The House and the Labyrinth

George Trevor is perhaps the most unassuming character of Resident Evil’s long history. Among the series’ absurd cast of bio-engineered mercenaries and steroid pumped special forces agents he is little more than a whisper on the wind, a faded echo of a faceless man. His relative obscurity is for good reason: Shinji Mikami, Resident Evil’s lead designer, cut Trevor’s storyline as the original game neared its 1996 release, citing a lack of time to fully develop the story. Apart from a few notes published in a Japanese-only book on the making of the game, Trevor’s narrative only reappeared 5 years later, in the 2002 Gamecube remake. Expanded into a second story, with its own haunting boss fights and concealed passages, it was an important addition to the classic survival horror.

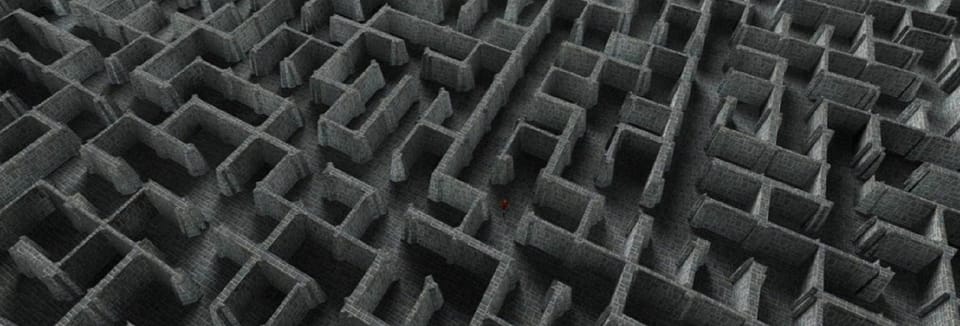

George Trevor’s importance lies in his role—he is the architect of the Spencer Mansion, that decaying piece of mock-victorian masonry on the outskirts of Raccoon City in which the entirety of Resident Evil is set. He is the man who orchestrated the mansion’s ornate puzzles, hidden passages and twisted corridors. In the fiction of the game, he is its designer, a cipher constructed to explain away why this so-called house is more like a maze, a dark labyrinth of yellowing wallpaper and dust-choked chandeliers. In a game where character confrontations are confined to passing exposition spaced liberally among hour upon hour of empty corridor stalking, Trevor is also the character with whom the player has the most significant, if indirect, interaction. His whimsical ground plan for the mansion is the ultimate object of mastery for the player—once it is mapped, understood and exploited, the game becomes distinctly easier. That is the duplicity of Resident Evil: the feeling of both observing the game’s ornate architecture and the experience of forging a path through it first hand.

///

Maze-treaders, whose vision ahead and behind is severely constricted and fragmented, suffer confusion, whereas maze-viewers who see the pattern whole, from above or in diagram, are dazzled by its complex artistry. What you see depends on where you stand, and thus, at one and the same time, labyrinths are single (there is one physical structure) and double: they simultaneously incorporate order and disorder, clarity and confusion, unity and multiplicity, artistry and chaos. They may be perceived as a path (a linear but circuitous path to a goal) or as a pattern (a complete symmetrical design) […] Our perception of labyrinths is thus intrinsically unstable: change your perspective and the labyrinth seems to change.

– Penelope Reed Doob, the Idea of the Labyrinth

///

The duplicity of Resident Evil’s design is the same duplicity as that of the labyrinth. To use Mary Reed Doob’s terms, the game casts the player as both “maze-viewer” and “maze-treader.” The Spencer Mansion is a maze you can plan a route through, room by room, from the confines of your map. In this phase the game offers order, clarity. But step outside of a safe room and confusion sets in, fear and disorder picking at your self-consciousness. This is a piece of architecture that satisfies as both path and pattern, but, as with any two-faced entity, the game’s labyrinth is not to be trusted.

The duplicity of Resident Evil’s design is the same duplicity as that of the labyrinth.

This is not a unique piece of game design: Metroid Prime and Castlevania: Symphony of the Night stand as highpoints of a similar experience. However, their settings are what differentiates them from Resident Evil. The cavernous science-fiction and fantasy worlds of both titles lean towards the spectacular, depicting grand halls and enticing vistas. Resident Evil locks the player firmly into a claustrophobic sense of domestic scale. A key in Metroid might open a whole mining complex; a key in Resident Evil often grants access to a single room, a few steps of space in which to explore. It is the Gamecube remake of the game that best captures this contrast, its detail-crammed interiors and twisted camera angles distorting the player’s perception of distance. What appears to be a simple square on the map is revealed to be a shadowy study, shelves crammed with artifacts, paintings setting dark landscapes into walls stained with unknown marks. The sheer volume of furniture and interior decoration explodes the game’s sense of space, imbuing every lamp and chintzy sofa with a unnerving presence. These mock Victorian furnishings are no accident—the Spencer Mansion’s interior decoration connects to a long tradition that stretches back through Psycho’s taxidermy and Terra Incognita’s “furnished rooms of nonexistence” all the way to Walter Benjamin’s examination of the bourgeois interior.

///

[M]agic prevails more covertly in the interior of the bourgeois dwelling. Chairs beside an entrance, photographs flanking a doorway, are fallen household deities, and the violence they must appease grips our hearts even today at each ringing of the doorbell. Try, though, to withstand the violence. Alone in an apartment, try not to bend to the insistent ringing.

– Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

///

Resident Evil’s setting is not simply a labyrinth for players to become lost in, it is also a house—and it is in that conflation of spaces that its horror lies. This territory was also recently explored by Hideo Kojima and Guillermo Del Toro’s P.T., an interactive demo released for upcoming horror game Silent Hills. In it, the player walks the same L-shaped domestic corridor hundreds of times, locked in a cycle that becomes increasingly distorted. Like Resident Evil, it locates its horror in a space of constant transition between house and labyrinth. Its opening image, that of two cockroaches connected back-to-back, is a clear symbol for the horror of its setting: the familiar, only repeated, twisted, made suddenly strange. Even the first radio broadcast to meet your ears charts this precarious balance, telling of a father murdering his daughter and wife without explanation: “This brutal killing took place while the family was gathered at home on a Sunday afternoon,” says the announcer, marking the moment where the normal became the terrifying, where the space of the house yawned wide and became the endless internal struggle of the labyrinth.

The family of George Trevor met an equally terrifying fate. It is his daughter Lisa who makes her presence most felt in Resident Evil’s Gamecube remake, transformed as she is into a howling indestructible monster, masked with the torn faces of her tormentors. Unlike the ornate double-crossing and corporate espionage of the games’ main storyline, the story of the Trevor family is tragically simple, and steeped in a kind of primal fear. Its addition is so important because it gives the Mansion an adopted family, one as twisted and filled with secrets as the building itself. That this family is Trevor’s, the architect, only further deepens the connection between the architecture and the narrative of the game, presenting a world where the game’s enemies could even be thought to be expressions of the Mansion’s perverse layout—like the Stanley Hotel in Kubrick’s The Shining.

///

Perhaps I will alter the whole thing. Kill both children. Murder is a better word. Chad scrambling to escape, almost making it to the front door where Karen waits, until a corner in the foyer suddenly leaps forward and hews the boy in half. At the same time Navidson, by the kitchen, reaches for Daisy, only to arrive a fraction of a second too late, his fingers finding air, his eyes scratching after Daisy as she falls to her death. Let both parents experience that. Let their narcissism find a new object to wither by. Douse them in infanticide. Drown them in blood.

– Mark Z Danielewski, House of Leaves

///

Symbolically, the house and the family are intrinsically linked in art. But if the family is what lives at the centre of the logical, symmetrical and conceivable space of the house, what is it that lives at the centre of the labyrinth? Mark Z. Danielewski’s book House of Leaves is perhaps the strongest study of this question. A work that is itself a maze of footnotes, appendices and transcripts, it is constructed around the story of a photographer, Will Navidson, who finds a door in his house leading to an endless set of dark and empty rooms. Told through an ornate construction of essays and narration, in its later parts the book fragments, breaking itself down into pages dominated by blank spaces as Navidson goes ever deeper into the house.

It is in that conflation of spaces that its horror lies.

The experience of reading House of Leaves is that of navigating a space much like the Spencer Mansion or the P.T. teaser’s fractured corridor. Notes are gathered, investigations made, and fear overcome as the irresistible descent into confusion and disorder continues page by page. By the time every page holds only a single broken sentence, each page turn becomes analogous to a step towards the heart of the labyrinth. What Navidson finds there is ambiguous, but House of Leaves does present the reader with many possible interpretations of the minotaur that lurks at the center of its maze.

George Trevor, searching for his family, also ends up lost in the maze of his own construction. It’s a fitting end for a man obsessed with the hidden and the ornate, a true believer in the magic of the bourgeois interior. After all, if the house is the home of the family, the location of logic and the space in which life passes, the labyrinth must be the home of senseless, meaningless death. Not an active, malicious force, but simply a process that exists in the absence of life and meaning. The 2002 Resident Evil remake’s strength lies in the plumbing of these depths and the loose articulation of their meaning. Few games have presented spaces of fear that so effectively explore how the domestic and the uncanny exist side by side with each other, and how the labyrinth itself presents a duplicity that entices and entrenches the explorer in equal measure.

George Trevor’s final words are a confirmation of that—the maker meeting himself at last, deep within the labyrinth:

“It was a dark and damp underground tunnel. And another dead end. But even in the darkness something caught my eye. Carefully, I lit the last match, I had to see what it was. A grave! But deeply engraved into the stone was my name! ‘George Trevor.’”