A videogame tribute to growing up around the Yugoslav Wars

Ivan Notaros appears in Issue 9 of Kill Screen’s print magazine. It launches on August 8th, but you can get 10 percent off before that date with the discount code RELAUNCH.

///

Ivan Notaros is constantly flooded with new game ideas. It’s the result of endlessly tinkering with videogame physics and art styles, letting his curiosity spill out onto his humming computer—each click of the mouse could result in another potential candidate. In my time speaking to him over the past few months for Issue 9 of Kill Screen‘s print magazine, he has released one game, dropped work on a larger one, started a collaborative project, and returned to another game that he started making two years ago.

The latter is the one that Notaros pitched to Stugan, the two-month program that brings a handful of game creators to the quiet Swedish woods to focus on building the game of their dreams. Notaros, and his game House of Flowers, were one of the pairs accepted into Stugan this year. And so, right now, and until August 27th, he’s miles away from the nearest town, batting away all the other game ideas that crowd his head to instead focus on this single one. Fortunately, it’s a game that means a lot to him. That should help.

{"@context":"http:\/\/schema.org\/","@id":"https:\/\/killscreen.com\/previously\/articles\/house-of-flowers\/#arve-youtube-8vn7bi7g4q8","type":"VideoObject","embedURL":"https:\/\/www.youtube-nocookie.com\/embed\/8vN7bI7G4q8?feature=oembed&iv_load_policy=3&modestbranding=1&rel=0&autohide=1&playsinline=0&autoplay=0"}

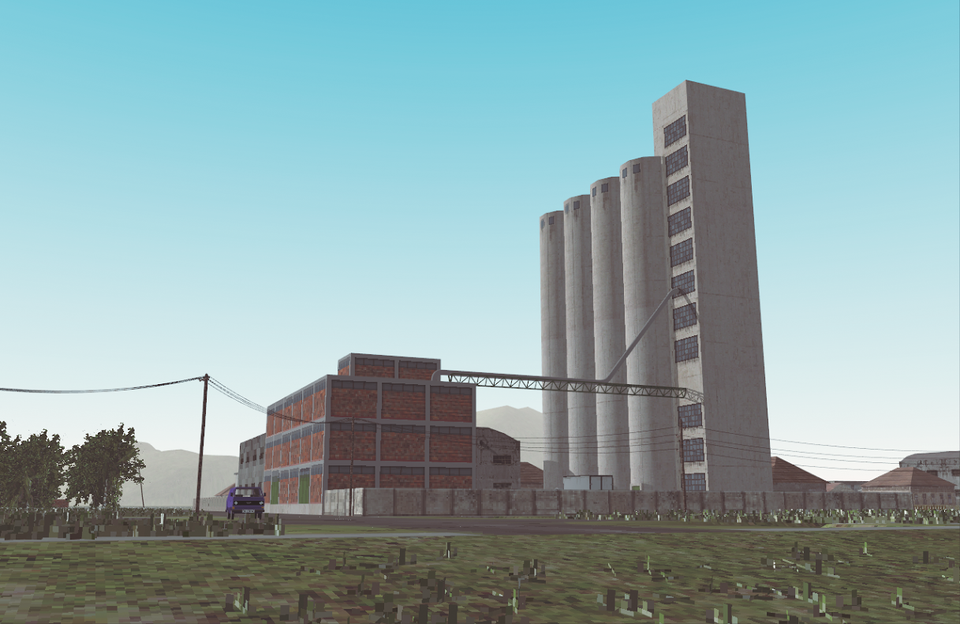

House of Flowers started out life as a low-poly, pixel art diorama of a truck on a road. Something about it struck Notaros as being quite Serbian. Being from Belgrade, Serbia himself, perhaps Notaros’s impression here isn’t too surprising. In any case, he stuck with this diorama a little longer, adding the ability to drive the truck, to walk around the scene, to carry things. It was mundane; practically a simulation of loading up a delivery truck. But in this dull normalcy, Notaros saw the potential to tell a story that he had personally become bored of repeating to the people he met.

“I think I always wanted to tell a story about the 90s in this region and the breakup of Yugoslavia,” Notaros told me. “Whenever I traveled, people kept asking me to retell what really happened in the wars, so I grew tired of repeating the same story. I mean, I was always explaining the war as something where everybody is guilty, where the core human values are the main factor of how things [turned] out, rather than a political entity or an officer or a powerful individual.”

Notaros grew up with these conflicts

The wars Notaros refers to are the Yugoslav Wars, which kicked off in 1991 and continued as a series of separate but related military conflicts until 2001. They were, in fact, the first European conflicts since World War II to be deemed genocidal in character, due to claims of ethnic cleansing between Albanians and Serbs. The result was the break up of Yugoslavia’s former republics, with Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Slovenia, and Serbia all becoming independent countries.

Notaros grew up with these conflicts, and also watched his parents deal with the difficulties they brought, including economic decline. His first-hand experience with the wars is what leads him to recount them from the perspective of a “normal person,” i.e. himself. He is close enough to the wars to know them in detail, but also distant enough to avoid pinning the blame for them on any individual person or group—his argument is that the cause is an issue that’s bigger than any single entity, it’s rooted in humanity itself.

Given that humanity’s darker side is Notaros’s focus, and this is something we can all understand, he is able to tell the story of what happened during his youth in a way that anyone can relate to, without the need for them to be familiar with Yugoslavian politics. That’s the potential he saw in that simple diorama with the truck. Interacting with the truck looked and felt Serbian to him while also being straightforward enough that anyone should be able to get what to do. With this as a starting point, Notaros started to build a bigger world around that central truck, one that would become a “love letter to [his] home.” As he says in his pitch to Stugan, House of Flowers isn’t so much a game about a war, but the effects of a war in the parts of a country where it didn’t directly take place.

The task in House of Flowers is to get by. You work with industrial machines as part of low-paying jobs that hurt more and more as the economic crisis worsens. Other aspects that Notaros saw during his childhood also play out, including: the decline of communist values, the rise of nationalism, the increase of crime and corruption, and the introduction of conscription. “The story is not a historical reenactment,” Notaros says in his Stugan pitch, “rather it’s the story of what led to the society I live in today.” That said, Notaros is taking directly from his own memories, picking out specific music, smells, sounds, and people that he recalls from the time and putting it all into the game.

House of Flowers is currently in development for PC. You can find Notaros’s games on itch.io.