The history of photography could predict the future of videogames

“Wow. That game was so cinematic.”

At first glance, this choice of words seems like a compliment. A little closer inspection, however, and it might start to seem odd to praise a piece of art for evoking another medium altogether. “Cinematic” seems benign, but sometimes it can be loaded with unintended subtext by indicating that we, as a culture, hold films in a higher regard than games, and thus use that word as a way to say “No, but seriously, this game is so good it’s almost like a movie,” as if a game being a game is not good enough. The impulse to heap praise on cinematic titles reflects our own view of games as they occupy space within a hierarchy of art: that is, we suggest that “cinematic” is the pinnacle of what a game should strive to be, and that somehow being just a game is inferior.

as if a game being a game is not good enough

This valuation of one form of art by the standards of another is strikingly reminiscent of a period in the early history of photography in which photographers emulated the conventions of painting in an effort to boost the reputation of their medium. These “painterly” photographs (which is a term that has direct correlation to the term “cinematic” as it describes games) are what legitimized photography as an art form, and helped break down the disdain with which the art establishment viewed photography.

As it turns out, new artistic mediums have a long history of borrowing from their more established cousins. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, photographers began creating images that they hoped could be exhibited as art. Up until that point, photography was regarded largely as a mechanical tool of documentation, a device that had utility, not one with means of artistic expression. How could something so automated create any kind of art that would rival painting or sculpture? Painters (and the art establishment at large) viewed photography as an inferior, juvenile, and talentless form of expression. Considering photography’s ubiquity today, this notion is laughably antiquated. After all, you’ve probably taken more selfies with your smartphone than you’ve painted self-portraits.

this notion is laughably antiquated

In the late 19th century, as a way to challenge the idea that photography could not create art, photographers began making images that borrowed from the conventions of painting and imbued the process of photography with a handmade aesthetic, appealing to the eyes of those who favored painting, hoping to borrow that legitimacy and bridge the gap between the two mediums. This movement, called Pictorialism, was practiced by a group of artists that exhibited at a gallery in New York called The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession. Alfred Stieglitz, a photographer and the owner of the gallery, also published a photography journal called Camera Work, which circulated the Pictorialist photography the Photo-Secession was creating as a means to promote photography as a fine art.

The photography made by the Photo-Secessionists was often dreamy and fuzzy in appearance, featuring softly lit and slightly out-of-focus landscapes that were charged with mood and atmosphere. The Pond—Moonrise, a photograph taken by Edward Steichen in 1904, a member of the Photo-Secession, is one of the clearest examples of how photography imitated painting in its early years. (One of the three prints of this image was purchased at an auction in 2006 for $2.9 million, which at the time broke the record for the most expensive auction price for a photograph.)

The Pond—Moonrise by Edward Steichen, 1904

The image looks, well, like a painting. Rather than capture the landscape with sharp accuracy, Steichen rendered the trees and light with a hazy appearance, which makes the scene look like something out of a dream. Additionally, the image appears to have large brushstrokes over its surface, a result of the application of light-sensitive materials that were literally painted onto the image’s surface during the development process, which is what causes the image to have color. Without the application of these materials, the image would have appeared in black-and-white. If a critic described this image at the time as being “painterly,” that would essentially be synonymous with “artistic” or “good.” Similarly, when a game like The Last of Us gets praised for being “cinematic,” that essentially means “good,” too.

In Camera Work, art critic Charles Caffin wrote that Steichen’s photograph “is in the penumbra, between the clear visibility of things and their total extinction in darkness, when the concreteness of appearances becomes merged in half-realized, half-baffled vision, that spirit seems to disengage itself from matter to envelop it with a mystery of soul-suggestion.” A bit lofty, sure, but incidentally, Caffin’s statement perfectly summarizes the state of the medium of photography itself at this time: a sort of half-realized, half-baffled vision that had yet to come fully into focus.

soaking in that shared legitimacy

That’s not to say that these Pictorialist images were not beautiful: they clearly are very successful attempts by early photographers to create art. But understanding why those images look the way they do and understanding what function they served in photography’s path towards acceptance is vital.

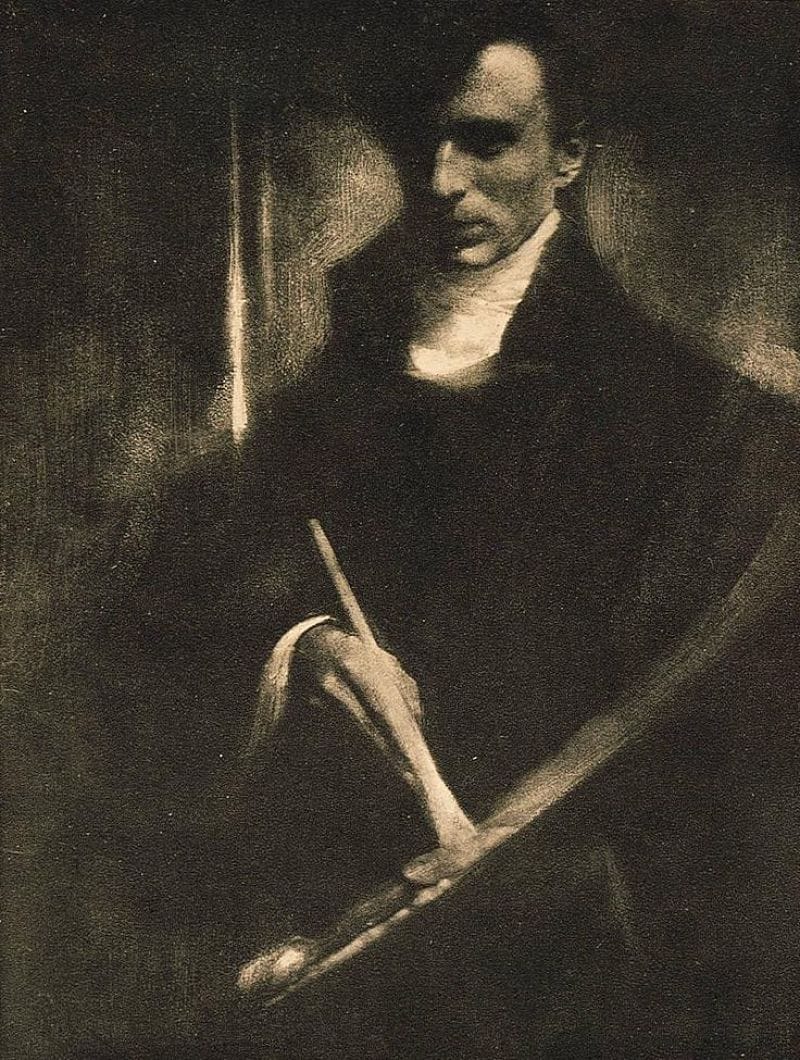

Steichen himself seemed to struggle with his own identity as an artist, portraying himself in a self-portrait from 1902 as a literal painter in which he holds a brush and palette rather than a camera and tripod. An interesting choice, given the image was actually taken by a camera, and is maybe a visual argument for the idea that though Steichen’s tools are different from painters, he still has the mind of an artist. Or perhaps this image serves to further convince the art world of the merit of photographers and show that they, too, can create compelling images with their medium that contribute to, rather than dilute, the art world.

Self-Portrait by Edward Steichen, 1901.

Regardless, Steichen and the other members of the Photo-Secession sought to make photography an acceptable medium in which to make art, and they did so by aligning themselves with the already accepted methods of art making, soaking in that shared legitimacy and using it to their advantage.

///

As photography began to establish a space of its own within the art world, Pictorialist images began to fall out of fashion; in the late 1920s, more modernist photography began to emerge. These new images sought to understand what made photography unique as a medium, to exploit those qualities, and to create images that no other medium could. This sudden desire to create images that would capitalize on the inherent strengths of the medium shook the painting world as well: since photographers could render reality with exact precision, why should painters even try to recreate landscapes or portraits of people? This question is what many believe to have sparked the more abstract painting movements like Impressionism, Expressionism, and Cubism.

to create images that no other medium could

The photography of the 1920s and 30s, rather than appearing hazy and dreamlike, has an intense focus on accuracy and image fidelity. These images, rather than imitate the conventions of painting, draw attention to their mechanical nature of production and exploit their inherent ties to physical space, which yield incredibly detailed studies of nature, people, machines, and our newly evolving industrialized landscapes.

It was during this time that photography really established its own space as a medium and found a visual language of its own. Rather than imitate the themes and ideas present in painting, photographers focused on the physical reality of things, whether through abstracting them and creating interesting compositions out of everyday objects, or inspecting them with intense scrutiny.

A number of photographers who practiced this new form of “straight photography,” a term referring to the artists’ dedication to not alter or manipulate their prints, formed a group called f/64. Even the name of the group itself, which is a reference to a setting on a camera’s aperture that yields images with intense sharpness, is a complete rejection of the fuzzy, hazy images created by the Pictorialists just a few years prior.

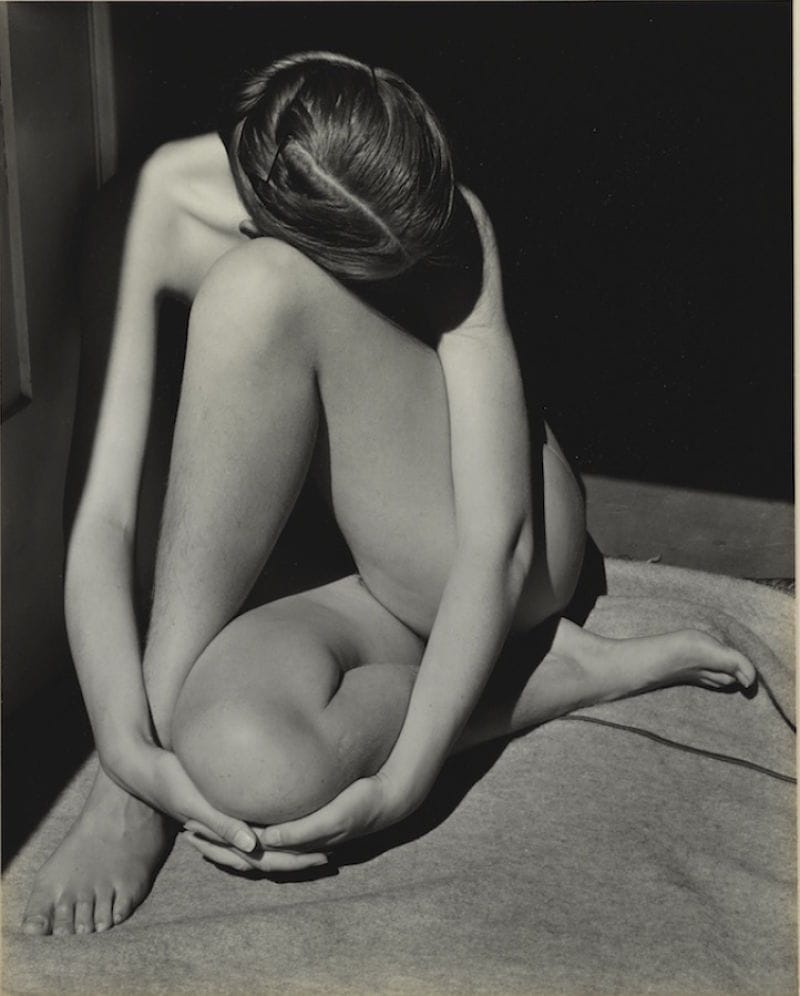

Charis, Santa Monica by Edward Weston, 1936.

Clearly, there is a history of this tendency for new mediums to imitate their predecessors as a way to meet the status quo. Therefore, from an art historical perspective, when a game is described as “cinematic,” I hear echoes from the history of photography. When that word is used, it becomes clear that as a medium, games are still struggling for respect.

Vice’s Ed Smith wrote, in an article entitled “They May Look Great, But Video Games Can Never be ‘Cinematic,’” that games often remind him of movies, but “not contemporary films—those are intelligent, well written and mature, everything games are not.” Here, Smith says that games (all of them, apparently) are immature, their writing is “shite,” filled with the “worst excesses of film—fanfare, distraction, [and] meaningless pageantry.” Smith makes a similar point to mine—that games emulate their closest cousin—but ironically, he says so in a way that plays into the pretensions and disdain with which the art establishment saw photography in the early 20th century. Rather than blast games for attempting to emulate film, we should realize that the imitation of an established medium, regardless of the perceived success with which this is done, is a vital step for any new medium to take as it carves its own space and earns the respect it deserves.

games are still struggling for respect

And when games do reach that level of acceptance, it will be interesting to see what the equivalent of “straight photography” will be in video games. Like with any new movement in art, innovation tends to start in the fringes and then work its way towards being the norm. Will game developers soon abandon the cinematic game and focus solely on the purity of their medium as photographers did? I hope not. Some of the most successful and interesting games of the last ten years are the most cinematic. Modern games by BioWare and CD Projekt Red feature conversations between characters shot exactly as if they were from a movie, making use of filmic conventions in order to facilitate the role-playing. Similarly, Tomb Raider and Uncharted games feature scenes of enormous scale, recalling something from Indiana Jones, but shot in claustrophobic, unbroken long-takes, like the award-winning work of Emmanuel Lubezki in Gravity. Nothing makes sense without any kind of context, and thus the borrowing of ideas and exchanges between mediums can make the best art. Moments like this prove that “cinematic” is just one of many things a game can be, and that “game-like” is perhaps an equally useful way of describing cinema.

Header image courtesy of U.S. Library of Congress.