How an artist turned Shadow of the Colossus into a rumination on chance

Game art tends to fall into two categories. On one hand you’ve got concept art and graphical assets used by developers to plan and build video games. On the other, you have nostalgic tribute art in the form of paintings, sculptures, and prints that fondly revise characters and game elements in an artist’s personal style. While both of these kinds of game art have their place in the world, they’re meant to appeal to gamer crowds, not your typical gallery hopper or art patron. The work of LA-based artist Oliver Payne meets artists and gamers somewhere in the middle. In a recent show at London’s Herald St gallery, Oliver Payne used video game footage to bring the medium into a more universally approachable light, one that doesn’t require having played certain games to understand what’s being said.

To approach Payne’s piece, simple, patient observation is all that’s required.

The focal point of Payne’s exhibition is an untitled video projection featuring two symmetrical arrangements of household items, including a pair of TV monitors with separate games of Shadow of the Colossus running on each. The rest of the duplicated objects are everyday domestic fare, including record players, incense burners, houseplants, oscillating fans, and stereo speakers. A chill, arrhythmic piano piece by experimental composer John Cage, appropriately titled “In A Landscape,” is heard in place of Shadow of the Colossus’ in-game audio. The incense burns, emitting thin wisps of smoke from time to time. The oscillating fans pivot in tandem, but gradually grow out of sync. The two Shadow of the Colossus players (never shown on screen) proceed toward the same goal of slaying the game’s first giant. There is no evidence of competition between the two, and instead, they each tackle the game at their own pace, employing slightly different strategies.

While viewers may need base level knowledge of how video games technically function (players use handheld controllers to direct on-screen avatars) to approach Payne’s piece, simple, patient observation is all that’s required. After all, the artwork is about systems in general, not just video games. Payne’s artwork examines systems such as how plants grow, the way record players spin at different RPMs, the varied results of assembly line manufacturing seen in the fans, and yes, the way people play video games too.

“I wanted to arrange the parameters in which a ‘thing’ could happen, but play no real part in the outcome. Everything ‘starts’ at once from an identical point and is left to behave ‘naturally’ in a highly controlled scenario.” Payne described this method as the work’s “Cage-ian element,” in that it draws from similar “chance aesthetics” as those employed by composer John Cage in many of his works. These chance-driven systems allow for a range of freedom and variable approaches, but are confined by the constraints of the systems’ designers. Games are balanced with this dynamic between player freedom and in-game boundaries in mind, allowing for a certain amount of player agency while also restricting the players’ choices to the rules of a their games’ worlds.

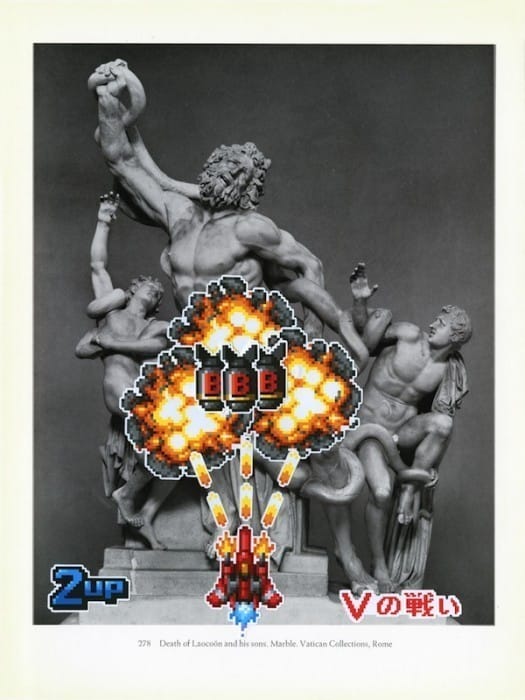

The Shadow of the Colossus video is not the first time Oliver Payne has used video games in his art. He’s juxtaposed sprites from bullet hell shooters on images of classic marble sculpture and composed field recordings of the near-extinct American arcade scene, as two examples. Though Payne has appropriated video game imagery for several bodies of work, he’d rather not be pigeonholed as a maker of game art. “I’m actually rather weary of using games in my work,” he says. “I see it as potentially dangerous. On the one hand, [videogames] are colorful, seductive and fashionable artifacts of low culture, but still, they offer ideas and invite dialogues that are fascinating and irresistible.” He points to Segagaga, a Sega-produced game that parodied the company’s failed Dreamcast console, as “a bizarre example of self-referential satire that could not exist in any other medium.”

Avoiding the perception that artwork featuring video games is only out to tug nostalgic heartstrings or express sub-cultural devotion is no easy task. There’s the risk that people who don’t play video games will immediately tune out, for fear that they won’t get any of the gaming references or see the relevance. Viewers who enjoy games can get hung up on the cultural validation of seeing gamer stuff in a public setting and stop investigating once they’ve identified all of the callbacks. “I’m not sure you can [avoid it],” Payne explained. “You just have to trust people to look deeper. It’s not about returning to childhood–simply that these subjects continue to be of interest to me.”

Plenty of video games could have fit the bill in Payne’s artwork, but he chose Shadow of the Colossus for its “epic minimalism.” “It’s absolutely huge yet nothing is really there,” Payne explained. “Shadow of the Colossus offers freedom without distraction, and is completely passive and meditative in this regard, much like taking an aimless stroll with no specific destination in mind. If you are not looking for the colossus, you are simply engaging in some form of flanerie.” Shadow of the Colossus is shown to be a sort of open-world game, but one that only has a singular objective instead of overwhelming players with the potential options.

“Shadow of the Colossus offers freedom without distraction, and is completely passive and meditative in this regard”

By installing two simultaneous games of Shadow of the Colossus side-by-side, Oliver Payne is showing viewers how the game both adheres to the narrow focus of its “story” and allows for a multitude of player experiences. While both players in the video approach the game’s first colossus at about the same time, upon attempting to climb the beast, one player is shaken off halfway up their climb, while the other has trouble gripping the fur around the colossus’ ankles. Both players ultimately take down the giant, but each has a different version of the story to tell.

As an interactive user experience, Shadow of the Colossus might be the most complex system in Oliver Payne’s installation, but the same variance in systemic processes is evident in all of the other objects as well. Why would one houseplant grow two leaves on one side and one on the other when the other houseplant does the opposite? Was it a matter of watering? Sunlight? Seed depth? And what then if all of those variables were identical?

It’s not that systems can’t be created that produce exact clones of a particular product, but Oliver Payne is showing how frequently the systems we perceive as offering identical experiences actually have a knack for uniqueness, even when the final outcomes are remarkably similar. At the end of the day, both incense sticks will have burnt down to stumps, but that doesn’t account for the diverse set of factors that might change the experience of incense burning as it occurs.

The result is an artwork that displays the plurality of experiences possible within seemingly duplicate systems. Payne’s work also presents the game Shadow of the Colossus in a way that doesn’t require prerequisite knowledge of the title or the technical dexterity to control the game on sight. For game enthusiasts, the artwork offers plenty of contemplative material to ponder about the nature of their favorite hobby without resorting to pandering. Payne’s exhibition could be read as a meta-commentary on designed experiences themselves. What is an art exhibition if not a system of chance aesthetics anyway? Show 100 people the same artwork, you get 100 different reactions and opinions.