Videogames and sports are kissing cousins and are part of the same family of life known as play. With the rise of eSports, the conversation about the ways that PC games can learn from the likes of football and baseball has renewed. Over the next few weeks, iQ by Intel and Kill Screen will explore how these worlds intersect, whether they know it or not.

Major League Baseball playoffs have started, but for a lot of people, the real baseball season is already over. The explosion in popularity of fantasy sports in the past decade exceeded anyone’s expectations. Estimates are poor, but the FSTA suggests that over 33.5 million people play fantasy sports in the US. There’s even a sitcom about it. Fantasy sports players are less about the beer-guzzling, body-painting, high-fiving sports fan stereotypes, and more into number-crunching, eyeglasses-pushing, and calculator-pounding. But how did we even get to this point? What strange mixture of cultural factors lead to the growth of a statistically focused sports meta-game?

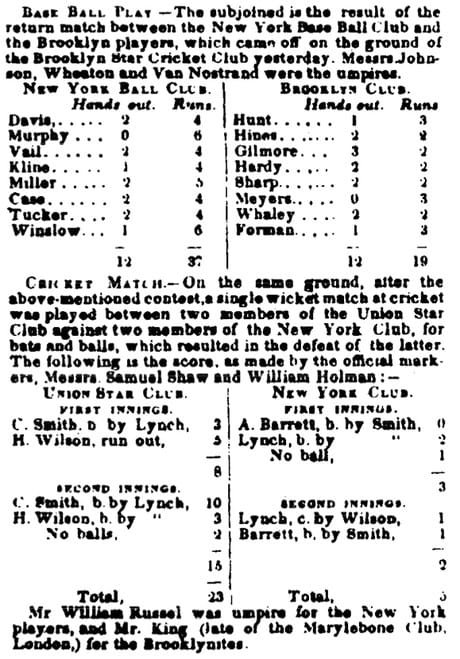

If we take a long view of media history, we can root this story somewhere in the rich history of the relationship between statistical analysis and sport, a history too long to track in any totality. On October 25, 1845, regular readers of the New York Herald would likely have seen something new, and perhaps unfamiliar on page three. Beneath the headline “Base Ball Play” was printed a short description of a game played between the New York Base Ball Club and an unnamed Brooklyn Team. But below that, divided into columns were a list of the last names of players on each team, and next to those were recorded the “Hands out” and “Runs” they contributed to the game. The columns of numbers were neatly tabulated, like an accountant’s ledger, and the sum at the bottom told the outcome of the game. The New York Club won by a score of 37 to 19.

This primitive data table from 1845 stands as one of the earliest extant examples of a baseball box score in an American print publication. There would be no fantasy baseball without it, or its antecedents. In the earliest fantasy baseball games, those that emerged before increased access to the Internet or even a personal computer, the scoring was tabulated by way of the daily newspaper box scores. Fantasy baseball was the ultimate paper and pencil role-playing game, except the role was part baseball manager, part certified personal accountant. The statistical emphasis of fantasy sports owes much to the specific data visualization of a baseball game.

Fantasy baseball was the ultimate paper and pencil role-playing game

Like many things in history, the birth of the box score — and the related emphasis on statistics in baseball — is the result of a mixture of cultural influences colliding at the same time. As the sport grew in popularity in urban areas throughout America in the mid to late 19th century, the country also experienced a renewed popular interest in quantitative analysis and statistics. In the later half of the century, social reform movements were inspired by an interest in numeracy, in the use of quantitative data to justify claims, and to influence policy change. Patricia Cohen, author of A Calculating People, writes, “By the mid-nineteenth century the prestige of quantification was in the ascendant…. Counting was an end in itself; it needed no further justification.”

It is in the incubator of American fascination with data that baseball comes of age, and that mixture undoubtedly influenced the sport by emphasizing its interpretation through data. The fervor for statistical analysis subsided in the 20th century, and more free-flowing ideologies took root, leading to the rise of jazz music, modern art, and performance art. But the effect on baseball persisted in the form of the box score, and the particular emphasis on numbers in analyzing the games.

Fast forward 160 years, and consider fantasy sports today. Once again, a curious mixture of cultural factors in the mid to late 90s influenced the game, and encouraged a growth in interest in fantasy baseball. Faster computers and Internet access allowed for asynchronous multiplayer fantasy play, a steroid-infused explosion of record-breaking resurrected the sport after the demoralizing morass of a prolonged players strike, and the expansion of 24-hour sports networks provided a constant drip-feed of data. The statistical heritage of fantasy sports, grounded a century earlier in larger cultural shifts, took a new life at the turn of the millennium.

Fantasy sports are now a global phenomenon, becoming increasingly popular across the world. They’ve grown as the market for them has been developed, and now have market share in the US alone estimated at billions, plural. Nothing spurs the growth of a pastime quite like its commodification.

This rapid growth in an arcane, statistical meta-game parallels a renewed modern interest in quantitative analysis that bears a striking resemblance to the cultural shifts of the late 19th century. Fewer of our American heroes are grizzled, burly men, known for the iron in their will and their biceps; they’ve been replaced by those who dominate the world through swiftness of keystroke, and through the cool calculations conducted behind their wireframe lenses. Exeunt Wayne, Jordan, Willis. Enter Jobs, Gates, Zuckerberg. The garage punk band has been replaced by the laptop DJ, the cigar-puffing oil tycoon by the hoodie-clad coder. Call it a geek revolution, or the Rise of the Geeks; however it might be labeled, it is certainly happening.

Sports have seen the same changes. Baseball sabermetricians, the statistically obsessed uber-geeks of the baseball world, have crawled out of their basement caves and into the front offices of the baseball. The granddaddy of them all, Bill James, works for the Red Sox as a special assistant. Each year for the past seven years MIT has hosted the Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, where owners, managers, and professionals from teams, media, and other sports industries discuss the increased influence of statistical analysis in sports. Always seeking an edge, professionals in sports are interested in discovering novel ways to read data, as the numbers are only as useful as their application suggests.

Exeunt Wayne, Jordan, Willis. Enter Jobs, Gates, Zuckerberg.

The parallel resurgence in quantitative analysis that birthed baseball in the late 19th century, and today’s renewed interest in big data and statistics in sports are strikingly similar, if not skewed by technological changes over the past century and a half. As I imagine, excitement around statistics thrived in the 1880s, so too today have terms like “big data” become buzz-words for many academics and professionals seeking to leverage the power of numeracy. But that similarity suggests an impermanence to the cultural paradigm, as the quantitative fervor of the 19th century gave way to other ideologies and influences, like the play of Dadaism, and the improvisation of jazz. Cultures shift like pendula, and we may yet see a swing back from quantitative supremacy in sports. The computers will get faster, and ever larger data sets will be organized and calculated with the swiftness of a Randy Johnson fastball.

But it may be that the future of fantasy sports as a game of numbers is not much of a future at all. The evolution of “fantasy” sport may be less about crunching numbers, and more about something else. For many fantasy sports players, the joy of the game is in finding new ways to engage in sports fandom. It encourages television viewership, has lead to scoring-play-only channels like the NFL Red Zone, and has spawned an entire cottage industry of strategy and prognostication websites. Maybe fantasy sports will move away from connecting fans to television, and will connect them to the increasingly popular interactive media forms of sport, like sports videogames.

Header image via Boston Public Library

David Ortiz image via Keith Allison