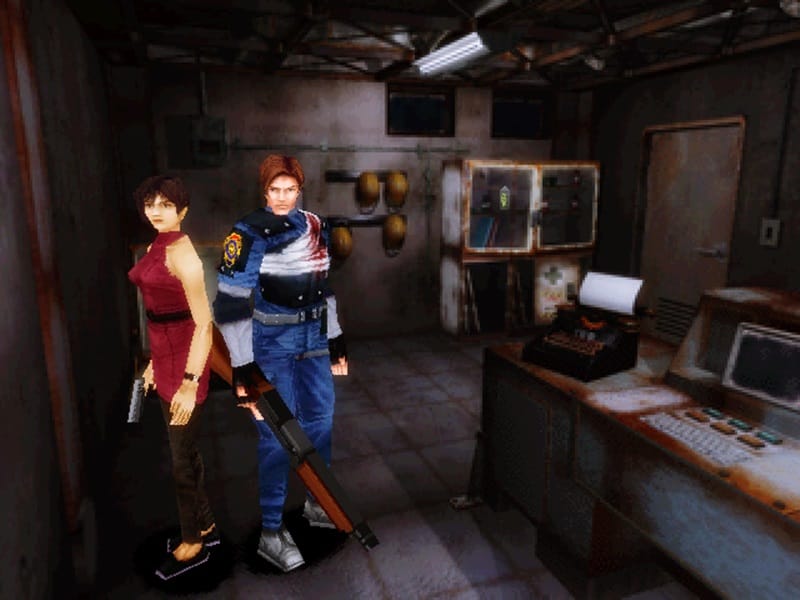

The horror of Resident Evil 2’s police station

There’s one tiny detail in Resident Evil 2 which illustrates, perfectly, what I love about the game. On the balcony overlooking the main hall is the operation switch for an emergency ladder, which the player can choose to activate. It creates a shortcut between the ground floor reception and the first floor, making it a lot easier and safer to travel back and forth carrying puzzle items. But why wasn’t it dropped already? Why is the player, arriving into the Raccoon Police Department long after zombies and monsters have breached the barricades, the one to drop the emergency ladder? Exploring the station, you learn that many cops and Raccoon citizens used it for shelter during the zombie outbreak, oftentimes holding out for days whilst trying to scrounge weapons and supplies. So why didn’t anyone open the shortcut before? Why didn’t anyone believe that being under attack by monsters and zombies constituted enough of an emergency to drop the emergency ladder?

Why didn’t anyone drop the emergency ladder?

The ladder is meant as something for the player to deliberate—if you drop it you can travel faster, but it might enable enemies to follow you between floors. It’s a mechanic, it’s a device. It’s a primitive, small example of choice-based design and branching narrative. “Do you want to play travelling the long way between the ground and first floors, or do you want to risk opening the shortcut?” That’s a very videogame question. But in Resident Evil 2 it’s rooted to a real-world object, to the context and confines of a fire escape inside a metropolitan police station. Ignoring boring questions about realism or plausibility, the game nevertheless does a fascinating job of tying videogame conceits to comprehensible mechanisms and architecture. You begin Resident Evil 2 on the streets of Raccoon, and it’s all bloody and urban and dire, and then you arrive at the police station and it becomes strange and abstract. It’s a building that you get—it’s a reference point to real life—but it’s filled with things that are odd and videogamey. Like that emergency ladder, which in real life would have been dropped by now, but hasn’t because it’s something for the player to toy with, Resident Evil 2, aesthetically and geographically, is a blend of credible and conceptual.

The main hall is far too big and seems to have no practical purpose, housing only a single reception desk, but like the lobby of the Spencer Estate in Resident Evil 1, it makes a great establishing shot of the building. Vast and empty, it leaves you feeling vulnerable, exposed and daunted—how the hell are you ever going to get out of a place this big, especially when you look so small? And it’s a terrific rug-pull. If you’re playing Resident Evil 2 for the first time, when you walk through the police station doors, you can’t possibly expect to find what you do, the massive ornate hall, occupied by the marble statue of the woman holding a jug.

Vast and empty, it leaves you feeling vulnerable, exposed and daunted

The east side of the first floor is the most plausible part of Raccoon’s police station. Here you’ll find an operations room (one of only three offices in the whole building to contain general desk space), an interrogation room and a press briefing room. The concentration of zombies is also much higher here than anywhere else in the building, the sense being that, unlike the library, STARS office and evidence room on the west side of the police station, this is where people would congregate. But it still has its abstractions. In the press room you have to solve a puzzle which involves lighting burners underneath paintings, in sequence, so as to unhook a golden cog wheel which is stuck inside another painting. And on the second floor of the east side, you have a gigantic room filled with battered old paintings, where you must insert two red gems so as to get a key from a statue, and Chief Irons’ office, the walls of which are covered with taxidermied animal heads. Resident Evil 2, unfortunately, pulls back a little here, and reveals through the found diary of a receptionist that the RPD building used to be an art museum. More interesting would have been to leave the various curios and oddities, the scattered statues and portraits, unexplained, to let real clash more violently with unreal and leave the player guessing and uncertain about their surroundings. Irons, though he’s not the stereotypical mad doctor or priest, puts a face and an explanation to the RPD building’s eccentricities—he brings the whole thing back down to the ground. It’s why I’d encourage people, especially if they’re playing as Claire, to explore the west side of the police station first.

There’s another operations room here, plus the evidence lockers, the dark room and the STARS office, but the west side also contains the library and the bell tower, rooms which above any others in the RPD building provide the sense of abstraction. The library in particular is completely out of place—like one of the impossible elevators or guest rooms inside The Shining‘s Overlook Hotel, it seems to have been lifted here from another building entirely. The huge portrait on the west wall, the moving shelves puzzle and Resident Evil 2‘s best jump scare, whereby the player falls loudly through the cracked wooden floor of the interior balcony, make the library a crystalline example of weird being made to seem normal, of strange things happening inside a recognizable location that itself, when you look at it with your head to the side, is also slightly strange.

Resident Evil 2 has to work to make a city’s police station into a weird, unsettling place

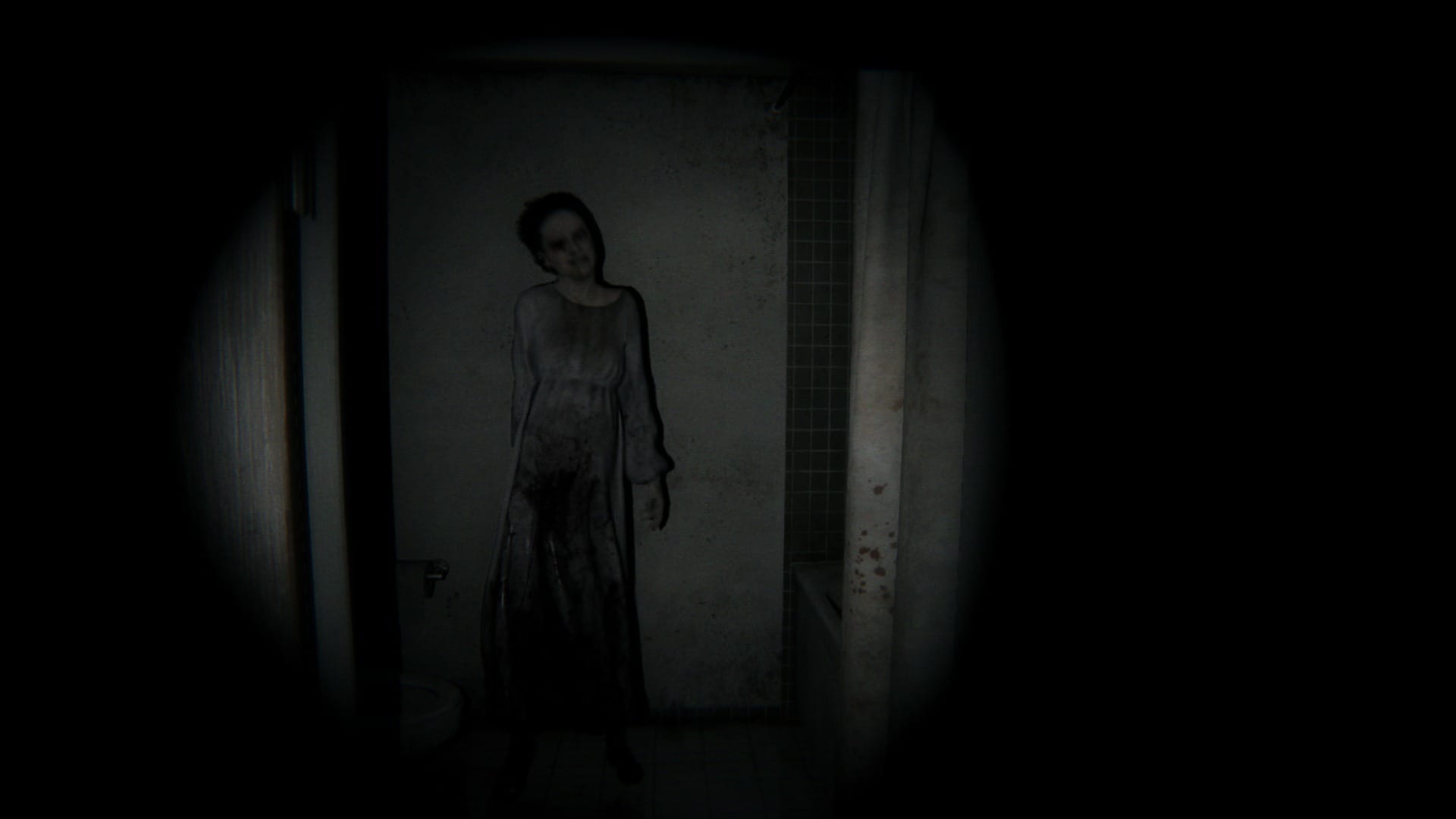

One of the reasons P.T. is frightening and Amnesia isn’t, or Outlast, is because P.T. takes a plausible location—the corridor of a suburban house—and contorts it. It’s a place you’re one day bound to walk through, and when you do that game might come to mind. On the other hand, you’re unlikely to visit a Baroque period German castle, or an insane asylum high in the mountains. And even if you do, the scariness is already there—we instinctively fear the dark, the dank, the idea of insanity or imprisonment. It’s easy. Resident Evil 2 has to work and effectuate to make a city’s police station into a weird, unsettling place. I love how it walks the tightrope, balancing between total a disregard for architectural consistency and a determination to set a horror game inside a municipal building. It falls apart during the latter section of the police station, when you enter the kennels, the morgue and the sewers, and Resident Evil 2 devolves into horror cliches, situating the player in traditionally scary dark confines and surrounding her with giant spiders. The underground of the police station is brute-force horror, so not horror at all—the lights are out, the monsters are everywhere and compared to the eerie music in the library, the soundtrack is pure foreboding gloom. But aboveground, the police station shines.

Like the emergency ladder, which should be down but isn’t, for the benefit of a more vibrant game experience, Resident Evil 2 with the RPD building weaves between grounded and absurd aesthetics. We often hear of the tension in games between realistic and unrealistic, a story you can care about versus mechanics that are exciting and fun. But Resident Evil 2, by pitting you against horror movie monsters and having you solve weird puzzles, in locations that are anatomically correct but tonally wrong, attempts at least to unify plausible fiction with inexplicable minute-to-minute mechanics. Grounded, “gritty” horror games are boring. I can see why the original version of Resident Evil 2, now dubbed Resident Evil 1.5, was discarded just before completion. If you look at it, either in surviving early demo footage or one of the sketchy rebuilds made by fans, the police station in that game is much closer to reality, encompassing metal shutters, a gun range and a lot more office space. It’s not as strange and expressionistic—the geography does nothing to wrongfoot you. But then wholly surreal, hypnagogic horror games, like The Evil Within, struggle with gravitas as well, and are too removed to be frightening—if everything is happening inside a dream world, what danger are you in? Between those two sensibilities, Resident Evil 2 is not always successful in finding a middle ground, sometimes too cautious, sometimes forgetting of itself, but in rooms like the police station main hall and the library you find a wonderful blend of real and unreal, a combination of ideas attempted by very few other games.