Collection. Every horrifying contortion created by tilting the cartridge on a Sega Genesis finds a home here. Presented as a series of hidden mini-games, discovered while exploring the code of an old Sonic Dreamcast disc, the Dreams Collection is an hilarious nightmare, where innocent videogame characters come to be tortured, force-fed, tickled, filmed having sex, ingested and then re-birthed.

Sonic Dreams Collection oozes sleaze—it’s a compilation of fecund and perverted fantasies, some sexual, some violent, some both. At the same time, creator Arcane Kids has a genuine propensity for the surreal. An homage perhaps to the worlds of DeviantArt and /b/, Sonic Dreams Collection never feels affected, or deliberately made to shock. Whether laughing, wincing or sitting there in total bafflement, with each new vignette you fall deeper into its eyes. –Ed Smith

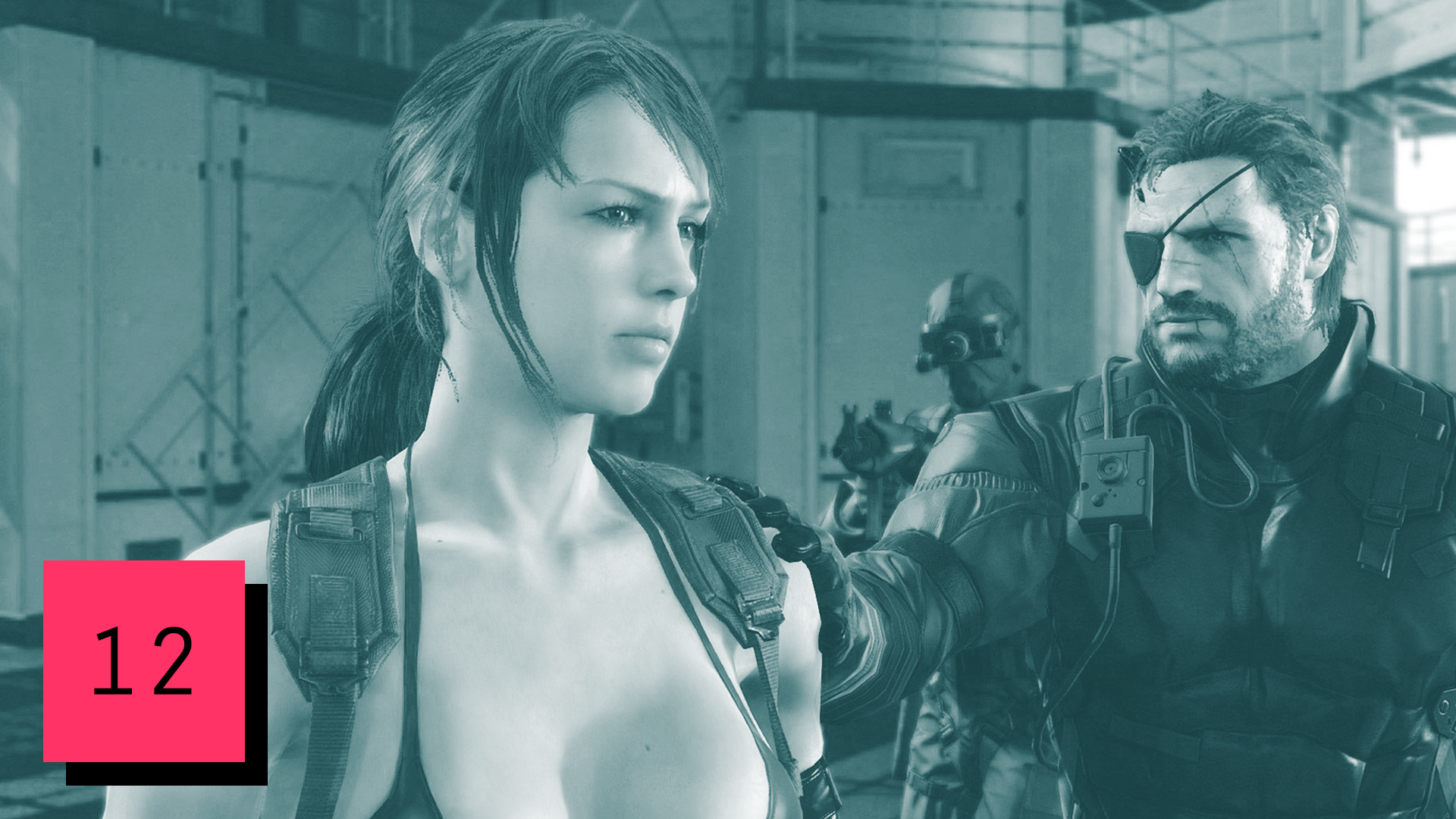

12. Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain (Konami)

“When you’re wounded and left on Afghanistan’s plains,

And the women come out to cut up what remains,

Jest roll on your rifle and blow out brains

An’ go to your Gawd like a soldier”

–Rudyard Kipling, “The Young British Soldier” (1892)

This verse, written in a vulgar English accent, echoed in my head as I played Metal Gear Solid: The Phantom Pain. Despite the companions that can accompany Snake, The Phantom Pain remains a consistently lonely game, one that has much in common with the late fiction of the Victorian, era as the seams of great Empires began to tear.

Afghanistan was a key theater of war in “The Great Game,” the coldly playful title given to Britain and Russia’s strategic battle for control of Central Asia at the expense of the people who lived there. The Great Game was one of intelligence and subterfuge as much as open conflict, and the writers like Rudyard Kipling (whose novel Kim popularized the term “The Great Game”) decided to exercise their disillusionment in their fiction and poetry. These are the ideals that Snake, in his isolation, fights to dissolve; he seeks a military without borders, free from ideologies that built a legacy of colonialism in the name of that hollow promise of “progress.” As I explored the desert, a place absent of local people due to constant bombings, I thought back on the legacy of those stories of military glory abroad, and how they changed when writers like Kipling and Conrad looked at the people affected by the colonial project instead of those foreigners fighting for a region they claimed from a continent away. I like to think that Snake does so, too, in those quiet moments before raiding a base to rescue some prisoner in a Russian camp, or to search for intelligence in a dusty outpost. Or maybe he realizes what the people who lived there realized over half a century before him—that, as Prince Faisal explains in Lawrence of Arabia, “There is nothing in the desert. And no man needs nothing.” Then, he silently slips a round in the chamber and plans his next move. –David Chandler

11. Cibele (Nina Freeman)

Cibele is about more than coming of age, bubblegum adolescence and budding online romance; it’s about how the internet transforms them. Designer and star (and former Kill Screen intern) Nina Freeman’s greatest achievement in Cibele is in how carefully she preserves the layers of unawareness and self-deception in her younger self. There is no revelation in Cibele, just breaking emotion. Rather than trim her old poetry or fabricate old fanart, Nina dumps everything unedited and raw for players to root through on her desktop. As with Her Story, the focus here is all about the player’s experience and understanding of its protagonist’s cluttered id.

Who is Nina? Cibele carefully holds in tension the multitudinous and contradicting facets Nina presents to each different strata of her world: to the forums, to her Xanga, to her MMO guild, to her crush, to herself. It is a kind of anti-confessional: 19-year-old Nina doesn’t even know herself well enough to articulate her crises. Apart from a few tender FMV sequences, Cibele leaves the editorializing up to the player. The game, like young Nina herself, feels fresh, timorous, and painstakingly honest. –Josiah “Duke” Harrist

10. Until Dawn (Supermassive Games)

In a year filled with predictably horrible (Rise of the Tomb Raider) and unpredictably horrible (The Order: 1886) “cinematic” games, Until Dawn emerged from the muck like a blood-soaked angel of death. From its long and turbulent development period to its association with the dreaded “interactive movie” genre, Until Dawn had every reason to fail. Instead, it QTEed its way into our hearts by presenting a new way forward for big-budget narrative games, while also simultaneously contributing to game genres that have come to equivocate “survival” with “shotgun,” and “choice” with “button press.” At the heart of Until Dawn’s success is not only a deep respect for horror movies, but also an equal respect for interactivity, and an inspired vision for how a marriage between the two can amplify rather than detract from both.

Put simply: Until Dawn is the best of both worlds. It doesn’t lean on tropes, but incorporates them boldly; the rules of B-movie horror flicks are used to give you just enough of an idea of what’s going on or what might happen next—information you can then use to make informed decisions and keep characters alive. Going against the trend of overtly obvious “if this decision, then that branching path” storytelling, the decision-making mechanic in Until Dawn works more like a sandbox, with your choices interacting and culminating into small and big ripples. This approach also presents a solution to the fundamental problem with branching narrative games: how do you split authorship—between allowing a player to effect the plot while also telling a coherent story? Well, instead of creating an antagonistic relationship between the game and player input, Until Dawn asks you to try and peek behind the curtain. While simultaneously executing horror tropes better than most movies, it also gives the most contrived gaming conventions a new purpose. From collectibles to character stats and even motion controls, every design choice feels essential.

Above all else, Until Dawn hints at how games can contribute to our human relationship to fear. Every medium has left its mark on how we understand this primordial instinct. Oral storytelling rendered horror a communal activity which both entertained and frightened listeners into following social conventions. Horror movies and TV shows have become a way for societies to cope with the fears of a certain age, era, or national identity, from Polanski capturing the paranoid disillusionment of the 1970s in The Tenant to The Walking Dead’s suggestion that technology is rendering its audience a shambling, shuffling, brain-dead mass.

In contrast, Until Dawn makes an argument for the personal relationship to horror, moving away from the collective. Videogames allow you to explore the specifics of your individual fears. Counterintuitively, Until Dawn’s attempts to tailor jump-scares to the player’s individual phobias was its least-satisfying mechanic. But by allowing you to become Carol Clover’s “final girl” in an interactive setting, the game makes you face how you cope with fear and by extension who you are as a person. Removing the distance of film and the communal aspect of campfire ghost stories, Until Dawn leaves you alone in a dark room with whatever goes bump in the night. Whether or not you can live with who you are when the sun rises and the lights come back on is entirely up to you. –Jess Joho

9. The Beginner’s Guide (Everything Unlimited Ltd.)

To be famous is to be popular yet misunderstood; successful but never satisfied; praised but also hated. Dave Chappelle once indicted fame as a “sick” institution, a pressure chamber of horrendous force capable of cracking even the toughest, most gracious, most righteous of those among us.

In 2013, Davey Wreden made an immensely successful game called The Stanley Parable and was nearly crushed by the internet fame that followed. He recalls the aftermath of Stanley’s release as a period of trauma: “Thousands of people asking you to carry some amount of weight for them, to hear them, to talk to them, to tell them that things are going to be okay, to not turn them away.” Wreden’s problem wasn’t that his audience was full of bad people, per se; it was the sudden weight of his art that overwhelmed him, as if this notebook he’d been carrying around for years had suddenly been crammed with the notes of hundreds of thousands of strangers. Among this clutter, where were his own ideas? Where was his inspiration? Did these things ever exist to begin with? And so Wreden walled himself off from the world, living a mostly secluded lifestyle until two years later, when he finally emerged with a new game called The Beginner’s Guide.

Here was a game that shared the same DNA as The Stanley Parable: both fully narrated, both teeming with ideas about the videogame medium, both sharing the same Source engine aesthetic. And yet The Beginner’s Guide felt worlds closer to us than The Stanley Parable did. This was Wreden himself behind the mic, not the golden-voiced Kevan Brighting. This was intimate, a direct appeal to an estranged friend. This was personal, beginning with Wreden giving out his own personal email address. This was painful, twisting and turning down paths so dark we could hardly bear to look down them.

For most people who walked briskly through its hour-and-a-half runtime, The Beginner’s Guide was a high-concept work filled with ideas to sift through and potential motives to be uncovered. We delved into it like a piece of literature, re-playing its scenes and wondering whether Coda was real; what that prison might represent; whether the ending was meant to be a send-up of the audience or the creator. It felt like an artistic statement, a fleshed-out manifesto, the beginning of a dialogue. But The Beginner’s Guide’s greatest accomplishment is that it wasn’t actually any of these things.

As people who play videogames, we’ve all been spoiled. We expect every experience to be focus-grouped to our perfect liking, to treat us like royalty and to reward us like gods. The Beginner’s Guide is not for us; it is a rambling collection of thoughts and questions assembled by and for its creator.

In the game’s final sequence, Wreden reaches a desperation point, his voice crackling and fumbling like it’s about to collapse under its own weight. Meanwhile, we sit alone on the other side of our computer screens, paralyzed, unable to lend a hand. Maybe this is what Davey felt like after The Stanley Parable: forever subjugated by the audience on the other side of the screen, no longer a freely acting agent of his own. The Beginner’s Guide is his attempt to face the problem; a last ditch effort to deconstruct it and confront it, an author reaching out by any means necessary but still failing to make contact. Because sometimes art isn’t enough. Sometimes you need people. –Joshua Calixto

8. Downwell (Moppin)

Videogames’ go-to aesthetic mode is maximalism. Gameworlds often get suffused with enough stuff to fill out the disc, a real achievement in the age of Blu-ray: cutscenes, non-player characters, tertiary and quaternary quests, easter eggs, new game+, etc. Minimalism, maximalism’s antipode, means less stuff, but under the guiding principle that a meticulously built Less is More than a simple heaping-on.

Samuel Beckett, the minimalist modernist writer and assistant to the crown prince of literary maximalism, James Joyce, supposedly said that, “Joyce put everything into the novel; I took everything out.” Apocryphal or not, Beckett’s one-liner shows that there’s not actually a straight line between minimalism and maximalism, with each term at opposite ends of a spectrum. Rather, that line seems to bend into a circle: Minimalism (Waiting for Godot) is more closely related to maximalism (Ulysses) than a safe middle is to either pole.

Enter Downwell. While more allied with minimalism than the maximalism of a game like Witcher 3, Downwell delivers both literal and metaphoric depth (you are falling down a well, after all) of a kind with its maximalist peers.

Restraint seems to be Downwell’s governing ethos. You have these gun boots (kinda like Bayonetta’s, minus the 8” heel) that allow for the game’s stomach-dropping experience of falling-while-shooting and shooting to control that fall. And yet, it’s to your advantage to use the gun boots as little as possible, since shooting injects a hell of a lot of entropy into the system. Downwell creates the temptation to shoot for the mechanical pleasure of the thing and for the generic (in the sense of genre) reason that you shoot in shooting games. Yet this one systematically rewards you for not shooting, since covering yourself also means destroying ground on which you could land and reload.

As a genre, the roguelike thrills through a cruel risk-reward structure where you go all-in on every hand. Spelunky, Downwell’s stated inspiration, is a master class in the art of loss. So, the way in which you fail actually becomes far more important than the way you succeed, since failure overawes success so completely. You are always spectacularly at fault for your failures in Downwell, and a single mistake often leads to a disproportionate punishment. Everything’s going fine when suddenly you shoot out a platform you’d been hoping to land on, miss an enemy, keep falling, pick up speed, well racing past you, enemies flying up and careening down, trying to kill you all the way back to the top. What had been your slow-but-steady progress down is utterly forgotten in the pandemonium: all hell has broken loose, and you have to get to the exit before your (numerous) mistakes catch up with you. As you attempt to impose order on a system that resists it, you start to uncover the beauty of Downwell’s design. And each time you fail, you brush off another layer, coming back to see what lies beneath. –Erik Fredner

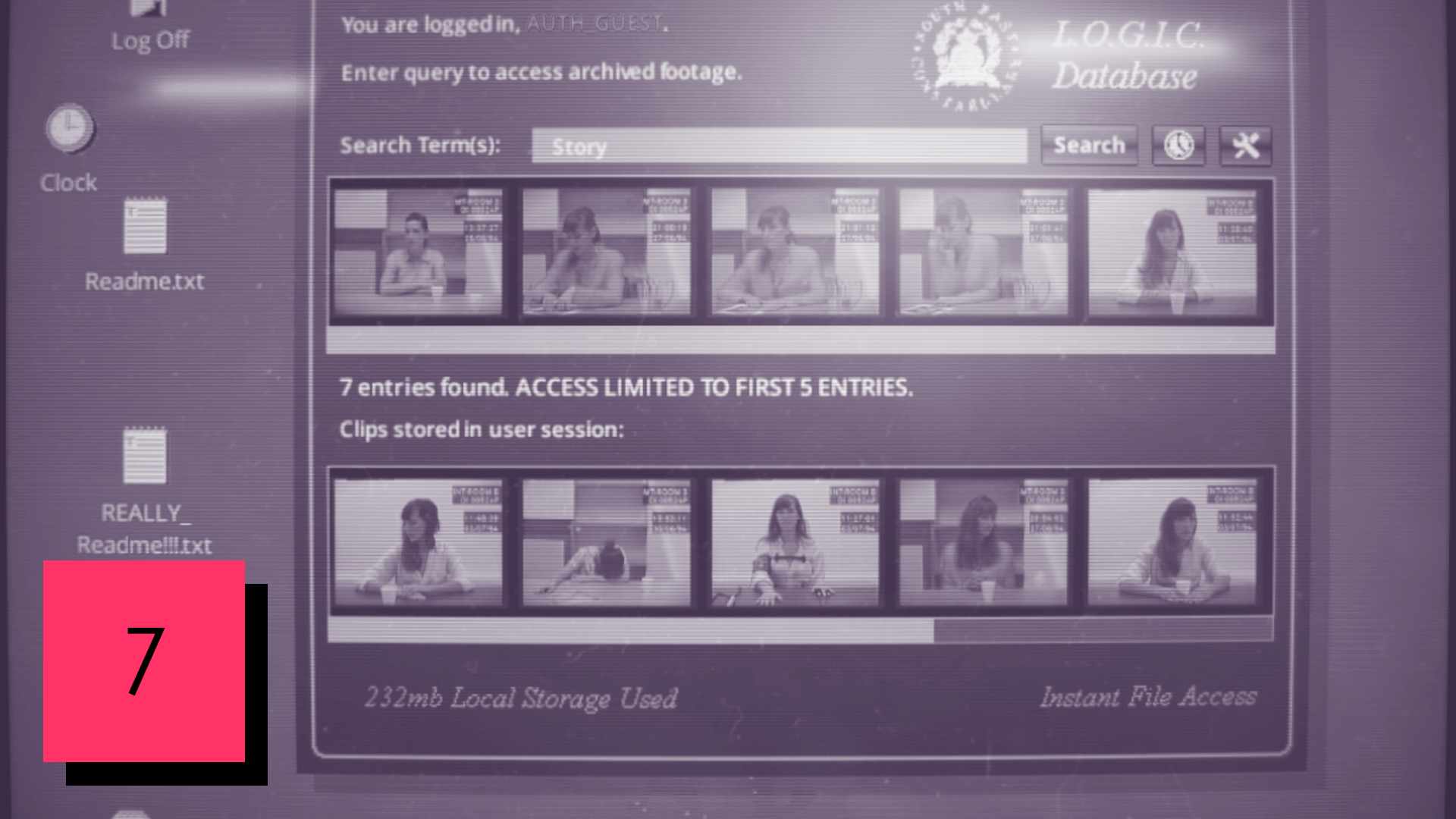

7. Her Story (Sam Barlow)

What has happened to us. It’s one thing to live online but it’s another thing to believe the entire universe, and all of history, has been transposed on to it. Every social media service, every user, often breaks down into groupthink detective agencies, in which both celebrity drama and global conspiracies can be deducted merely by linking tweets and posts into a conspiracy web. The thinking is that every needed blip of information has ended up somewhere globally accessible.

Her Story is a whodunnit inspired by this peculiar behavior. In particular, it reflects the reactions to the Jodi Arias interrogation videos that found their way online, and the digital jury that felt they could shut the strange case of the 2008 Arizona killing.

Her Story provides everything you’ll need to know about a 1994 murder in the form of a series of recorded interrogations, but it won’t gift everything to you. You’ll need to navigate through a series of archival footage, most less than a minute long, on a stodgy user interface. Video inelegantly listed not by chronological order but by keywords, forcing you to follow your gut, even when (especially when) it’s wrong. It is sleuthing via an advent calendar, poking your finger through a tiny door hoping to fish out the best candy.

It is a cut-up mystery. Each segment can be illuminary, frustrating or distracting, depending on where you’ve arrived there from and what you’re looking for. You can stumble on to the final reveal without even realizing it, the useless conflating with the climactic depending on context. You’re being battered and toyed with by your own notions, and being headstrong about a certain presumption can only lead you further into a dead end. It’s a rare of example of when insecurity can be a helpful tool in a videogame. As the feeds of information and ideas skew between grit and gothic, the grounded and the supremely weird, you’re asked, required, to show caution and hesitation. This turns it into an exercise in the sort of discrepancy we’ve abandoned in the world the game is based on. –Zack Kotzer

6. Rocket League (Psyonix)

Holy fucking shit: this game! What delirious, geometric joy! And also what idiocy! Rocket League may be the platonic ideal of a videogame: here we have cars playing soccer. They appear to be in some sort of car world, in which there are only cars; to wit, there is a statue of a car kicking a soccer ball, rather than a person kicking it, and there is no one driving that car. In the intergalactic Olympic arenas in which these car-gladiators do battle, they are cheered on by pitiless mobs—of cars, roaring in the stands. And what fuels them?

The same thing that fuels us all: victory. The feeling when you gun it from mid-field to a corner, dodging between opposing defenders, to front-flip a ball just as it bounces off the wall and send that sucker screaming into the goal. Or when you hop over a ball as it gradually breaks the plane of your goal, twist in a full circle only sorta intentionally, and knock it, with your car’s butt, to a teammate waiting nearby, who then races downfield. Or when you silence that glib shit on the opposing team who spammed “LOL!” when you scored on yourself—which you only did because you were the only person on your team interested in defending, apparently—by hopping over him to knock in the game-winner with 5 seconds left. You spam “LOL!” at him as the clock ticks out. You know, in that moment, greatness.

In some ways, the game is a success of obviousness. The still-uncracked-nut of competitive gaming is spectatorship—even something streamlined like Hearthstone requires foreknowledge and meta analysis—but Rocket League’s genius is all there, right on the screen. I thought of posting, for this blurb, a series of .gifs: a net-to-net feat of juggling, aerial hit after aerial hit, a life-givingly daring save, the bizarro inversions of mutations and hockey, pretty much anything Kronovi does. To watch Rocket League is to understand it. But play the game long enough—and who that has started to play it hasn’t spent an evening or weekend or summer in its thrall?—and it starts to feel increasingly sublime, even revolutionary. The floaty physics and terse, physical engagements start to feel almost like an old console shooter, innate but new. And then eventually even the whole car thing makes sense: if the first-person shooter abstracted the player to an eye with a gun, why wouldn’t a soccer game eventually turn the player into just a foot, jetting and flipping and spinning down the field, riding up walls and blasting into the sky?

The car is always a metaphor, after all. As in George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road, the point is not the automobiles but the space between them, and the mighty, human engines that power them. Rocket League lets us ride eternal into Valhalla, shiny and chrome, and also wearing a pirate hat or whatever. –Clayton Purdom

5. Neko Atsume (Hit-Point)

Neko Atsume is the virtual pet game I never knew I needed in my life. The Japanese stray-cat feeding game for mobile devices was a surprise international hit, and a hit, in part, because of its surprise. Up until just a couple months ago, Neko Atsume only contained Japanese text, with no option for English translations. The illustrative iconography of buttons and items, combined with most Westerners’ inability to read Japanese, struck an odd, eminently playable balance between user-friendliness and inscrutability (note to English-speakers: stick to the Japanese text and avoid the Guy Fieri puns you’re better off not knowing about). The initial weeks of Neko Atsume’s outside-of-Japan discovery were a magical time of screenshot sharing; a land grab set in to see who could show off the most ridiculous kitty that happened to wander into their virtual abode. It didn’t hurt that the cat illustrations were also supremely adorable. Have you seen the one that jumps and grabs the butterfly toy on a string? (!!!)

Whenever I’ve attempted to corral my cat in real life, the experience has been anything but pleasant or efficient, but in Neko Atsume’s game world, enticing cats out of hiding with alluring toys and sushi is downright delightful. While many free-to-play phone games set out to confuse players with multiple currencies and delayed time-tables in order to get the rewards they’ve been strung along to receive, Neko Atsume keeps it simple: put the cardboard box in the yard and check back later to find a kitty poking its head out the top. Cute! Done. All the while, the most soothing Japanese convenience store muzak (with a tinge of Banjo Kazooie) loops endlessly in the background. To be fair, there are both gray and gold sardines to use as money, and cats don’t show up instantaneously, but the lack of any fail state removes the pressure to “play well” and thus disincentivizes the need to spend real money on the game. Furthermore, you don’t really own the cats that come to play on your porch, either.

They’re just visitors, and one assumes that if you forget to put out a fresh plate of chow, they must be playing and eating somewhere else (the screenshots are on the internet to prove it). The game’s title loosely translates in English as “cat gathering,” which you could take in one of two ways: either as a charge to gather as many cats as possible, or to take on the role of feline party planner and attempt to stage evermore elaborate cat gatherings. In truth, it’s probably a bit of both. If merely getting a cat with its own backpack and a pickaxe to wander onto your virtual back patio isn’t reward enough, you can fill out a collector’s picture book by taking screenshots of each cat as they appear. On the other hand, you can curate cat gatherings along particular themes like the Wild West or a posh cocktail party. All of which is very goofy, but also entirely the point. With a Nintendo-like sheen, Neko Atsume is a game thoughtfully engineered to inspire delight. –Dan Solberg

4. Bloodborne (From Software)

“You’re in the know, right?”

Of all the things you find squirming and shaking down the streets of Yharnam, none are more curious than that message. It’s a sentence that hunters can leave in the skinless hands of the game’s messengers, who unroll the text to show players in other worlds. Placed in front of a window, the words prompt you to break the glass; over by a ledge, they cue you to look for the rifleman waiting below. For new players, the hint just means look again. But it serves another purpose for returning hunters, the second- and third-timers who already know what it means to visit Iosefka’s door or watch the grasping blue light outside Cathedral Ward. For those inducted into the game’s mysteries, the message is a sort of secret handshake. And anyone preoccupied with the game’s peculiar definition of insight may find the choice of words sinister: in Yharnam, to be “in the know” is to be insane.

Making players speak and think in the game’s own voice is one of the Souls series’ oldest tricks. The famous warning of the first game was self-mythologizing: “The true Demon’s Souls starts here.” In the more muscular Dark Souls, “Praise the sun!” became a catchphrase soon after release. In Bloodborne, a game fixated on knowledge and madness, the language is allusive and faintly derisive. It won’t just come out and say “you know what to do”; the question tag, “right,” is there to doubt that the player really understands. Sometimes when you find the question glowing on the cobblestones of an empty alley, or printed on the rheumy turf of a nightmare, the useless clue reads as a taunt.

This is all to say that the dread you feel when first exploring Bloodborne never really evaporates, even after you’ve joined the society of players who are truly, exhaustively in the know. You can process all the grand revelations—the “eldritch truth” found after killing Rom, the final descent of the Moon Presence—and feel like the whole cosmology is almost within your reach. You can learn to whip feet at the periphery of the threaded cane’s range until their owners topple over, or sweep the Holy Moonlight Sword over beasts close enough to eat both the blade and the cosmic wave riding on it. (“Cosmic” effects in Bloodborne can be at times as ubiquitous as Kirby Krackle, though the look is completely different.) You can fine-tune your “rally potential” and blood tap until you puke bullets. But you can never relax. Even when you have the world mapped in your head, it doesn’t settle; it feels like a curtain that might draw back to reveal a greater secret.

The Souls games are famous for their oppressive difficulty, which is the legend that Demon’s Souls wanted players to write on its own floors. But after you learned their tricks, they lightened up; the second run was a victory lap. In Bloodborne it’s the atmosphere, not the layout, that oppresses you. Play it again and it’s still heavy. It’s still keyed up. It’s still, by design, unknowable. –Chris Breault

3. Panoramical (Finji)

In 1896, Wassily Kandinsky was a young artist attending a performance of Wagner’s Lohengrin when he suddenly saw “wild, almost crazy lines” levitating before his eyes. As you can imagine, hallucinating in an opera house, with the full surge of the orchestra swirling around in chirping yellows and brassy reds, made quite an impression on him. He claimed to be able to visualize sound as color and translated them in his paintings. From that mental abnormality came some of the world’s earliest abstract art.

Over a century later, a similar obsession can be found at the heart of Fernando Ramallo and David Kanaga’s Panoramical, which splits the difference between a conventional game, a music visualizer, and a music-creation tool. “What does music look like?” is not a normal question, and the game doesn’t give normal answers. To be sure, gazing directly into the indefinite boundaries of these sounds as they have multiple orgasms across the screen is often a mystifying experience.

But for all of the weird shit going on, Panoramical does us a solid by affixing its electronica to organic shapes and inviting natural environments. Rock formations and mountaintops emit a soothing throb as they slide into the abyss. Glowing seabeds tremolo and strobe with a mischievous synth. Woodwind notes practically lap you in the face. There may be diabolical mathematics at play under the hood (Benoit Mandelbrot, the father of psychedelic geometry, is cited as an influence), but the surface is a hospitable place.

Right from the opening, Panoramical invites you to dive into these post-techno funhouse mirrors. Fortunately for those of us who lack “music game” skills or real-world musical ability, it is nigh-impossible to screw up the playful vibe found within. No matter how recklessly you flail at the knobs, Panoramical somehow always answers back with a composition that is at least musically arousing. The tracks bend and stretch and telescope inside themselves, but will never bite back. Ramallo and Kanaga have concocted a formula that gives you all the benefits of player agency with none of the drawbacks.

That it never sounds “off” is borderline miraculous, when you think about it. The system allows for an insane amount of musical possibilities (somewhere between 128 to the 18th power and 2 to the 8,000,000,000th power, according to this). With a few small twists of the knobs, the entire structure of a song can be flipped inside out, the world deconstructing into something else. Often you will find an amazing, head-nodding jam, then lose it forever, only to stumble across one that sounds nothing like it, but is equally satisfying.

It’s tempting to compare Panoramical with the year’s best electronic albums. After all, artists like ARCA and Oneohtrix Point Never have been creating fluid, flexible beats that step away from rigid binaries, and Panoramical offers that in spades. But the truth is it’s a different beast. The developers have compared it to observing “a manydimensional being’s intersection into our 3-dimensional world.” As weird and utopian as that sounds, the analogy fits. This vision is too big to only listen to it. –Jason Johnson

2. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (The Chinese Room)

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture’s plot unfolds in observations of everyday moments. Two friends say goodbye during an idle moment at a campground; an elderly woman gossips to a disinterested neighbor. These scenes may not seem like much on their surface, but, as a reflection of what’s at stake as the world comes to an end, their mundanity lends a tragic gravity to Rapture’s apocalyptic story far better than any flashy action set-piece.

This is the fundamental strength of the game. Despite the fantastic nature of its sci-fi premise, it’s extraordinarily organic, more concerned with the everyday drama of human relationships than an extensive outlining of its doomsday scenario. Part of this is thanks to the familiarity of its rural English setting and part of it is due to writing that refuses to reduce any of the cast to small-town caricatures. The little radio drama-style vignettes triggered as the player explores are small narrative dioramas providing as much of an understanding of the ordinary hopes and fears of its characters—the torn loyalties at the heart of a faltering marriage or the insecurities of a newly arrived outsider—as they do the hows and whys of the mysterious illness sweeping Rapture’s setting.

The essential humanity of these moments is heightened by Jessica Curry’s tremendous soundtrack. Heavy on warm choral hums and aching violins, the score elevates Rapture’s drama while ensuring, too, that it remains acoustically, physically, and historically grounded. It, like the visuals (which lavish objects as pedestrian as stone benches or the rubber of an overturned bicycle’s tires with incredible detail), is meant to remind the player that the story unfolding before them is about not eternity but the people facing it.

This is Rapture’s great success—it’s a game that achieves grandeur without ever feeling like it needs to leave the everyday lives of its characters behind to do so. It’s a game that understands that the most awe-inspiring events—whether spiritual, scientific, or some combination of the two—can only be understood when portrayed in relative scale with the ordinary world.

None of this would work without the sincerity with which Rapture presents itself and the persistence with which it argues for empathy as a supreme good. The story contains no heroes or villains, only people understanding (with various degrees of difficulty) that they’re bound together—not by politics, religion, or class, but by their humanity. The light that threads the game’s scenes together, literally guiding the player from place to place, is, in many ways, this understanding made material. It suggests that in the face of oblivion, the only thing that can possibly matter is our ability to be kind—to put aside anything other than a willingness to care for one another, unconditionally.

Ultimately, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is a game about love and fear, and the importance of the former in the face of overwhelming terror. And it’s capable of spreading this message without falling into cheap sentimentality or, worse, diluting its tone with the kind of protective cynicism that a less-convinced team might use to shield its honesty. That’s rare, and worth celebrating. –Reid McCarter

1. The Witcher 3 (CD Projekt Red)

It’s hard to describe why The Witcher 3 is good without letting goodness itself—sheer quality—be the unit of measurement. Think of a scene in the game, any scene, and how much care and craftsmanship it exudes from every pixel, every sound, every word, every aesthetic and narrative choice. I still find myself struck by a cutscene from what many regard to be the game’s most captivating and devastating sequence: the Bloody Baron questline, which requires mutant monster-hunter Geralt to travel across the wastes of Velen looking for the wife and daughter of a self-proclaimed provincial despot. At a certain point, Geralt arrives at the cabin of an old woman simply named Gran, hoping to commune with the witches who control her. The camera lingers on a tapestry of three young women; standing before them, she utters a plaintive, withering plea:

Ladies lovely, with power o’er all,

Beseech I thee, answer my call,

Before you a worm crawls, wretched and small…

Gran’s eyes roll back and the witches begin to speak through her, the game’s top-notch facial animation capturing the uncanny microexpressions of the possessed (as opposed to most facial animation, which makes characters look possessed 100% of the time). In the background, a ragged violin pursues its neverending project of furious lamentation. In the foreground, the cinematography—aside from dialogue, consistently the game’s best and most expressive aspect—jumps to and from the figures on the tapestry as they converse with our white-haired hero, heightening their implacability and, as always, heightening his.

One way to praise this scene without just flat-out saying it’s atmospheric as fuck would be to talk about how densely and subtly it blends together elements of other genres and other media. The tapestry looks Pre-Raphaelite, its figures flattened and serpentine; the rhyme could’ve been extracted from the Brothers Grimm; the witches themselves, evil yet never quite inconsistent, take us all the way back to Macbeth. The score draws from a pan-European blend of folk styles; the camerawork proceeds with a canny understanding of the reaction shot, pinging desperately—in a way that heightens the moment’s unease—from Geralt to interlocutors that can’t be framed. Unlike many big-budget games (let’s face it, probably most of them), The Witcher 3 not only behaves as though it’s aware of the existence of other art forms but seems entirely willing to converse with them in both directions. Just as it draws from the techniques of movies, books, and everything else, it confidently offers itself as a possible reference point, as though it weren’t preposterous at all to think that someone’s future movie could be “like The Witcher 3.” I remember one of my favorite professors arguing that the novel was a “literary turducken” because it could contain and consume everything from poetry to classified ads. The Witcher 3 is a multimedia turducken with an entirely un-turducken-like sense of purpose.

At the same time, the game’s way of containing and consuming its own genre—the open-world Western RPG—might be even more impressive. It’s a lot like the best prestige TV (The Sopranos, The Wire, Deadwood, Breaking Bad) in its commitment to transcending the structures of a recognizable genre tradition, meaningfully exploiting what the German critic Hans Robert Jauss called the “horizons of expectation” that we bring with us to any work of art that looks like something we’ve encountered before. The Sopranos depicted a world in which characters had internalized The Godfather to a ridiculous extent, and its most brilliant moments stemmed from an assumption that its audience had done the same.

The Witcher 3, likewise, betrays a canny understanding of what we tend to expect from RPGs like it. There is freedom in The Witcher 3, as there is in any Bethesda game or Dragon Age: Inquisition: freedom to go where you want, do what you want, fight what you want, romance who you want. But it isn’t unlimited freedom, and it often transforms into varieties of constraint: the ostracism that shadows Geralt’s wandering-ronin lifestyle; the sense that most choices are not yours and equally valid but his and equally grim. You can choose Triss or Yennefer, but the choice isn’t completely, synchronically open to you like Miranda vs. Tali vs. Jack; if you’re like me, you’ll get to know Yennefer well after having chosen or not chosen Triss, and feel a measure of resentment toward the unfairnesses of time. Working within a genre that lends itself to systematic sidequesting and obsessive completionism, the game makes a ton of things missable, often silently so. It takes the “open” in “open-world,” the “role-playing” in RPG, and makes both into expressive vehicles of pathos and discomfort. The world is too open, and Geralt’s role in it is wearily, oppressively defined. (Before you a worm crawls, wretched and small…) But perhaps we can derive some comfort from the idea that the open-world as an aesthetic template is more open than ever—to other genres, to other meanings, to a different idea of itself. –Matt Margini